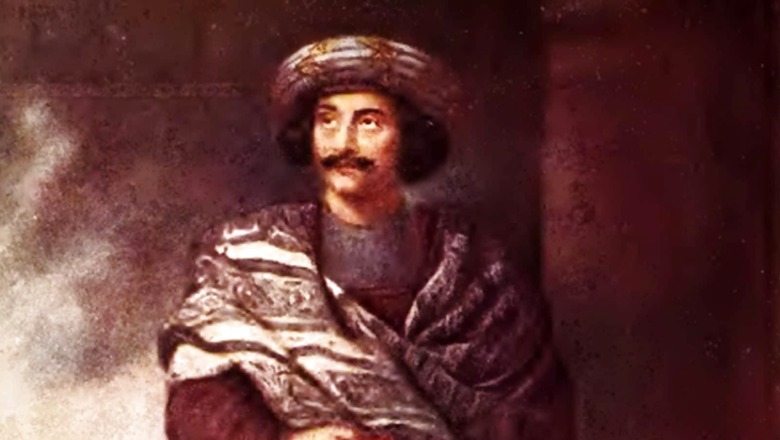

Past Forward: How Rammohun Roy Has Been Demonised Through Misinformation to Create a False Narrative

views

Our past can inform our choices in the future. Indian history is rich and diverse but we are used to reading it through colonial glasses. Past Forward will look at Indian history with a fresh perspective.

A significant number of responses to my previous article in this column acted as an eye-opener to me. The dominant theme of these reactions was that Rammohun Roy was a stooge of the British and the Christian missionaries. These allegations are not new: they were sensationalised by some celebrities and influencers of the right wing a couple of years ago. What caught my attention was the extent to which these silly allegations have been assimilated through social media.

Instead of going into a detailed rebuttal of all the allegations, for which this column is not the place, I will demonstrate through a few instances how information has been cherry-picked and distorted to force fit into a narrative of perceived grievance. Another aspect of this narrative that compounds the problem is a lack of understanding of the Bengal renaissance or a complete denial of it.

Roy is vilified for being an employee of the East India Company (by extension for not wanting to get rid of the British rule) for being a close collaborator of the Christian missionaries and even converting to the Unitarian church for ‘de-sanskritisation of education’, and for being a traitor who ‘diluted Hinduism’. It is alleged Roy was a sycophantic ‘brown sahib’ who was in turn promoted by the evangelical and colonial authorities as a prized catch. His advocacy for abolition of the Sati is shown as a prime example because, it is argued, the practice of Sati was nothing but a product of conspiratorial imagination of the Christian missionaries.

Let me start by clearing the misinformation that seeks to portray Roy as a life-long employee of the East India Company. In fact, Roy worked for the Company for a short time and intermittently in various capacities. These employments occurred between 1803 and 1814 when he moved to Calcutta. Thereafter, he was on his own. While much is made about Roy being given the title Raja, it is important to note that the title (which was bestowed upon him by the Mughal emperor) was not acknowledged by the Company.

A letter written by Roy in 1823 to the then Governor General Lord Amherst in which he argued in favour of a European education system is often produced to support the allegation that he was responsible for ‘de-sanskritisation’ of the Indian education system. The General Committee of Public Instruction, however, refused to act upon his letter on the ground that it expressed the views of one individual “whose opinions are well-known to be hostile to those entertained by almost all his countrymen”. The importance of Roy’s views, although appreciated by William Bentinck and Macaulay in 1935, was acknowledged officially nearly 60 years later when the Education Commission appointed by Lord Ripon noted in its 1882 report that “It took twelve years of controversy, the advocacy of Macaulay, and the decisive action of a new Governor General, before the Committee could, as a body, acquiesce in the policy urged by him [Rammohun].”

What is conveniently ignored is the fact that it was not Rammohun alone who advocated an English education system. Historian RC Majumdar noted in his Glimpses of Bengal in the Nineteenth Century that “Equally erroneous is the general belief that Rammohan Roy was the pioneer of English education and founder of the Hindu College”. He observed that long before Roy settled down in Calcutta “we find a growing appreciation of the value of English as a medium of culture on the part of the educated Bengalis, specially the Hindus”. This preponderance of the view is also evident from the meeting held at the residence of Hyde East, the then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Calcutta in 1816, just about a year after Rammohun reached Calcutta. More than 50 “most respectable Hindu inhabitants of rank and wealth” including a number of Pandits met at East’s house and raised nearly half lakh rupees for setting up a college that would impart education in the European system. Those present in the meeting were the conservative Hindus opposed to Roy, who was not present in that meeting. It was this initiative that led to the formation of the famed Hindu College. Although these gentlemen were agreeable to accepting donation from East who was a Christian, they would not accept a penny from their adversary Roy.

