views

Chandarpara (Pakur District): When Monowara lost her eldest son in 2005, it was not sadness that engulfed her home, but a sense of worry. Monowara had to start working to feed her eight other children. With no ration or widow pension, all that she could do was to wait for her then eight-year-old son to be old enough to work as a temporary labourer.

Thirteen years later, Monowara still lives in a small hut in Jharkhand’s Chandrapara village in Pakur district. She makes and sells bidis with the help of her children.

After struggling to make ends meet, Monowara realised neither could she work as a domestic help anywhere near the village nor could she be a temporary labourer as her spinal pain increased every time she bent down.

On most days, she manages to make 250 beedis. But on days her children don’t manage to sell enough, there’s no food at home. She either asks her neighbours for food, or they sleep hungry.

(The villagers thrive on the income earned by the women by selling beedis. Photo: Debayan Roy)

The village of Chandarpara lies a few kilometers to the west of the Ishaqpur panchayat of Pakur district in Jharkhand. The dwindling alleys in the village lead to the rustic railway line. Across the railway line, the roads are dotted with mosques, sweetmeat shops and bare-bodied children humming “kit, kit, kit." The village’s similarity with Kolkata’s small localities is uncanny.

Like every other Jharkhand village, Chandarpara is marred by ill-maintained roads and with no sign of any employment generating industry. About 3,000 villagers reside in the eastern end of Chandarpara. Though most of them are Bengali speaking Muslims, they trace their ancestry to Chandarpara itself.

Monowara keeps looking out of her one room hut while making her pack of beedis. “Dorod je ki aapni bujhben na, khawar jonno onek kichu korchi (you will not understand the pain, we have to do a lot for food)," she said.

“I don’t have ration card. I don’t even know the reason why I was denied the ration card. Whenever I visit the office, they ask me to come back later," she said.

After her husband died four years ago, she made several trips to the office of the Sub-Divisional officer and the collector to get access to her widow pension. She never received it.

Monowara and her eight children including (the age of the youngest kids) make beedis to run their home. But she doesn’t like the fact that she had to even get her youngest daughters in the bidi making business. “Even my youngest daughter makes these beedis with me. The days I don’t have money, I have to beg from my neighbors," she said.

(Monowara Bewa has been making continuous applications to the officers for either widow pension or ration cards, but still remains hopeful. Photo: Debayan Roy)

The Bengali spoken by the villagers is laced with an accent that’s strikingly different from the language spoken in Dhaka, but locals say that the language has been a native to the district.

Ustad Noor, the man who has been giving the muezzins call every morning for the last 30 years, said that the official records dismisses any doubts about the native language. “The main languages of Pakur is Bengali, Santhal, Pahariya and Hindi too," he said.

While there may be a confusion about the language, the one thing that’s clear is that when Jharkhand’s 1250 villages got access to ration card, this one was left behind.

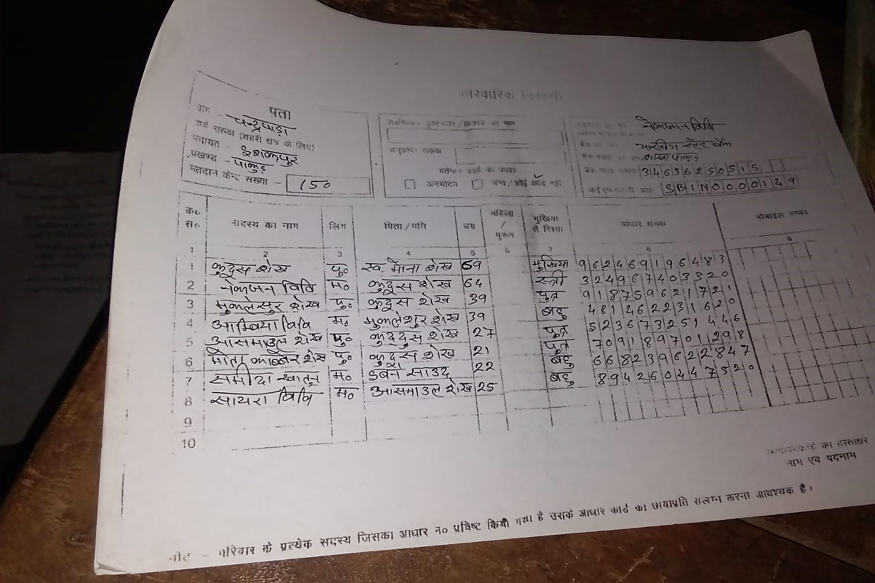

(A page from the consolidated list of villagers who need ration. Photo: Debayan Roy)

