views

Washington: No one likes to own up to a coup. It’s usually nasty business and it can bring frowns and punishment from abroad (even when nations might be rooting for the coup leaders).

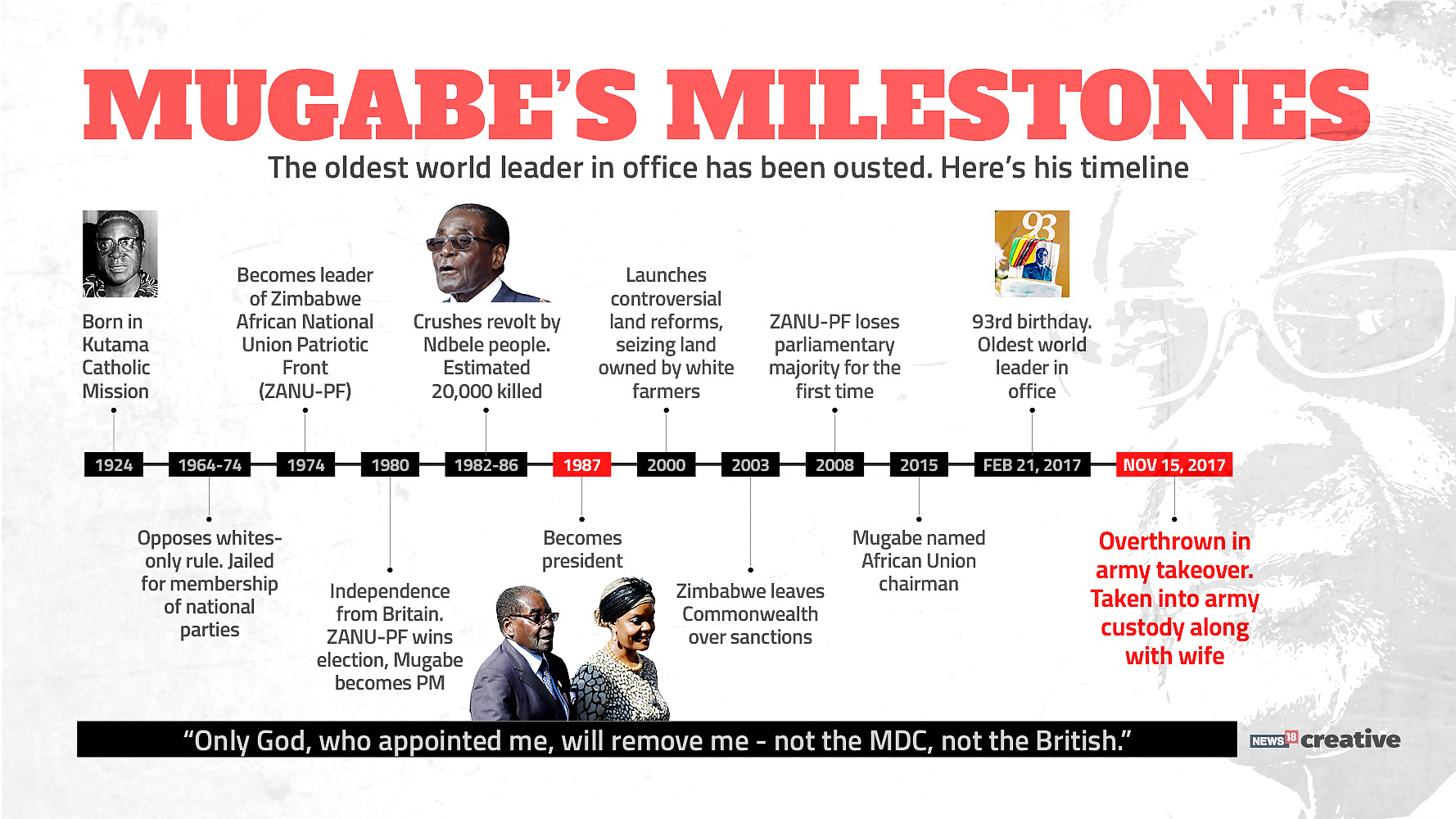

So it was this week as Zimbabwe's military forces placed President Robert Mugabe and his wife under house arrest and sent armored personnel carriers into the capital to cement control, all in service of what the army's supporters called a "bloodless correction."

A correction, not a coup? It may be too early to tell. But terms of art and squishy euphemisms are the norm in world affairs because words matter on that stage. They can mask the reality on the ground.

To recognize a "genocide" is to be expected to take consequential action to aid victims and bring perpetrators to justice. Like genocide, a "crime against humanity" is a crime under international law.

The Trump administration has edged up to a determination that Myanmar's brutal crackdown on Rohingya Muslims is "ethnic cleansing," but so far stopped short.

The United States uses rhetorical dodges to describe its own doings. It acknowledged using "enhanced interrogation," not the forbidden "torture" even if the difference was not apparent to those who were waterboarded before such tactics were banned.

It made infamous the much-disdained "collateral damage" label to describe the unintended bombing deaths of civilians.

And it hasn't technically been at "war" since President Franklin Roosevelt waged it against Japan, Germany and others in the 1940s, which has not stopped the U.S. from sending hundreds of thousands to fight from Korea to Vietnam to Iraq to Afghanistan in "extended military engagements," ''targeted actions" or the like.

Washington has struggled in addressing military takeovers before. In 2013, when Egypt's military ousted the nation's popularly elected Islamist president, the Obama administration debated for three weeks on whether to call the event a coup. It devised a novel solution: a decision that saying nothing best served America's national interests.

Within the State Department on Wednesday, the message about Zimbabwe was caution, with any declaration of a military coup potentially triggering a cutoff of U.S. aid to that country. Given Zimbabwe's murkiness, officials within the agency were strongly advised to avoid any talk of a "coup" or "attempted coup" until the situation stabilizes and an analysis could be conducted.

Zimbabwe's military leaders have not said whether they intend to replace Mugabe with another strongman, restore his presidency under an altered political landscape or transition to democracy. One motive was apparent: preventing Mugabe's wife, Grace Mugabe, from succeeding her 93-year-old husband, who has reigned for 37 years.

Whichever the case, it smells like a coup attempt, according to a widely accepted definition by U.S. scholars Jonathan M. Powell (now University of Central Florida) and Clayton L. Thyne (University of Kentucky): "Illegal and overt attempts by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting executive."

If what went down in Harare is acknowledged as a coup, however, Zimbabwe would face African Union sanctions and risk the loss of foreign aid.

A statement read by Maj. Gen. Sibusiso Moyo asserted that the action was only meant to target "criminals around" Mugabe. "We wish to make it abundantly clear that this is not a military takeover," said the statement, read as troops seized strategic points, the U.S. Embassy in Harare warned Americans in the capital to shelter in place and nothing was clear at all.

Comments

0 comment