views

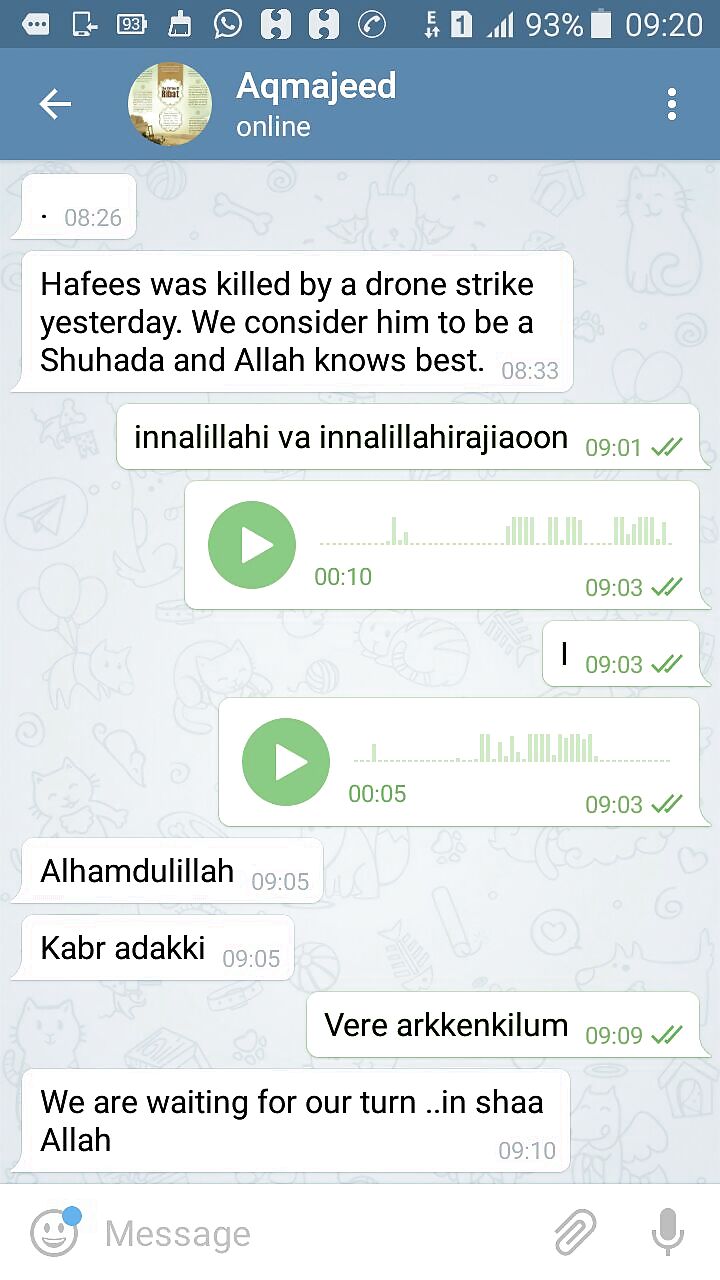

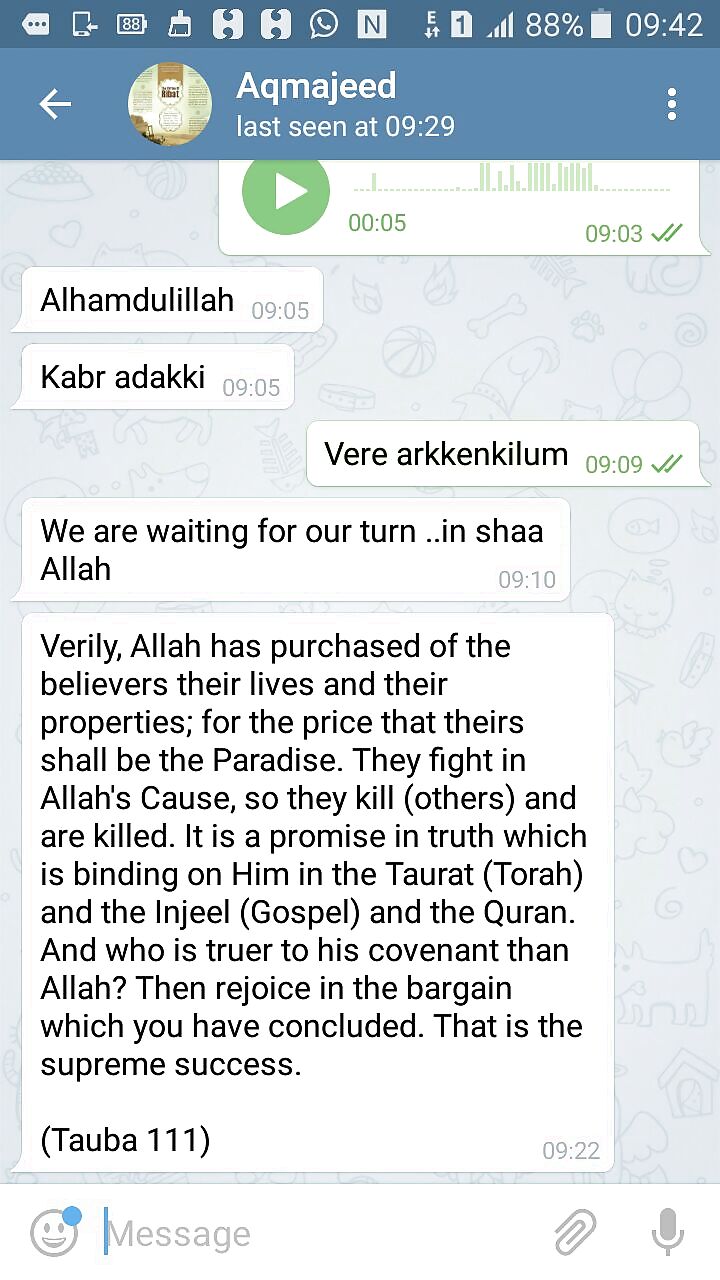

Kannur/ Kozhikode: Four minutes after they received a message on an app that their son who had joined the dreaded Islamic State was no more, Hafesudheen Koleth’s family had one question to ask: “Anyone else?”

The response: “We are all waiting for our turn, Inshallah.”

The reply came from Ashfaq, Hafes’ friend, who had messaged his family to inform them that their son is no more. In fact, that he is buried.

One thing that binds the families of Hafes and 20 other youngsters who had run away to join jihadist causes in Syria and Afghanistan in mid-2016 is the fear (and perhaps the inevitable acceptance) that death is not far away.

Hafes was 24, when he told his family that he was going away to study the Quran in Kozhikode. A few days later, the family got a message saying he won’t be returning.

These 21 people –three of them women -- who decided to travel out last year have left families behind who have been living in a dilemma ever since – mothers who ache for their sons, but who are forced to distance themselves from their own to still live on with some semblance of normalcy in their neighbourhoods.

Take the case of Subhani Haja Moideen, among the six persons arrested by the NIA in October 2016, for allegedly conspiring to take up jihadi activities.

His brother and aged father, who have lived in their ancestral home in Thodupuzha in Idukki, snapped ties with their son more than three years back and are determined to keep it that way. Ashamed to go out even within his own community, his father keeps to himself most of the time.

In nearby Kanakamala, from where Subhani and his friend Manseed were arrested along with four others, Manseed’s sister (name withheld) is yet to come to terms with what their lives have become.

She remembers vividly that day in early October, when the NIA arrested her brother. “When the officers came here for an enquiry and started seizing documents and phones, my mother fell unconscious. Her blood pressured dropped and she didn’t come to her senses for more than a day,” she told News18.