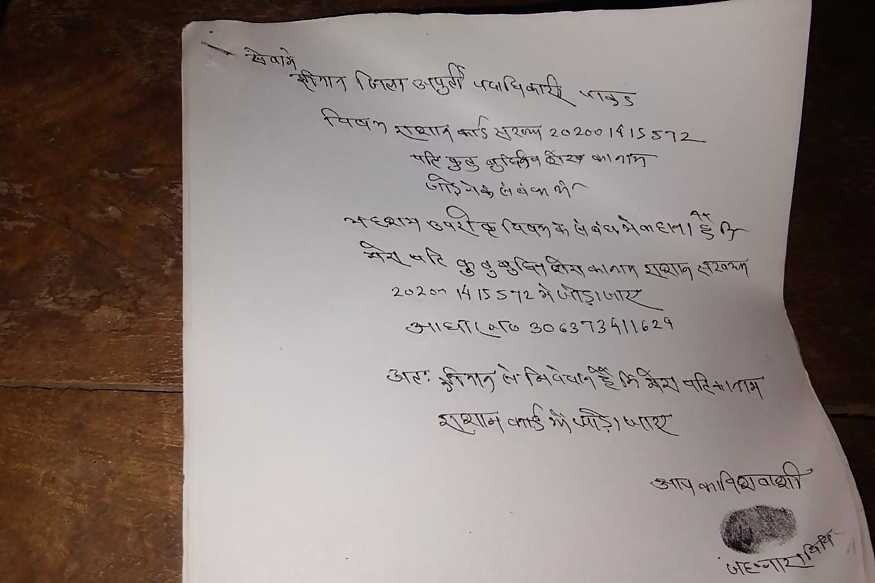

“We are the only one left out," said Noor. But why would an entire village be kept out of bounds for ration cards? Mohammad Muzaffar Hussain, who has become ‘Dada’ for the entire village, had not only written letters to the District collector and zilla officers but also made several trips to meet these officers. But nothing came out of it.

The villagers allege that they were excluded during the last population census held in 2011 and as a result none of them received ration cards.

“According to the 2011 census, Inshaqpur panchayat consists of five villages. Chandrapara is also a village. While one half of Chandarpara was included in the census data, the other half was left out. The villagers from the one that was left out has no ration card," said Hussain.

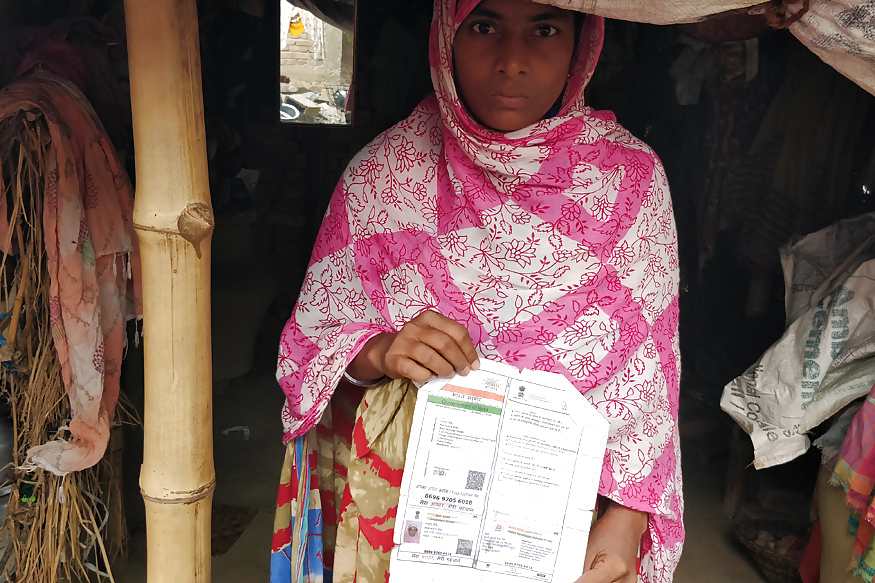

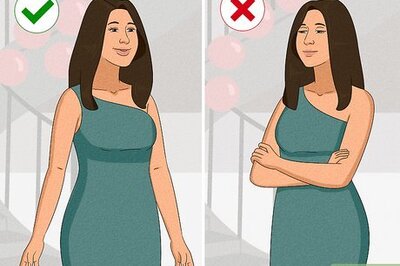

As Hussain speaks, about a hundred odd women gather in the empty field in the village. Most of them have the basic identity cards-- Aadhaar and Voter ID; but the absence of ration cards make their life particularly difficult.