That, of course, does not take away the substance of allegation against Roy’s advocacy for English education and induction of European science as well as morality. Almost all leading intellectuals of the time, however, can be accused of the same, including the poster boys of the Right Wing, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and Swami Vivekananda. This spirit was a reaction to the honest acknowledgement of the extremely poor quality of contemporary Sanskrit and Arabic education system, which was drastically different from the rosy picture of a thriving culture of Vedic religion and science assumed by the social media celebrity critics of Roy. For anyone interested to know, there are hundreds of easily available books and papers that demonstrate how this new system of education led to Bengal and eventually India becoming the battleground for progressive ideas over the next hundred years.

Misinformation abounds in painting Roy as a crypto-Christian too. What the critics fail to grasp is the fact that Roy was a confident person who didn’t suffer from a persecution complex. His aim was to rid conservative Hinduism of certain practices and propagate his own understanding of the religion. Unlike many others of his time, he didn’t feel that Hinduism would be in danger for his actions. On the contrary, he sought an improvement of the society through debates and arguments. In this, he was neither afraid to make enemies of the orthodox Hindu leaders of the society nor the Christian missionaries or the Islamic leaders. His criticism of the Trinitarian theology and reinterpretation of Christ by discarding the miracles and supernatural elements brought the Christian missionaries on a warpath against him.

It is conveniently ignored by these critics that it was Roy who, through his Bengali translation of the Hindu scriptures, brought more people to know about their religious traditions. One has to only read Roy’s treatise The Brahmunical Magazine or The Missionary and the Brahmun Being a Vindication of the Hindoo Religion Against the Attacks of Christian Missionaries, published in 1821 to see through the canards spread against him. The publication is a scathing condemnation of the Christian missionary efforts at converting Hindus as well as Muslims to Christianity and a rigorous defence of the various schools of Hindu theology.

The last point that I want to touch upon is that of Roy’s role in the abolition of Sati, where it is argued by the social media critics that he played into the hands of the Christian missionaries by talking against the practice. The most popular theorem now is that the practice of Sati was hugely exaggerated by the Christian missionaries in their effort to present a poor picture of India abroad. Although there is some truth in this argument, my purpose is not to debate the whole issue of the historical custom of Sati in India, but only to focus on the context by which the practice was abolished by the Government.

The fact remains that even if the numbers of instances of burning of widows can be contested on several grounds, no counter-argument challenging the government figures has been presented. It is just argued that the incidences were statistically insignificant, based on an estimate that only 2.3 out of a thousand widows in Bengal took to the practice. Firstly, this is nothing but statistical jugglery which tries to paper over the fact that between 1815 and 1828, according to official figures (different from missionary figures), 8,134 widows in the Bengal Presidency were burnt with their dead husbands.

Secondly, although his role in building public opinion cannot be disputed, Roy again wasn’t the only or even the first Hindu to appeal the government to abolish the practice. The movement against Sati had started much before he appeared on the scene, and the government had already started enacting stringent rules to regulate the practice. Arguments similar to Roy were forwarded by Mrityunjoy Vidyalankar, a Pandit of the Supreme Court, a year before Roy did so.

Thirdly, if the custom of Sati was not prevalent, what can then explain the support of the orthodox Hindu leaders towards it? After the law abolishing Sati was promulgated, two petitions signed by 1,146 members of the orthodox Hindu society were submitted to the Governor General in protest. The protest argued in favour of non-interference in Hindu customs by a foreign government but also attempted to demonstrate the scriptural sanction for the custom. If the fear of the conservative leaders was that allowing the government to tinker with Hindu customs would open the floodgate of further interference, they wouldn’t have argued about the scriptural support provided to the practice. When Bentinck refused to rescind the law and the appeal was sent to the Privy Council in England, where Roy ensured its defeat.

As RC Majumdar has observed in his lectures on Rammohun Roy published by the Asiatic Society, “The plain truth is that he was constitutionally averse to any change in the prevalent social practices of the Hindus, though he did not like and sometimes even deplored some of them”. For instance, although he condemned the caste system, he did not start a movement against it.

The efforts to vilify Rammohun Roy only shows how easy it is for uninformed persons to exploit popular sentiments to create a false narrative. It demonstrates that even in this age of easily accessible information how we feel more comfortable to hold on to our biases rather than challenge them with utilising the wealth of information. Many of Roy’s ideas were weird and impractical, but that doesn’t and shouldn’t take away even a bit from his monumental contribution to the intellectual regeneration of the Bengali and the Indian society.

Chandrachur Ghose is author of Bose: The Untold Story of an Inconvenient Nationalist, published by Penguin. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News , Breaking News , watch Top Videos and Live TV here.

Comments

0 comment