views

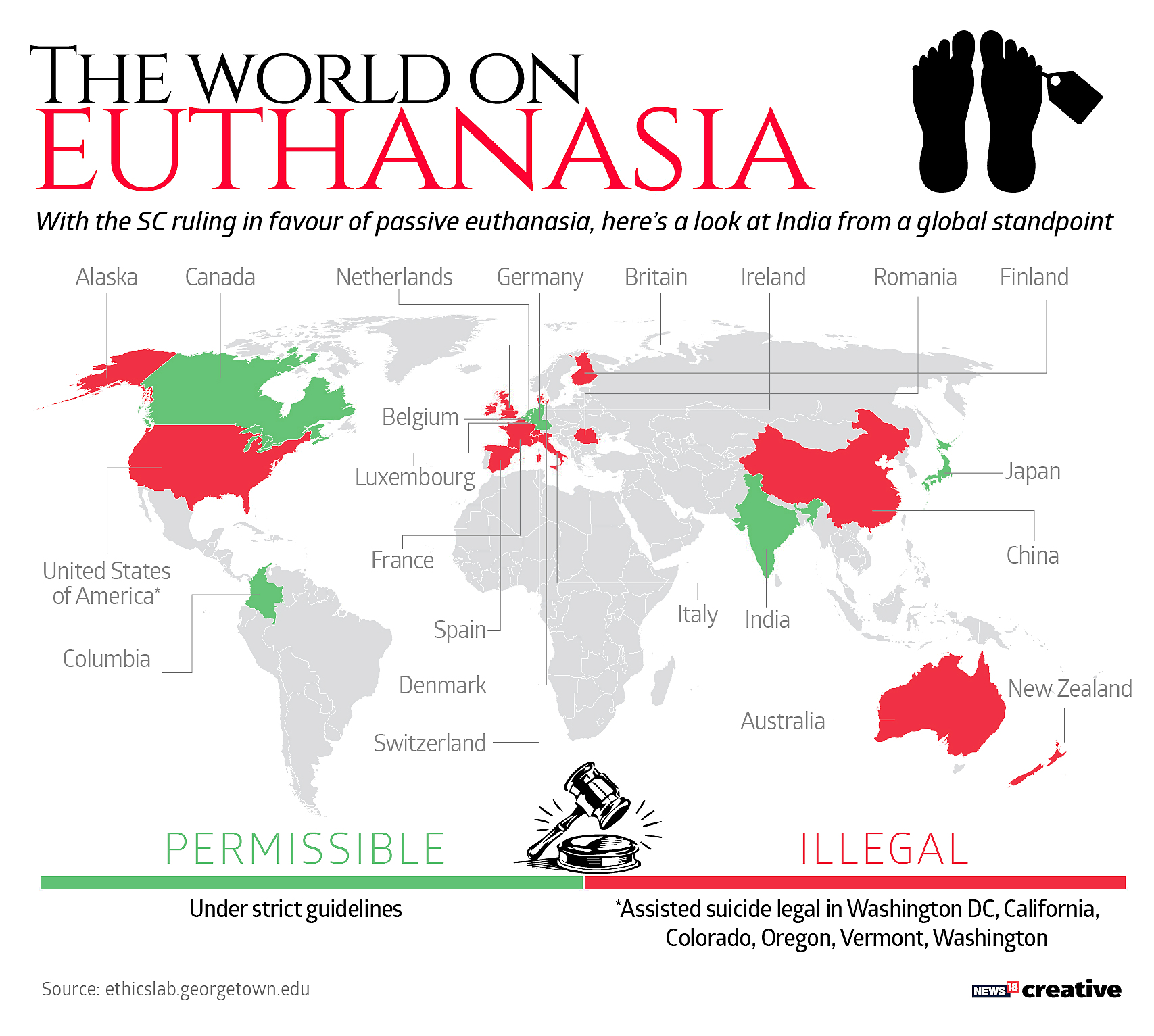

New Delhi: A five judge bench of the Supreme Court, headed by Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra, on Friday legalised the right to die and approved ‘living will’ made by terminally-ill patients for passive euthanasia.

As the court began hearing the case a year ago, this case was a step ahead from the Aruna Shanbaug verdict where although the court rejected the mercy killing plea, but allowed passive euthanasia in India.

Then why is today’s verdict so significant? What are the possible repercussions of recognising a living will? News18 explores:

What is Passive Euthanasia?

Passive euthanasia is a condition where there is withdrawal of medical treatment with the deliberate intention to hasten the death of a terminally-ill patient.

What is a Living Will?

Living will is a written document that allows a patient to give explicit instructions in advance about the medical treatment to be administered when he or she is terminally-ill or no longer able to express informed consent.

It is a concept associated with passive euthanasia. It is a legal document which allows you to express your wishes to doctors in case you become incapacitated. In a living will, you can outline whether or not you want your life to be artificially prolonged in the event of a devastating illness or injury.

Why a verdict on passive euthanasia again after Aruna Shanbaug?

This verdict which is set to be delivered is not primarily on passive euthanasia or its legality.

Last year, on October 11, the Centre had categorically informed the Supreme Court that “passive euthanasia” was the law of the land and that the government was in conformity with it.