(Aadhaar cards and voter IDs have all proven to be futile for villagers trying to get ration. Photo: Debayan Roy)

While all the neighbouring villages get ration, the villagers of Chandrapara struggle to travel to cities and make money to afford a morsel of rice. For many, especially the elderly, the only way to avoid hunger is to wait for funds from the local mosque to buy food or, to beg.

The local mosque in the village has made a fund where families that can afford to buy food put in money. Villagers who are unable to make ends meet can ask for Rs 5 from that fund to buy rice and pulses.

(Villagers have written letters to Zilla officers and even the Food minister to urge them to take action, but still await a response. Photo: Debayan Roy)

Quddu Shaikh, 63, often sits in his dilapidated balcony, waiting for the mosque collection to reach his home. “I have been staying here for over 40 years. We first used to make applications to our school master, but we never got ration cards. Then one side of Chandarpara got ration cards but another half was left out. We were asked to do register online, but that didn’t work either," he said.

(Many elderly in the village like Quddu Shaikh depend on the money collected by the local mosque for survival. Photo: Debayan Roy)

Shaikh said that despite submitting their identity cards including Aadhaar, they never got ration cards. “We have a record of all of this," he said. Shaikh, who stays with his wife and younger son, usually depends on the collection from the local mosque. “I don’t earn anything now and neither do I have the support of PDS," said Shaikh, explaining his dependence on the fund.

Hussain ‘Dada’ has been told that the only way the villagers can get access to ration cards is if the ones who already have the card and are financially sufficient get their names deleted from the list.

“Zilla officer had told us that first we need to intimate them about the names of individuals who have ration cards so that the people who are sufficient can be deleted from the list. But who is responsible for that, the Gramin officers or me?" Hussain asked.

Though the younger ones travel with their parents to the cities to earn a living, most of their parents are forced to stay back and fend for themselves. Mamata ‘Bewa’ refuses to even peek outside her long drawn pallu (veil) over her face. It’s been 12 days since she lost her husband. And it’s been nine days since she had a morsel of rice at home.

In Ishaqpur's Chandrapara, widows refer to themselves as ‘Bewa' (a colloquial Bengali word used for widows) and it slowly becomes an inseparable part of their identity. As Mamata talks about the hardships, she struggles to remember to add ‘Bewa’ to her name.

Mamata’s one room hut, unlike the others, does not have an open space in front of it. A blocked canal runs right in front of her door. While her veil is supposed to be a guard against “other men", it actually helps in blocking the obnoxious smell from the canal pervading every inch of her home.

Mamata had first started applying for her ration card in early 2000 but soon lost hope. “How many times should I visit the local dealer only to return humiliated?" a question that none of the villagers have an answer to.

“My husband was a daily wage earner. Now, all I can do is beg from neighbors who are equally starved as me," she said. Others, too, face the same fate as Mamata here. They are tired of writing to the ward members for inclusion in the ration card list and arrange a “shop for subsidized grains." They have been disappointed too many times now.

Shonali, mother of four, has discovered a way to ensure her babies don’t cry when they are hungry. “Bacha hole iktu tambaku mukhey dhukaiya di, ghumai porey, kono doodh chaye na, (We usually rub a bit of tobacco in a baby’s mouth when they cry for food. They don’t want milk then, they sleep after that)," she said, while preparing her evening meal of water and some puffed rice.

(News18 tried to reach out to Dileep Kumar Jha, Deputy Commissioner, Pakur and Jitendra Kumar Deo, Sub Divisonal officer of Pakur. However, both of them were unavailable for comments.)

(This story is the second part of a series by News18 on the starvation deaths in Jharkhand)

Comments

0 comment