views

Will a day come when India's poor can access government services as easily as drawing cash from an ATM?

The day will come very soon when transfers from the government will be as easy, or easier, than using an ATM. But transfers to the poor are a very small part of what any government does. And no country in the world has made accessing education or health or policing or dispute resolution as easy as an ATM, because the nature of these activities requires individuals to use their discretion in a positive way. Technology can certainly facilitate this in a variety of ways if it is seen as one part of an overall approach, but the evidence so far in education, for instance, is that just adding computers alone doesn't make education any better. And no one should imagine that solving hard policy problems are made any easier by technology.

The dangerous illusion of technology is that it can create stronger, top down accountability of service providers in implementation-intensive services within existing public sector organisations. One notion is that electronic management information systems (EMIS) keep better track of inputs and those aspects of personnel that are 'EMIS visible' can lead to better services. A recent study examined attempts to increase attendance of Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANMs) at clinics in Rajasthan, which involved high-tech time clocks to monitor attendance. The study's title says it all: Band-Aids on a Corpse. Adding 'e' to everything sounds cool but e-governance can be just as bad as any other governance when the real issue is people and their motivation.

For services to improve, the people providing the services have to want to do a better job with the skills they have. A study of medical care in Delhi found that even though providers, in the public sector had much better skills than private sector providers their provision of care in actual practice was much worse.

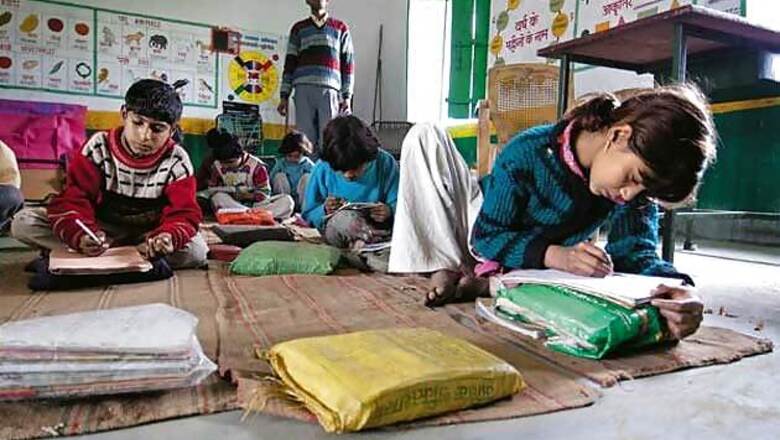

In implementation-intensive services the key to success is face-to-face interactions between a teacher, a nurse, a policeman, an extension agent and a citizen. This relationship is about power.

Amartya Sen's Pratichi Trust report on education in West Bengal had a supremely telling anecdote in which the villagers forced the teacher to attend school, but then, when the parents went off to work, the teacher did not teach, but forced the children to massage his feet.

A nationwide survey found that 29 per cent of children in government schools were pinched or beaten in the previous month—and that this was twice as prevalent for the poorest versus the richest students.

As long as the system empowers providers over citizens, technology is irrelevant.

The answer to successfully providing basic services is to create systems that provide both autonomy and accountability. In basic education for instance, the answer to poor teaching is not controlling teachers more through top-down controls. This leads to the current perfect storm outcomes in which everyone—including the teacher—is unhappy with a dysfunctional bureaucracy that attempts to control everything and really controls almost nothing. The key to good basic education is to hire teachers who want to teach and let them teach, expressing their professionalism and vocation as a teacher through autonomy in the classroom. This autonomy has to be matched with accountability for results—not just narrowly measured through test scores, but broadly for the quality of the education they provide.

A recent study in Uttar Pradesh showed that if, somehow, all civil service teachers could be replaced with contract teachers, the state could save a billion dollars a year in revenue and double student learning. Just the additional autonomy and accountability of contracts through local groups—even without complementary system changes in information and empowerment—led to that much improvement. The first step to being part of the solution is to create performance information accessible to those outside of the government. This is going beyond the right to information about what the government actually does to create a wealth of information about how well the functions are carried out.

But, paradoxically, in order to do more, the government of India has to do less. One of the key problems is that the government is promising to do more than it is capable of actually doing by creating 'rights' and 'entitlements' without creating any additional capability of the state. If every village is promised water or roads or a clinic and there is really only enough budget for half the villages to get it, then this introduces discretion into the decision of who gets water. It introduces more corruption and a lack of transparency. The only way to have transparency and accountability—and hence reclaimable rights on the state—is to promise what the state has the capability to deliver.

(As told to Sujata Srinivasan)

Comments

0 comment