The top court in its verdict on March 7, 2014 in Aruna Shanbaug case had permitted passive euthanasia or passive mercy killing under certain circumstances, provided it was backed by the permission of the high court concerned.

What is the origin of this case then?

The constitution bench is set to deliver its verdict on a plea by NGO Common Cause seeking that a person should be allowed to make a living will stating that all medical support should be withdrawn if, in the opinion of the doctors, he is in that state of terminal illness where a turnaround is not possible.

The petition seeks the enactment of a law on the lines of the Patient Autonomy and Self-determination Act of the USA, which sanctions the practice of executing a “living will” in the nature of an advance directive for refusal of life-prolonging medical procedures in the event the person is no more in a condition to give consent.

Did the court rule on this particular matter before as well?

The matter was first disposed of by the apex court in February, 2014. However, while dealing with this matter, the court had refrained from pronouncing any order but referred the matter to a constitution bench to ensure that areas of conflict between the Aruna Shanbaug case and Gian Kaur case could be ironed out.

While the Shanbaug verdict allowed passive euthanasia under certain safeguards, the 1996 verdict in the Gian Kaur case held that ‘Right to life does not include Right to Die’.

What is the contention by the petitioners?

The primary basis of the petition is, “How can a person be told that he/she does not have right to prevent torture on his body? Right to life includes right to die with dignity. A person cannot be forced to live on support of ventilator. Keeping a patient alive by artificial means against his/her wishes is an assault on his/her body.”

Senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan who was the amicus curiae in the case had stated that after Aruna Shanbaug case it was only the legal guardian or a medical board who could decide whether life support could be withdrawn to a terminally ill patient, but the person suffering from such terminal illness cannot decide.

Bhushan pleaded for active euthanasia to be allowed by saying that a person facing the only option of leading a life with suffering and pain, should have the sole right decide whether he should put an end to life with dignity.

Is the government opposing it?

Yes, although the government has no problem with practicing passive euthanasia as devised under the Aruna Shanbaug verdict but it has opposed living will in principle.

The government had opposed the concept of Living Will and the Medical Power of Attorney in case of terminally ill patients. The government has argued that consent expressed in the Living Wills could not be considered as “informed”, because the persons who opt for it may not be aware of future medical developments, which can later lead to betterment in the condition of the terminally ill patient today. The government has also expressed reservations stating that what if the person who has made a ling will decides to withdraw such a will when he is no more in a condition to give consent.

Has the government considered a law on this subject?

During the last stage of the hearing close to October, 2017, the government had told the constitution bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra, Justice A K Sikri, Justice A M Khanwilkar, Justice D Y Chandrachud and Justice Ashok Bhushan that a draft bill permitting passive euthanasia with necessary safeguards was already before it for consideration.

The Management of the Patient with Terminal Illness Withdrawal of Medical Life Support Bill was stated to be before the government.

The draft bill was originally authored by the Law Commission and was annexed with its second report on passive euthanasia. However, the government had later appointed a committee of senior doctors which after considering suggestions from public framed the final draft that is now before the government.

What does the draft law contain?

The latest amended bill is not still available on the public domain, but the draft law as accessed by News18 still has Central government expressing its reservation to permitting "living will" both on grounds of "principle" and "practical" considerations.

The bill has called the will of a person to be or not be given medical treatment in case he or she falls terminally ill as "living will" or "advance medical directive" in the drafted bill. The bill proposes that any such will or a medical power of attorney will not be binding on any medical practitioner and cannot be executed by any patient since it would be considered void.

The bill has clearly outlined a difference between a competent and an incompetent patient where it has been stated that if a person who is above 16 years of age and can understand consequence of his decision and makes an informed call about denying medical treatment, then such a decision would be binding on the doctor attending him and would eventually lead to passive euthanasia.

Though the bill does not mention the word 'passive euthanasia' but it states that 'life sustaining treatment' can be refused by a competent patient and such a decision will be binding on the doctor.

What is the role of a medical board here and what might the court rule?

As the court upholds to the right to die in its verdict today, CJI Dipak Misra during reserving the verdict had noted that it will lay down guidelines for drafting living wills and how it can be authenticated.

The five judge bench while reserving its verdict had said that if the right to dignity in death was to be recognised, then there has to be some room for dignity in the process of dying too.

CJI Dipak Misra had observed that a person’s advance directive intended to die with dignity should take effect only when a medical board affirms that the person’s medical condition was incurable and irreversible.

It was proposed by Justice AK Sikri that a certificate from a statutory medical board citing that a patient’s condition is beyond cure and irreversible would take care of the fear of relatives and doctors about withdrawing life support. Later Justice Chandrachud also suggested a twofold test to check how the living will would take effect.

Firstly, will can take effect when the medical condition of the patient is irreversible and the second one would be when prolonging his life by machine support would only lead to his pain and suffering thus in a way living will was a will for right to live and not die according to Justice Chandrachud.

However, the government has made it clear that it is afraid about people who are not privileged and would be susceptible to “abuse if euthanasia and living wills are legalized” in the country.

Comments

0 comment