views

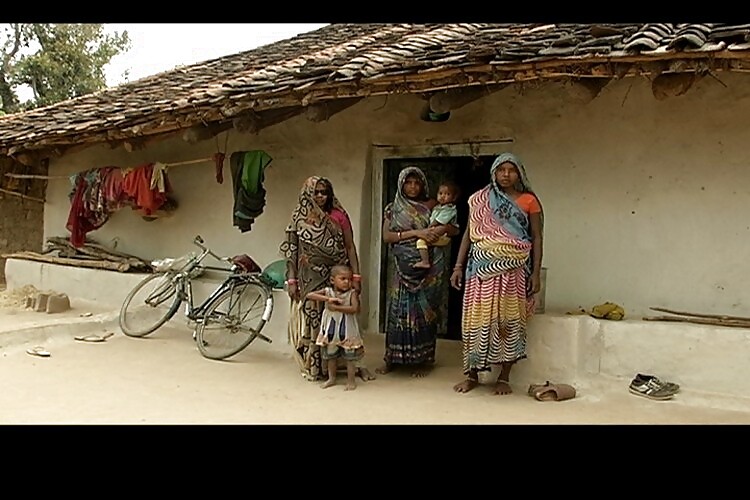

It's lunch time in Bundelkhand's Gudrampur village. Shyama knows the four hungry children waiting patiently will soon be restless. She is glad her sister-in-law Chunni Bai is helping.

She is expecting her third child and pregnancy makes her tire easily. In the ninth month now, it's impossible to trek the 10 km circuit to collect firewood from Kadhaili and then sell it at the Fateganj market. She would make Rs 25 for a single bundle and it would have been extremely useful. Her husband Rajendra has moved to Kota to look for work as there is very little work in the village.

"We prepare chapati (roti) and eat it with salt. In the evening we have salt and rice. This has been the situation for the last 3-4 years," says Shyama. Chunni Bai adds, "We will have salt and chapati in the night. It will be the same tomorrow."

ALSO READ: As Bundelkhand battles famine, schemes and packages fail to deliver

The moment chapatis are ready, the young children walk up to the fireside, some as young as four and six years, pick them up, then go to the place where the salt is kept, gather some salt, sprinkle it on their rotis, dust off the excess salt, roll them up and start eating them.

A girl child Parvati, barely four years old, picks up a chapati, sprinkles some salt and gives it to her brother. It is what they are calling a square meal in the forgotten, dry and parched landscape called Bundelkhand which is spread across Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

"There is very little to eat. Gram crop has failed. There is no work. I worked for 10-15 days on a road project but have not yet been paid for the same," says Shyama.

But Shyama is one of the lucky few as she has some wheat stock. Others in Gudrampur which is in the Naraini block in Uttar Pradesh's Banda have even less.

ALSO READ: Lakhs migrate from Bundelkhand without any dream or money

After all this is the third season of distress. Excessive rain in 2014 has been followed by drought in 2015 which stretched an already fragile safety net to breaking point.

The taste of pulses (dal) is a memory. As there is no arhar growing in the fields, so it is off their plates. At Rs 100 a kilo, arhar is simply out of reach.

Gudrampur is a picturesque village but it hides deep poverty within. Most of the households in the village do not have any food reserves.

Across Bundelkhand similar sights are visible especially in villages that are close to forests. Two meals are hard to come by and if they do, they are meagre with salt replacing all other elements of a meal.

"Today I have prepared roti. We will eat it with salt. Yesterday we had roti and potato. In the night we had 'kaithi ki chutney'. We also have salt. Where is nothing else then we have salt," says Laxmania, a tribal (adivasi) woman.

Sadhu Ram says he had roti with jaggery. "I am unwell, so I have roti and jaggery. I have only jaggery. There is nothing else to eat."

"Today we are having milk and roti. Yesterday we had roti and salt in the morning as well as evening. Tomorrow again we will have roti and salt," says another resident Siya Bai.

When asked how she can afford milk, Siya Bai replies, "I have Rs 10 from which I bought some milk. Earlier the drought was not round the year and we were not forced to eat only roti."

"It is only salt and roti. Yesterday also it was salt and roti. We cannot have potato every day. Tomorrow also we will have salt and roti," adds Siya Kali.

They all belong to the adivasi community who don't own land but practice batai, which means they cultivate the land on rent. They invest in the seeds, labour and fertilizer and share the harvest, if there is one, with the landowner.

Shyama and Chunni have borrowed Rs 5000 from a local money lender to cultivate wheat, arhar and jowar in the Rabi season. But if it doesn't rain or rains poorly then they harvest nothing. But they will still owe interest on their loan.

"There is loan. We have to repay it to the money lender," says Shyama.

Even an indirect government support to fight hunger is missing. The primary school where students could have got at least one meal via the Midday Meal Scheme was shut well before the closing time of 4 pm. Villagers say the appointed teacher never comes and the one paid to keep the school running doesn't teach.

"We stopped the midday meal as there are very few students. Should I go to their (students) homes if they don't come to school. There are many children in the village but I don't have a count. The teacher comes once a week. His name is Rakesh but I don't know his full name," says the caretaker.

Bhim Kumar Yadav has seen the crops of chana (gram), masoor, arhar, laahi fail one by one. He scrapes the top soil off to show the chana seeds sown in October 2015. No rain and the complete absence of moisture in the soil has shriveled up the seeds. The few that did sprout died soon after.

"It is of no use of 90% of the people are in distress and only 10% are well off. It doesn't matter if they eat or don't eat. We get wheat and rice from government quota. We buy and somehow survive. If irrigation facilities are provided to us, then the government will profit. The soil here is very rich and can yield gold. Everyone survives because of this soil. Life stops if there is no water. This is not a drought but a famine," says Yadav.

At Shadasaani, a village in the Kamashin block that is close to the town, Subhadra Devi is sitting through a third consecutive day of no work. There's nothing for her or her husband either in the fields or under the Mahatma Gandhi Nation Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA).

Her PDS card is over limit. She has got some wheat flour from the flour mill on credit and her family will have plain dalia or roti with salt. Potato which is selling at Rs 7 to Rs 10 per kilo is the only other thing she can afford but even that is not in the house.

"I went to the shop to buy potato. I wanted it on credit. But I was given a rotten potato. I cooked the same potato. We need to fill our stomach and so I bought it. At least the children can have some food. There can be disease due to rotten food. But what can we do? We are helpless. We had never seen such a situation. There is nothing else. There is no milk," she laments.

Her son Amit, sprinkles some salt on his roti, dusts it off with another one and starts eating. The bowl next to his plate has just some more salt. Her daughter Kiran has just wheat porridge. There is nothing on her plate either. Both Amit and Kiran had their food without any complaints or demands.

Subhadra Devi has her food after feeding her children and her husband. "When my son asks me for milk, I tell him, you have to grow up and earn to have milk. Milk costs Rs 30 a litre. We do not have a goat or a cow. How can we afford that," she asks.

But there is a bit of good news in this bleak landscape.

Shyama has delivered a healthy baby. Both she and the girl are fine. Her husband has sent Rs 5000 home to help tide her over with the new born. The child doesn't know yet but 'akal' or famine is a word she will hear a lot.

Comments

0 comment