views

The twelfth edition of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Ministerial Conference (MC-12) will take place in Geneva starting June 12. While the 164-member organisation was formed with much fanfare in1995, it is now seen as an underperformer in the pantheon of international organisations tasked to uphold the rules-based order. One fundamental problem for the WTO is that the rules-based order itself is under pressure.

Formed at the peak of globalisation, when the romanticism of post-Soviet ‘end of history’ was popular, the organisation has proved to be too rigid. The growing aspirations of rising powers like India and others are misaligned with the rules written in a unipolar world, and hesitant to accept these rules as the north star.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the Agreement on Agriculture. After the Uruguay round of negotiations which lasted eight years, several agreements were signed before the WTO came into force onJanuary1, 1995. One of these was the Agreement of Agriculture, at the time among the most important pillars of the WTO. The Agreement on Agriculture disadvantaged India in significant and permanent ways. It was designed to facilitate global trade flows for crop-surplus countries. But it failed to address the needs of countries with agriculture output variability, and worse, tied their hands in what they could do in the future to enhance domestic support for farming.

While tomes can be written on the issues with the WTO Agreement on Agriculture, and scholars like French economist Franck Galtier have elaborated on how to address the specific aspect of addressing public stockholding programs within the WTO architecture, there are three key related problems for India.

First, the agreement slotted subsidies in three categories – green (non-distorting), blue (minimal distortion) and amber (trade distorting), with the amber ones subject to a limit of 10% of the total agricultural production. Conveniently, the Agreement parked most of the developed nation subsidies under green or blue classifications, while developing countries were largely under amber, thus becoming subject to strict reductions and hard caps.

Second, the permissible subsidy dubbed the Aggregate Measure of Support is calculated based on the External Reference Prices of 1986-1988 — inflation is not accounted for. India’s position is that subsidy can only be calculated against actual procurement, which is contested by the developed countries. They insist that the Indian subsidy be calculated for the entire produce of a crop so long as it is under a Minimum Support Price regime, irrespective of the actual quantity of government procurement.

Third, while there is a “peace clause” for building public stockholding where India cannot be dragged to a dispute in case the subsidy for crops identified for food security exceeds the permissible limit, this is not enshrined in the Agreement. This “concession” was granted to the developing countries in return for implementing the Trade Facilitation Agreement, which came into force in 2017.

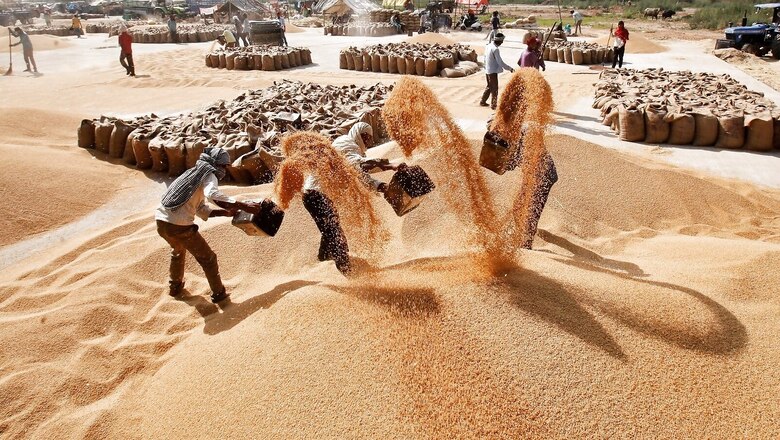

All these anomalies are evidently lopsided and blatantly skewed. A natural question that arises is why India signed up for this kind of a deal. One potential answer is that the policymakers and politicians who participated in the Uruguay Round between 1986 and 1994 did not have the foresight to see India emerge as a country that will one day transition to surpluses. Perhaps their assessment of Indian aspirations and capabilities was very limited. They never envisaged that India will one day want our ‘annadatas’ to export and prosper, and that one day, the government will be able to provision food to 800 million people for nearly two years, like India has successfully done through the global pandemic.

These are the anomalies India today seeks to correct in Geneva, as MC-12 approaches. The Indian proposal made to the WTO General Council along with G-33 – a loose WTO coalition which has 47 members, including the African Group and the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries – seeks to address these long-festering issues. The proposal is a bold counter-push against entrenched inequities.

Members representing more than half of the world’s population have asked WTO to grant them a fair and sustainable solution for the issue of public stockholding for food security purposes. Every developing country should be freely allowed to buy any quantity of any crop through any domestic mechanism to build buffer stock for food security.

The proposal envisages a more logical basis for calculating price support for public stockholding, fixing the reference price using prevailing market prices or proposing an inflation-adjusted calculation mechanism. This provision aims to ensure that even in the future, developed countries should not revisit the permanent entitlement of public stockholding under the pretext that such subsidised purchases had become very high and were thus trade-distorting.

The proposal also calls for allowing members to export from their public stocks for the purposes of international food aid, for non-commercial humanitarian purposes and for bilateral food diplomacy. This is a key limitation of the present Agreement and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has spoken of WTO building in such flexibilities in recent months.

In addition, India is opposing a carte blanche to the World Food Program to procure food-grains even if there are export restrictions in place. India has taken the stance that Indian policies have never hampered the work of the World Food Program and when export restrictions are applied, only a sovereign decision should create exceptions borne exclusively out of foreign policy considerations.

The developed countries on the other hand want to reopen the Agreement on Agriculture but to demand even more “subsidy discipline”. They wish to further cut subsidies being provided to this sector by the developing countries like India. This kind of manoeuvring is a classic modus operandi of the developed world – first they use the head start they have in a sector to create market monopolies, and then follow through by erecting regulatory moats in the name of rules-based order.

Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal is expected to attend the MC-12 event. Several of his illustrious predecessors from the yesteryears have been bamboozled under international pressure. At MC-12, India conversely seeks to reverse the horrors of history.

Whether the developing countries prevails in this negotiation remains to be seen – but this is the first time since the formation of the WTO that India is leading an offensive agenda on agriculture. At stake is not just India’s food security but also the potential to become a substantial food exporter, with exports of $50 billion already in sight.

Rajeev Mantri is co-founder of public policy think tank, the India Enterprise Council. Views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment