views

One is not sure what exactly is identical in the DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), the hereditary material in humans and other living organisms when RSS Chief Dr Mohan Bhagwat claimed that the DNA of Hindus and Muslims are the same, and what exactly is different when DNA test is being conducted to establish paternity or identify a crime suspect. Muslims worldwide are aware that their ancestors had been non-Muslim once, even as the Prophet of Arabia was himself born and raised into a pagan family of Mecca. However, they feel that it is Islam that brought them out of nescience. The Quran uses the term Jahiliyya — meaning ignorance or barbarism — to pejoratively describe pre-Islamic Arabia that had no dispensation, no inspired prophet, and no revealed book. Egyptian ideologue Sayyid Qutb (1906-66), asserted that the world consisted of only two cultures — Islam and Jahiliyya. (Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World, Vol.1, P.370-371).

Islam has largely been a one-way street. Most countries that went under Islam never came out of it. Even when countries like India, Spain and Greece came out of Islam, the population that had gone under Islam actually did not. In India, it resulted in partition, in Spain, expulsion and in Greece, the exchange of population under the aegis of the erstwhile League of Nations. One could come to Islam, but not come out of it. Abandoning Islam (irtidad) and deviation from religious belief (ilhad), are punishable by death in several Muslim countries. Even where there is no legal provision, leaving Islam could be no less risky while living in a predominantly Muslim society.

II

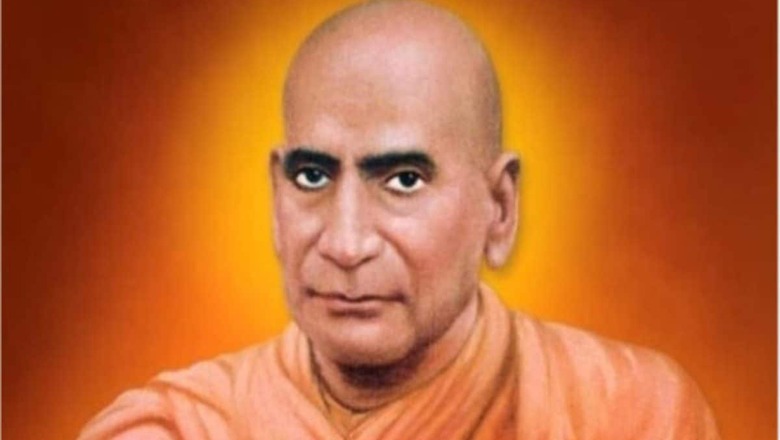

Exactly a century ago, in 1923, Swami Shraddhanand (1856-1926) of Arya Samaj piloted a historic response to Islam’s legacy of proselytizing. Called Shuddhi (lit. purification), it aimed at reclaiming the Hindus whose forefathers had gone over Islam. It is hard to deny the extraordinariness of this movement, viewed from a global perspective. It tried to disprove that Islam could have no exit door. However, viewed in the Indian context, it has some unique aspects. For example, it created a distinct literature, in languages like Hindi and Gujarati, which tried to prove that Shuddhi is scripturally and historically valid in Hinduism. Hindu society, since the medieval ages, had tried to protect itself by shunning all contact with Islam as far as practicable. It exhibited more keenness to expel its own members, who had been forced or tricked into Islam. A person who took water given by a Muslim risked being excommunicated. The Hindu society scarcely realized that it was preparing a grave for itself, by alienating its own members.

The Shuddhi literature tried to counteract the erroneous belief that reclamation is invalid in Hinduism. It might be remembered since the late 19th century, a lot of information on ancient India had come to light from archaeological, literary and numismatic sources. These lifted the veil of amnesia that had fallen upon Hindu society in the medieval ages. A medieval-era Hindu reconstructed his history through epics and Puranas but has no historical memory of ancient encounters with the Greeks, Sakas, Hunas and the expansion of Hinduism beyond the seas into Suvarna-bhumi (South East Asia). There was no printing press in India until the 18th century, which meant the dissemination of knowledge was critically restricted. Coming in the 1920s, the Shuddhi movement could take advantage of historical examples as much as the printing press. It tried to cast itself as a modern movement, creating a credible discourse to justify its actions.

Though Shraddhanand led the Shuddhi movement for a little over three years, until his assassination in December 1926, it had a long prelude lasting around 11 years. The monk narrated the incident in his book ‘Hindu Sangathan: Saviour of the Dying Race’ (1926) which stroked his interest in the subject. One day in February 1912, Shraddhanand, while visiting Calcutta, stood leisurely in the spacious hall of the Arya Samaj building. A Bengali gentleman, who introduced himself as Colonel U.N. Mukerji, on Indian Military Service, walked up to him. His Europeanized attire first prejudiced Shraddhanand against him. But Swami’s outlook changed as his visitor made a dangerous prediction, based on his computations of Census figures, that over the ensuing 420 years, the ‘Indo-Aryan Race’ (i.e Hindus) would be “wiped off the face of the earth unless steps were taken to save it”. (Hindu Sangathan, P.14)

Colonel U.N. Mukerji’s calculations were based on figures indicated in four Censuses of India from 1881 and 1911. He relied on the observations of Census of India Vol-1 (P.122) that the population of Hindus among the total population of India had declined from 74 to 69 percent. Whereas the decline was partly due to inclusion in successive Census of new areas, where Hindus, if found at all, were in the minority. Shraddhanand agreed with Mukerji that it was immaterial since they had to reckon with the population of the entire subcontinent anyway.

It might be noted that several nationalists of that period including Aurobindo Ghosh and Sakharam Ganesh Deuskar dismissed Col Mukerji’s pamphlet as scare-mongering. They argued that Muslim population growth was also moderating. What Col Mukjerji was referring to was the difference in the growth rate of the two communities, which evidently has continued even in the 21st century in independent India.

III

Swami Shraddhanand began a study of statistics that appeared to have lasted for 13 years, if not the rest of his lifetime. However, it was towards the beginning of 1923 that he put his heart and soul into the issue of Shuddhi or reconversion into Hinduism. He describes the trail of events in ‘Hindu Sangathan: Saviour of the Dying Race’. While the Indian National Congress held its annual session in Gaya in December 1922, the All-India Kshatriya Mahasabha quietly met at Agra to pass a resolution approving the reclamation of four and a half lakh Muslim Rajputs back to the Hindu fold. Commonly known as Malkana Rajputs, their ancestors were traduced to Islam in previous centuries. They were, however, scrupulously preserving many Hindu customs. This included a strict vegetarian diet, which even the Hindu Rajputs did not follow.

This meeting, dated December 31, 1922, and chaired by Sir Nahar Singh, would have remained a dead letter if the Mahasabha would not be shocked out of its complacency by the Muslim reaction that followed. A small news item in a newsweekly in early January 1923, informed its readers the appeal of four and a half lakh Muslim Rajputs for reconversion into Hinduism had been approved by the Kshatriya Mahasabha. While the Hindu response was ambivalent, the Muslim activists were roused to action to prevent this reconversion bid. Patti, a village near Lahore district, was the first to hold a protest meeting, where clerics from Deoband made fiery speeches to dash the Hindu-Muslim unity to pieces if the Kshatriya Mahasabha went ahead with the reconversion plan. The palmy days of Hindu-Muslim unity, occasioned by Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements, were continuing despite the jolt of the Mopla Riots (1921-22) in Malabar. The fierce opposition of the Muslims to Malkana Rajput’s reconversion plan alarmed the Hindus. Towards the end of January 1923, dozens of Muslim preachers, belonging to different proselytizing bodies, were active in the Malkana villages of Agra, Mathura and Bharatpur. The number of Maulvis at work in the region has swollen to 50, who had organized themselves under a strong body of Ulemas.

This reorganization of Muslim clerics shook the Hindus out of their complacency. Some Rajput and other Hindu volunteers, hardly half a dozen, went to see the actual state of affairs. A conference of different Hindu and Rajput Sabhas was called on February 13, 1923, to which Swami Shraddhanand was also invited. About 80 representatives of all dominions of Hindus (Sanatanists, Arya Samajists, Sikhs and Jains) responded to the call. In the conference, it was found that not Malkana Rajputs alone, but the Mulla Jats and Gurjars, and so-called Neo-Muslim Brahmins, Baniyas were also fit to be reclaimed (Hindu Sangathan, P.123).

The Hindu side needed an organisation, since across the divide, the Muslims were highly organized. Thus the formation of Bharatiya Hindu Shuddhi Sabha, a name proposed by Swami Shraddhanand, was announced. A managing committee was constituted and despite his reluctance, Swami Shraddhanand was elected the Chairman. The managing committee had originally planned to raise funds through private appeals for donations. However, it was compelled to appeal to the general public through the press, after Jamiyat-e-Hidayat-ul-Islam had publicly appealed for Rs 1 lakh that was endorsed by Maulana Kifayat Ullah, President of Jamiyat-Ul-Ulema, and hundreds of Muslim clerics were flocking to Agra and its surroundings to convert the Malkanas into pucca Musalman. A detailed appeal drafted by Swami Shraddhanand began to appear in various newspapers on February 23, 1923. The first batch of Malkana Rajputs was reconverted to Hinduism on February 25, 1923.

The first reconversion took place in the village Raibha, 20 km away from Agra on GT Road. The Malkanas were readmitted into the Hindu fold, in the presence of thousands of guests from outside. They all partook in food prepared and distributed by those newcomers. Swami Shraddhanand, with his towering presence on the occasion, emphasized that it was actually the Hindus who were undergoing Prayaschit (purification) for keeping outside their fold such heroic and pure souls for centuries past. The same evening another village viz. Kuthali was reclaimed. Till the end of December 1923, thousands of so-called neo-Muslims had been retrieved to the Hindu fold. While village after village followed returning to the Hindu fold, the movement spread out of the Agra region. Within three years, Swami Shraddhanand estimates, two lakh neo-Muslims had returned to the Hindu fold (Hindu Sangathan, P.130).

