views

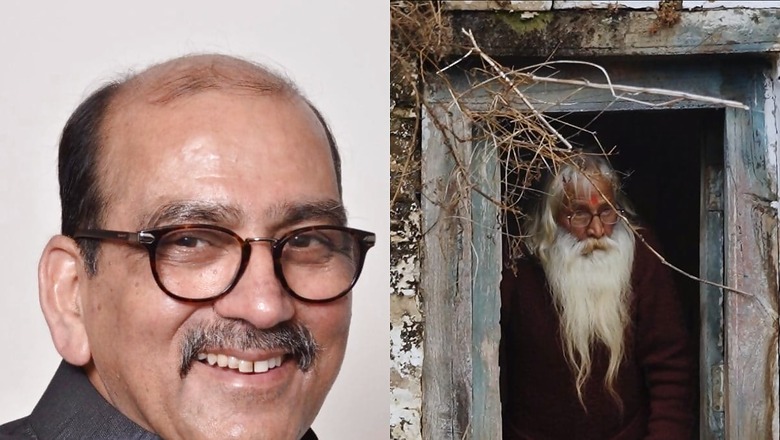

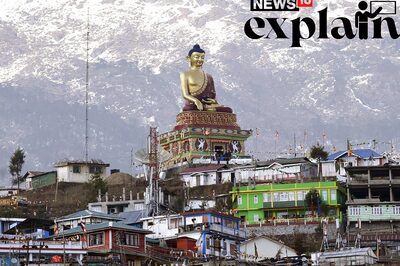

Film historian, documentary filmmaker, critic, former BBC journalist and founder-director of South Asian Cinema Foundation, Lalit Mohan Joshi recently added a new feather to his hat as he helmed a documentary film titled Angwal, which translates to ‘embrace’. The semi-autobiographical piece finds him returning to his birthplace in the Himalayas to explore the tradition of Kumaoni poetry and pay an ode to Kumaoni heritage, culture and literature. Combining the spoken word with music that typifies the region, the film captures the responses and deep philosophical worldview of some representative poets in the face of a society undergoing profound change.

“Not just the country, but also Kumaon needs to know of their poetry and art, and that was also a motivation of making it to a great extent,” says Joshi, who has made seminal documentaries including Beyond Partition (2006), Niranjan Pal: A Forgotten Legend (2011) and East Meets West: Indo-British Cinematic Encounters (2015). In an exclusive interaction with News18, Joshi opens up on weaving Angwal, paying a homage to his roots, the premiere of the film at the British Film Institute and the state of documentary filmmaking in India. Excerpts:

Could you take us a little through how you came across the idea of Angwal and how it came into being?

I’ve been living in the UK since 1988. I came here as a correspondent and radio broadcaster in the BBC Hindi service. Hills are always at the back of my mind because I was at my ancestral house in Naukuchiatal till I was seven although I was educated in Lucknow and Allahabad. Two of my maternal uncles were iconic Kumaoni poets, Shyamacharandutt Pant and Ramdutt Pant. Since 2017, I’ve been suddenly feeling like looking into it all over again. That was the inspiration behind the film. But I wasn’t sure at that time about what my film is going to be about. I thought of maybe exploring my own family and their Kumaoni poetry roots. That would be a prelude and then I thought, why not tell a story of Kumaoni poetry itself and the beauty of Kumaon, which is the inspiration behind the poetry. So, that was the basic idea.

When did you start shooting for the film?

We shot this film in 2019. I started tangibly thinking about it in 2018. In 2019, we shot for about a month in Shiloti, Malonj and Nainital. I was determined to make it within one-and-a-half years but then Covid happened. So, for the next two-and-a-half years, everything came to a standstill. During those days of depression, I started thinking if I’ll ever be able to complete the film. But I got into it again one-and-a-half years back. We shot some of the burans and the beds of flowers. We put everything together. Last year, I went to Haldwani and Nainital because I wanted to use the local talent. It became like a challenge to tell the story of poetry through cinema. So, I thought of picking some iconic poetry pieces and turn them into songs.

Could you let us in a little more about the music of the film?

I engaged Chandra Shekhar Tiwari and Harish Pant, who were my friends since I was in Lucknow. I had written a Kumaoni play at that time. I didn’t request but told them that they will have to compose the music for the film. I paid everyone but that wasn’t the payment people expect from a film. The film is a result of the love for the subject and I’m very grateful to everyone who collaborated and they were mostly Kumaonis.

Documentary films, even today, face a financial challenge. Most of them are made on a shoe-string budget and that’s also why many don’t even see the light of day. What are your thoughts on it?

Absolutely! You’ve touched the core of the dichotomy. When you want to make a film, you can imagine great things but when you’ve to actually make it, it needs money. The moment you bring in a camera, the money starts rolling. I’ve made four to five documentaries and I know the pain of making one. If you’re making a feature film, it can attract some people because they can think about making money. The lack of money while making a documentary throws a challenge at you. I spent a lot of money in this film and it was my own money. But that also makes you more imaginative. When you’re pushed into a corner, you end up thinking in a very innovative way and then what comes out is sometimes better than if you did it with a lot of money. In my personal opinion, if you’re determined to make something, you can. I know that I’ve some kind of reputation and credibility but if I had to make Angwal twenty years back, I don’t think I would’ve been able to make it with the kind of quality that I’ve made now. So, yes, money is a big thing.

So, how do you think this change can happen wherein documentaries receive a bigger spotlight?

In a country like India, we’ve a lot of talent. And we need to be compassionate and magnanimous in funding people. The kind of music I’ve in Angwal and the kind of feedback people have given isn’t completely my own credit. It’s a combined effort that has made the film so poignant that Prof Charles Drazin gave such an emotional review. I think he was more emotional than objective in assessing the film.

And what has the general response been so far?

The feedback has been very positive. A lot of people who watched it felt very emotional. I’ll tell you something unbelievable. I showed the film when it was nearly finished to those who were involved in the filmmaking at a degree college in Haldwani just to test the waters. The granddaughter of Shyamacharandutt Pant was uncontrollably crying throughout the film, so much so that she became a kind of spectacle. Some hard-core bureaucrats who were Kumaonis were very, very emotional. I think there was a sense of guilt in people’s hearts about how we’ve neglected our heritage and literature. For instance, in Bengal, there may be poverty but there’s a lot of respect for the arts. That’s why they’ve produced (Satyajit) Ray and (Ritwik) Ghatak. But coming back to Kumaon, I think my film really touches something that people like. Some people may think that Angwal is too analytical. It’s a personal story and is semi-autobiographical but also analyses the great poets of Kumaon and what differentiates Kumaoni poetry from Urdu shayaari and Bengali poems.

Go on…

Kumaoni poetry is unique because it’s composed around social issues. Some of our most touching poems are themed on migration and of people leaving. Many villages in Kumaon are ghost villages. So, yes, I think people have liked the film so far. It’s very encouraging and you don’t really need anything else if you’ve people saying that your work is good. It’s more important than money or anything else that you can get.

Angwal is being premiered at the British Film Institute, London on August 7…

It’s an honour for me. It’s very difficult for our films to be picked up by the British Film Institute, which is a mecca for film screenings. It’s being premiered at 11 am. I’m inviting some film critics and people who love cinema. I’m quite nervous about how they’re going to react to my film.

Comments

0 comment