First the disbelief. Then the attempts to call her brother, try to get him on the line to reassure them there was perhaps a mistaken identity. Then the slow realisation that this is not a bad dream. Wondering if their ‘boy’ was being framed, should they take this up legally. All comes together in a rush.

Neighbours knocking on their doors for updates – suspicious, digging for information – wondering whether Manseed’s growing a long beard had anything to do with radicalisation. Questions, doubts, shock. A sick mother to take care of.

Among those radicalised are bright students who dropped out of professional courses as they felt it was ‘un-Islamic.’ They are youngsters looked upon with great hope by their families – as Gen-Next who will significantly improve the families’ fortunes once they finished their degrees.

Among the 21 who ran away to Afghanistan in pursuit of jihad, four were converts: three were originally Christians, one a Hindu (two Christian brothers and their wives) from Palakkad.

One of the wives is Nimisha, a promising dental college student who threw away her education just before her final exams, to move to Afghanistan. She was also seven months pregnant at the time.

Over the last few months Nimisha’s mother Bindu has sought out government officials and NIA officers to track down her daughter. Bindu believes her daughter was brainwashed, but the government could still get her back.

The last she heard from Nimisha was a message from her last July, saying they were traveling via Sri Lanka, and later a call from her son-in-law in October, informing her of her grand-daughter’s birth. She was told the women are separated from the men, so he couldn’t give the phone to his wife to talk to.

Today, confronted with the news of Hafesudheen’s death, she only says, “I don’t want to listen to all this negativity. I am sure my daughter will come back one day, with my grand-daughter. I leave it to the Almighty.”

It’s not just the families of those who have run away, who are worried. There are others who notice sudden changes in their children, who wonder what went wrong.

Picture this: A brilliant engineering student suddenly informed his family last July he wants to discontinue his BE course. Reason: There are girls in his class and he believes that, according to Islam, he should not look at the face of any girl other than his mother or sister. No amount of reasoning by his father or elders helped: he stopped attending college.

“The changes in my son were sudden. He used to dress like normal children his age, but suddenly he started wearing very cheap clothes, changed from jeans to mundu and kurta-type clothes. He became reserved, stopped watching movies, songs and even news. The only thing he does is reading the Quran and praying,” says the father, a government official in his fifties. He has been growing increasingly worried about his son shutting himself off from ‘normal’ ways.

Teary-eyed, he said he had tried to take his son to many scholars from the community for counselling, but it had no effect. With just a few years to go before retirement, he and his wife are shocked and scared about the future.

“He would go back to interacting with scholars in the Gulf online. There are also some groups in Kozhikode that promotes this type of extreme spiritualism. I don’t know what will be the future of my son. At night, my wife and I just sit and cry… There are even moments when we have thought of ending our lives,” he told News18 in an interview towards the end of last year.

He is deeply aware that there are more children who are being brain-washed into radical thinking. There are those who refuse to use public buses, because the government uses tax money collected from ‘haraam’ activities like lottery and sale of liquor. There are those who refuse to travel in cars bought on loans.

Most are radicalised by what they see on the Internet – it may be a minuscule percentage, but if not nipped in the bud by both government agencies and community leaders, this could worsen.

“Parents don’t speak out due to fear that the children may be branded as terrorists or ones with ISIS links. Many are ashamed to speak out about their trauma and are dying within,” he says.

Muslim organisations have, in recent times, stepped up campaigns to fight efforts at radicalisation. General Secretary of the All India Islahi Movement, Dr Hussain Madavoor, says speeches, seminars, publications, public awareness meetings all focus on distancing youth from the ISIS way of thinking.

“All major Muslim organizations have declared that IS is anti-Islamic, IS is extremism. It is not a threat, I believe. There are 90 lakh Muslims in Kerala. Of all this 25-26 people disappearing – that is not even 0.001 percent. That is not a threat, but we want to teach our youngsters and all our people that this is not Islam, this is not religion,” Dr Madavoor says.

Comments

0 comment