Another Arya Samajist who played a key role in actualizing the Shuddhi ceremony was Mahatma Hansraj (1864-1938), the famous educationist. He acted as the Vice President of the Bharatiya Hindu Shuddhi Sabha. He was not only the ace fundraiser for the project but also took meticulous care of event planning. Hansraj was careful that his profile as Arya Samajist should never meddle with the event. His biographer, Sri Ram Sharma (of DAV College, Lahore), states the Malkanas were not being admitted into the Arya Samajic fold, but coming back to occupy their original position in Hindu society as organized into caste and sub-caste groups. Thus, they were not becoming Hindus alone, but Rajputs of a particular sub-caste (Mahatma Hansraj: Maker of the Modern Punjab, P.210). The actual ceremony of Shuddhi was performed by orthodox Pandits, according to orthodox rites, and not Arya Samaj rites. Hansraj held several rounds of consultations with leaders of the Hindu orthodox section. It was decided that the ceremonies would be “neither so elaborate as to wound the susceptibilities of the Malkanas nor so perfunctory as to make it possible to suggest that they were not efficacious (Mahatma Hansraj, P.211). During the three months Hansraj spent in the region, according to his biographer, the Shuddhi work had spread to 147 villages, and more than 30,000 Malkanas had been brought back to the Hindu fold (Mahatma Hansraj, P.219).

IV

Shuddhi was no stealth exercise, barren of intellectual discourse. A series of books were written in Hindi and other languages to establish its scriptural sanctity and historical validity. One such book ‘Shuddhi Chandrodaya’ was written by Chandkaran Sharda, Sharda, who had earlier taken part in the Non-Cooperation Movement, and was disillusioned about the Hindu-Muslim unity of Gandhian kind in jail when he found Khilafatists were trying to convert fellow Hindu inmates into Islam. He traces the validity of Shuddhi down from the Vedic to Mughal times. Another work ‘Shuddhi Shastra’, edited by Pandit Rajaram, attempts to justify Shuddhi on the historical lines. Such works actually were meant to convince the possible critics of reconversion amongst orthodox Hindus.

The popularity of the Shuddhi movement is believed to be a factor in the assassination of Swami Shraddhanand in December 1926, by a Muslim fanatic Abdul Rashid.

Mahatma Gandhi was never happy with the Shuddhi movement. “In my opinion”, writes Gandhi (1924), “there is no such thing as proselytism in Hinduism as it is understood in Christianity and to a lesser extent in Islam. The Arya Samaj has, I think, copied the Christians in planning its propaganda. The modern method does not appeal to me” (MGCW Vol-28, P.56). The real shuddhi movement, felt Gandhi, should consist of each trying to arrive at the perfection of one’s faith. It is evident that Gandhi did not contemplate the historical and sociological impact of Islamic conversion on Hindu society. A “perfection” of the Islamic faith, for an Indian Muslim, might mean giving up every vestige of Hindu element as Kufr, as is proposed by Tablighi Jamaat.

A different approach was taken by Veer Savarkar. Savarkar (1938), while hailing this feat of Swami Shraddhanand, observes that “in a country like India where religious unit tends invariably to grow into a cultural and national unit, Shuddhi movement ceases to be merely theological or dogmatic one, but assumes the wider significance of a political and national movement. If the Moslems increase in population, the centre of political power is bound to be shifted in their favour, as it has already done in some provinces of India” (A Review of the History & Work of the Hindu Mahasabha and Hindu Sangathan Movement by Indra Prakash, P.xi-xii). It might be remembered that Hindu Mahasabha had lent its support to the Shuddhi project as early as 1924 before Savarkar joined the Mahasabha.

A full century has passed since the first notable act of Shuddhi in modern India. India, partition notwithstanding, faces renewed imbalances in religious demography-affected politics. In the 2011 Census, the Hindu population fell below 80 percent for the first time in independent India. The new Census may throw up a more damning picture. While a Hindu nationalist party might be ensconced in Raisina Hill today, an anti-climax could catch up with shifting religious demography. The ‘lathi arm’ of Hindutva, the RSS, has conveniently buried its ‘Ghar Wapasi’ programme and wishes to convince the nation about the sameness of DNA in Hindus and Muslims. It has recognized Gandhi as the “Hindu Patriot”, though he opposed the Shuddhi, and described the assassin of Swami Shraddhanand as his brother. Fortuitously, DNA was not a popular term before Watson and Creek discovered its double helical structure in 1953, and Swami Shraddhanand and Mahatma Hansraj did not fall for it.

The writer is author of the book “The Microphone Men: How Orators Created a Modern India” (2019) and an independent researcher based in New Delhi. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment