views

Planning Your Research Statement

Ask yourself what the major themes or questions in your research are. Outline the main questions that drive your research and that you strive to answer. Write these questions and topics down so that you’ll be better able to articulate them in your research statement. For example, some of the major themes of your research might be slavery and race in the 18th century, the efficacy of cancer treatments, or the reproductive cycles of different species of crab. You may have several small questions that guide specific aspects of your research. Write all of these questions out, then see if you can formulate a broader question that encapsulates all of these smaller questions.

Identify why your research is important. Do this for academics both inside and outside your field, even if the position you’re applying for is in your field of study. Additionally, expect your audience to have a basic understanding of your field, but don't assume they will be an expert in a particular discipline. This might includes ways that your research can be applied to future problems or simply how your research addresses a knowledge gap in your field. For example, if your work is on x-ray technology, describe how your research has filled any knowledge gaps in your field, as well as how it could be applied to x-ray machines in hospitals. It’s important to be able to articulate why your research should matter to people who don’t study what you study to generate interest in your research outside your field. This is very helpful when you go to apply for grants for future research.

Describe what your future research interests are. The reviewers who read your statement don’t just want to know what you’ve researched in the past; they also want to know what you plan to research if they give you the job or fellowship you’re applying for. Think about what new questions you would like this research to answer or what new elements of your topic you’d like to explore. Explain why these are the things you want to research next. Do your best to link your prior research to what you hope to study in the future. This will help give your reviewer a deeper sense of what motivates your research and why it matters.

Think of examples of challenges or problems you’ve solved. These can be questions that your previous research has answered or problems that have emerged during the course of your research that you had to work around. This will serve not only to demonstrate your problem-solving abilities, but also to highlight how your past research has been successful. For example, if your research was historical and the documents you needed to answer your question didn’t exist, describe how you managed to pursue your research agenda using other types of documents.

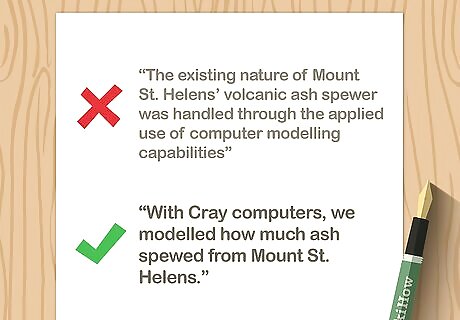

List the relevant skills you can use at the institution you’re applying to. Mention these skills throughout your research statement and describe how you were able to use them to achieve a goal. This will help the committee assess how compatible you are with the research undertaken at the institution and how likely you are to succeed in the future. Some skills you might be able to highlight include experience working with digital archives, knowledge of a foreign language, or the ability to work collaboratively. When you're describing your skills, use specific, action-oriented words, rather than just personality traits. For example, you might write "speak Spanish" or "handled digital files." Don’t be modest about describing your skills. You want your research statement to impress whoever is reading it.

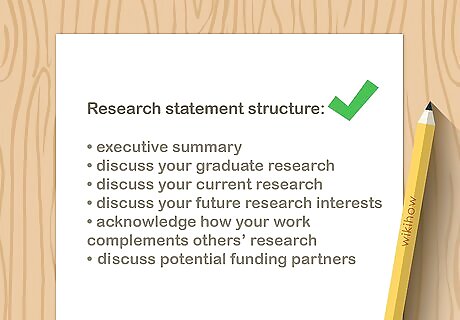

Structuring and Writing the Statement

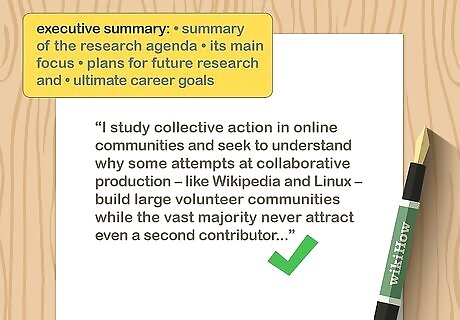

Put an executive summary in the first section. Write 1-2 paragraphs that include a summary of your research agenda and its main focus, any publications you have, your plans for future research, and your ultimate career goals. Place these paragraphs at the very beginning of your research statement. Treat this section as a concise summary of the things you plan to talk about in the rest of the statement. Because this section summarizes the rest of your research statement, you may want to write the executive summary after you’ve written the other sections first. Write your executive summary so that if the reviewer chooses to only read this section instead of your whole statement, they will still learn everything they need to know about you as an applicant. Make sure that you only include factual information that you can prove or demonstrate. Don't embellish or editorialize your experience to make it seem like it's more than it is.

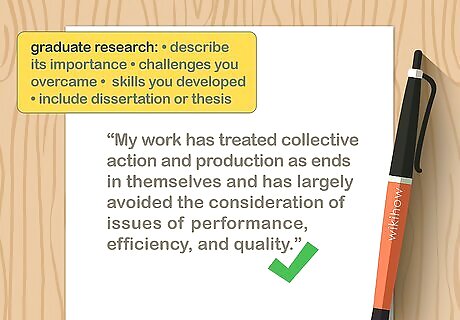

Describe your graduate research in the second section. Write 1-2 paragraphs that detail the specific research project or projects you did in graduate school, including your dissertation or thesis. Be sure to describe why your research was important, what challenges you overcame in carrying out this research, and what skills you developed as a result. If you received a postdoctoral fellowship, describe your postdoc research in this section as well. If at all possible, include research in this section that goes beyond just your thesis or dissertation. Your application will be much stronger if reviewers see you as a researcher in a more general sense than as just a student.

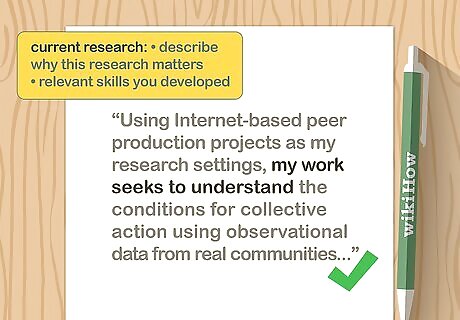

Discuss your current research projects in the third section. This is especially important if you’re applying for a position after you’ve already graduated from graduate school. Write about research you’ve carried out since your graduation to give the reviewers an image of you as a professional researcher. Again, as with the section on your graduate research, be sure to include a description of why this research matters and what relevant skills you bring to bear on it. If you’re still in graduate school, you can omit this section.

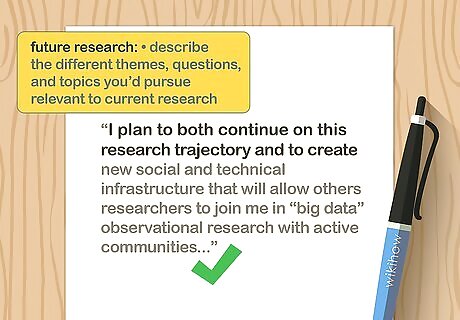

Write about your future research interests in the fourth section. Describe in 1 paragraph the different themes, questions, and topics you’d pursue in your research if your application is accepted. If you have multiple different projects you’re interested in pursuing, use more than 1 paragraph to make this section more organized. Be realistic in describing your future research projects. Don’t describe potential projects or interests that are extremely different from your current projects. If all of your research to this point has been on the American civil war, future research projects in microbiology will sound very farfetched.

Acknowledge how your work complements others’ research. Take every opportunity you can in your research statement to point out areas where the work being done at the institution you’re applying to is similar to your own research. This will indicate to your reviewers that you’ve researched the institution and you’ve actually thought about your future there. For example, add a sentence that says “Dr. Jameson’s work on the study of slavery in colonial Georgia has served as an inspiration for my own work on slavery in South Carolina. I would welcome the opportunity to be able to collaborate with her on future research projects.”

Discuss potential funding partners in your research statement. Talk about the different research grants, fellowships, and other sources of funding that you could apply for during your tenure with the institution. This will help the committee to see the value that you’d bring to the institution if they hired you. For example, if your research focuses on the history of Philadelphia, add a sentence to the paragraph on your future research projects that says, “I believe based on my work that I would be a very strong candidate to receive a Balch Fellowship from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.” If you’ve received funding for your research in the past, mention this as well.

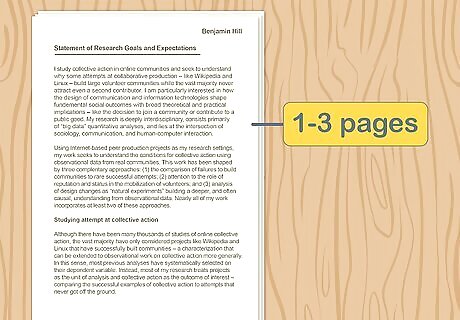

Aim to keep your research statement to about 2 pages. It’s okay if your statement is closer to 1 page or 3 pages, so long as it isn’t too short or too long. If you can’t fit everything you’re trying to say to around 2 pages, cut some of the less important sections or use more concise language. Typically, your research statement should be about 1-2 pages long if you're applying for a humanities or social sciences position. For a position in psychology or the hard sciences, your research statement may be 3-4 pages long. Although you may think that having a longer research statement makes you seem more impressive, it’s more important that the reviewer actually read the statement. If it seems too long, they may just skip it, which will hurt your application.

Formatting and Editing

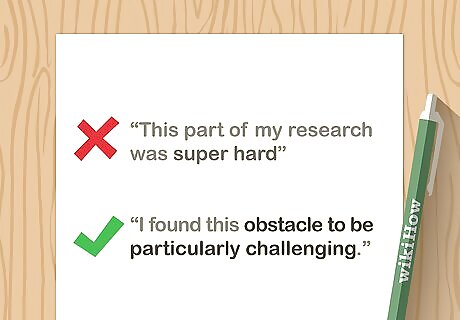

Maintain a polite and formal tone throughout the statement. Use language and phrases that you would use in a formal setting and that speaks to your professionalism. Remember, the people reading your statement are assessing you as a job candidate. For example, instead of saying, “This part of my research was super hard,” say, “I found this obstacle to be particularly challenging.”

Avoid using technical jargon when writing the statement. Write your statement so that a person outside your field can understand your research projects and interests as well as someone in your field can. The reviewer can’t get excited about your research if they can’t understand what it’s about! For example, if your research is primarily in anthropology, refrain from using phrases like “Gini coefficient” or “moiety.” Only use phrases that someone in a different field would probably be familiar with, such as “cultural construct,” “egalitarian,” or “social division.” If you have trusted friends or colleagues in fields other than your own, ask them to read your statement for you to make sure you don’t use any words or concepts that they can’t understand.

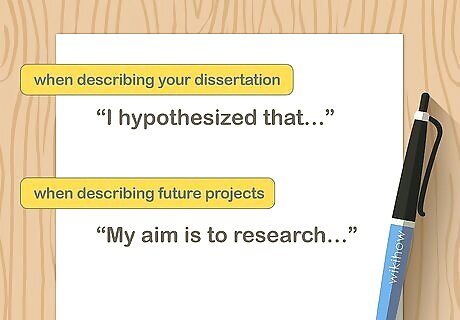

Write in present tense, except when you’re describing your past work. Use present verb tense to talk about your current and future research projects, potential collaborators, and potential sources of funding. Only write in the past tense when you’re writing about research and accomplishments that actually took place in the past. For example, when describing your dissertation, say, “I hypothesized that…” When describing your future research projects, say, “I intend to…” or “My aim is to research…”

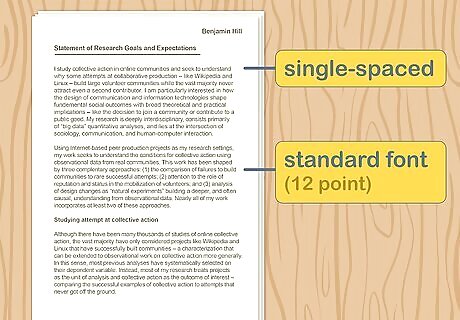

Use single spacing and 11- or 12-point font. Since your research statement is fairly short, there's no need to double-space the text. If your statement is physically difficult to read because of a very small font, the reviewer may develop negative feelings towards it and thus towards your entire application. At the same time, don’t make your font too big. If you write your research statement in a font larger than 12, you run the risk of appearing unprofessional.

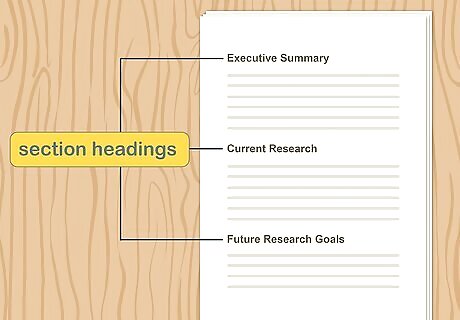

Use section headings to organize your statement. Use descriptive headings like “Current Research,” “Future Research Projects,” and so on that delineate the different sections you used to structure your research statement. If any of your sections are particularly long, consider using subheadings within these sections to make your statement even more organized. For instance, if you completed a postdoc, use subheadings in the section on previous research experience to delineate the research you did in graduate school and the research you did during your fellowship.

Proofread your research statement thoroughly before submitting it. Even if your research sounds very impressive, a spelling error or grammatical mistake on your research statement can seriously undercut your application. Have a friend read over your statement for you to make sure you haven’t overlooked any simple mistakes.

Comments

0 comment