views

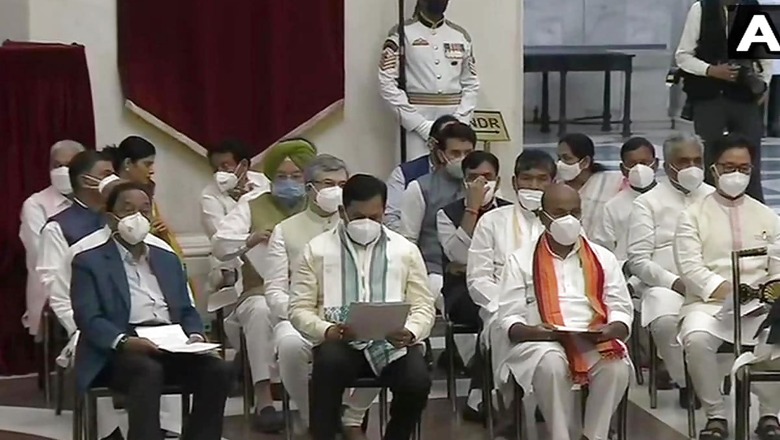

Narendra Modi’s first cabinet expansion or reorganisation in his second term as the Prime Minister was significant at multiple layers. An infusion of professionalism without inducting “lateral entrants”, ushering in the next generation of leadership in the BJP without subjecting the party to the throes that invariably follow attempts to bring in deep-seated changes in say, the Congress, making a half-hearted effort to reward the “performers” and penalise the “non-performers”, reaffirming the huge premium which Modi places on loyalty and trust and not the least, tailoring the exercise to suit the compulsions of electoral politics.

It was believed that Modi embarked on the cabinet expansion/shuffle from a position of vulnerability brought about by the poll reversal in West Bengal, the pandemic-wreaked devastation made worse by management glitches and a downbeat economy. However, the broad brush strokes, visible in the ouster of senior ministers such as Ravi Shankar Prasad, Prakash Javadekar (who also doubled as the government’s chief spokesperson in addition to being the Information and Broadcasting Minister), Harsh Vardhan and Santosh Gangwar, the downsizing of perceived heavyweights and the elevation of some ministers, suggest that the exercise was conducted from a position of unchallenged strength.

Big Changes at the Top

There was no doubt that after a bad year-and-a-half, Modi’s ministerial council needed a lick of varnish. That “talent” and “efficiency” were required right at the top was signalled in the induction of Ashwini Vaishnaw, a former bureaucrat who had served in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s PMO and was best known for acting as a bridge between the BJP and Naveen Patnaik’s Biju Janata Dal (BJD). Vaishnaw was from the Odisha IAS cadre and will be in charge of two big-ticket ministries, Railways and Information and Technology and Communications. Railways was held by Piyush Goyal and IT and Communications by Ravi Shankar Prasad.

Hardeep Puri was not only promoted as a cabinet minister, he got the Petroleum and Natural Gas Ministry in addition to Housing and Urban Affairs—clearly a recognition of the unwavering defence he put up for the Central Vista, a project that provoked flak from several quarters. Equally, Javadekar’s exit showed he was possibly not up to scratch in portraying the government in the “right” light when it was under siege. It is likely that with a slew of state elections and the battle of 2024, Prasad and Goyal will be involved more deeply in the BJP organisation.

ALSO READ | Big and Bold: The Narendra Modi Cabinet Reshuffle Ticks All the Right Boxes

That was the message from the changes carried out in the upper rung of the ministerial hierarchy. The significant social signals were beamed from the inductions lower down the scale, factoring in the pressing demands coming from the Assembly elections from here on as well as the general election. These were evident in the importance accorded to Uttar Pradesh—the centrepiece of the next battle—Uttarakhand and Manipur, to a lesser extent, while Punjab didn’t figure in the BJP’s political schema. The last is an admission of the BJP’s inability to be a significant player in Punjab, having lost its ally, the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD).

Therefore, the endeavour proves the care and thought that went into the additions and deletions, reinforcing a perception that Modi has little patience with making electoral investments that will not bring potential dividends. UP and Uttarakhand must be retained at all costs, the creases in Gujarat have to be straightened out while stability in Karnataka, the BJP’s only stronghold in the south, cannot be bartered away to keep chief minister B.S. Yediyurappa’s permanent baiters happy.

The UP Caste Matrix

In UP, that saw seven inductions, the BJP conceded that despite its seeming invincibility, it could not wish away its allies and the votes they brought to the table. Therefore, Anupriya Patel who heads the Apna Dal (Sonelal) was brought in, despite being passed over in 2019. An MP from Mirzapur in east UP, Anupriya represents the backward caste Kurmis, who make up the “creamy layer” of the socially and economically empowered backward castes with the Yadavs and Lodh-Rajputs.

Unlike Bihar, where Kurmis have remained with the Janata Dal (United) primarily because of Nitish Kumar’s leadership, in UP their votes tend to shift between the four major players, including the Congress, which netted most of the Kurmi votes in the 2009 Lok Sabha polls. Since 2014, the Kurmis rooted for the BJP but there’s no gainsaying that the allegiance is fixed. The Kurmi imperative also explains why Pankaj Chaudhary, Maharajganj MP, found a place in the ministerial council.

However, Santosh Gangwar, also a Kurmi and one of the BJP’s most successful MPs who won his seat multiple times from Bareilly, was dropped. What explains the move, especially since the BJP has not nurtured another Kurmi leader from Rohilkhand, a Muslim-strong region where the Samajwadi Party (SP) has a significant presence? The inference within the BJP was Gangwar publicly displayed his anger with the UP government for exacerbating the pandemic crisis in a letter.

That still does not explain how another MP, Kaushal Kishore of Mohan Lalganj, was accommodated. Kishore, a former CPI member, was the first to speak out against the state government during the health crisis. Kishore is a Dalit Passi known for his activism on ground zero. His induction is an outcome of the BJP’s strategy to knit together the Dalit sub-castes to counter the BSP’s following among the dominant Jatavs. However, like the Kurmi votes, the Passis too have no permanent loyalties and often tend to vote a caste candidate rather than a party.

The appointment of a Brahmin from north-central UP, two Kurmis from Poorvanchal, a Lodh from Rohilkhand, a Koeri from Bundelkhand, a Passi from Awadh and a Gaderia-Dangar from Braj, marks one of the most concerted efforts by the BJP to fit the splintered caste pieces into a complex mosaic making up the social fabric.

Looking Beyond UP

In Gujarat, which polls in November-December 2022, the BJP attempted a balancing act. Two Patels, Parshottam Rupala and Mansukh Mandavia, were upgraded to cabinet rank, ostensibly to quell the demand for projecting a Patel as the CM candidate—a clamour that never pleased the BJP brass. Three backward caste MPs Devusinh Chauhan, Darshana Jardosh and Mahendra Munjpara were made ministers.

Since the 2012 elections, when the BJP’s Patel base (consolidated since the 1995 elections that saw Keshubhai Patel emerge as the leader) looked uncertain, Modi resorted to a tactic of regrouping Gujarat’s huge but unacknowledged OBC base. He succeeded and in that election as well as the following one, the OBCs steadied the BJP’s ship.

ALSO READ | Cabinet Reshuffle Positions Narendra Modi as Champion of OBCs, Right before Crucial Polls

Keeping 2024 in mind and the need to possibly expand its base beyond the catchment areas of the north and west, the BJP brought in as many as four MPs from West Bengal. The Bengal bounty reflects the BJP’s doggedness to hold on to the gains made in the Assembly elections and not lose the advantage accrued in the last Lok Sabha polls.

Odisha—billed as a sunrise state for the BJP—found representation in the form of Ashwini Vaishnaw (although a Rajya Sabha MP) and Bishweswar Tudu (MoS in Ministry of Tribal Affairs and Jal Shakti). However, Dharmendra Pradhan, the BJP’s best known leader from Odisha, was moved from investment-heavy Petroleum to Education. Does it mean a concession to Naveen Patnaik’s grip over the state and the BJP’s inability to break in?

Likewise, barring Karnataka, the south remains a challenge although G. Kishan Reddy, its Telangana leader and MP, was promoted to cabinet rank and given the culture, tourism and north-east region development portfolios that will be monitored by the PM. In conclusion, Modi and the BJP effected a few prospectively far-reaching changes but the real test of their efficacy will be seen in the impending elections.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment