views

Preparing to Develop Your Theme

Understand the difference between "subject" and "theme." "Subject" is a more general term than "theme." In non-fiction, the subject is a general topic of interest, while in fiction, the subject is some aspect of the human condition explored within the work. A theme is an explicit or implicit statement about the subject. As a non-fiction example, a white paper could have as its subject be the improvement of the security of the cargo transportation supply chain. Its theme would be the forms of business data and means to access it that could provide those improvements. As a fiction example, the Hans Christian Anderson story, "The Ugly Duckling," has a subject of alienation in that the main character is depicted as different from his peers. The themes, however, are themes of failure to fit in, as well as self-discovery as the "duckling" grows up to discover he was actually a swan.

Identify the purpose of your writing. The purpose behind your writing will shape how you develop your theme in the piece. There are numerous purposes as to why someone writes. Your writing may serve any of these purposes (or any combination thereof): Documenting or recording an event or information Reflection on an idea Demonstration of knowledge Summary of information Explanation of an idea Analysis of a problem Persuasion Theorization that speculates or seeks to explain an issue Entertainment

Identify your audience. Understanding who your audience is lets you determine which themes are appropriate to your audience. This will also help you identify how best to present those themes to your audience. You can determine what themes are appropriate to your audience by realistically assessing how much knowledge and experience the audience has. For example, in a business marketing letter, your audience will be prospective customers. Your purpose is to inform or persuade them to buy, and your theme might be to show them how your product will meet their needs. You may include statements of needs your customer will identify with, and then follow each statement with a short paragraph about how your product relates to that need. Dr. Seuss wrote books for young children, requiring him to use a limited vocabulary. His "The Star-Bellied Sneetches" had a theme of learning to accept differences. In the story, the Sneetches learn to accept differences after applying and removing their belly stars so many times that they no longer remember their original appearances. In telling the story, Seuss used short words, made up words, and wrote in a distinctive rhyming cadence that made his words. This helps the reader recognize and remember the lessons behind them.

Consider the length of what you're writing. Longer works, such as novels or memoirs, permit the inclusion of other themes subordinate to the primary theme of your work. In contrast, shorter works, such as short stories or editorials, usually have room to address only a single theme, although they may give passing reference to supporting ideas.

Defining Your Theme

Make an outline of your story. Most stories start with a kernel of an idea. This may hint at the theme of your story, or the theme may emerge through the development of the story. If you have an idea for a story, it will be helpful to sketch out the story. Then you can start to determine the different directions it can take. This then points to potential themes that you can focus on. Outline your story, listing the characters and setting out the order of events that will happen in the story. EXPERT TIP Grant Faulkner, MA Grant Faulkner, MA Professional Writer Grant Faulkner is the Executive Director of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and the co-founder of 100 Word Story, a literary magazine. Grant has published two books on writing and has been published in The New York Times and Writer’s Digest. He co-hosts Write-minded, a weekly podcast on writing and publishing, and has a M.A. in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. Grant Faulkner, MA Grant Faulkner, MA Professional Writer The best themes emerge from the story and aren't grafted there. You can develop a strong theme by merely writing your story and allowing the theme to emerge from your words on its own instead of forcing one into the story.

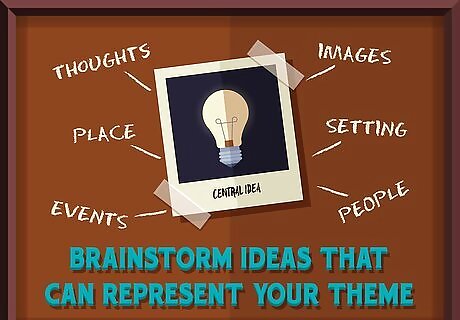

Brainstorm ideas that can represent your theme. Once you’ve identified a theme for your story, you can start to think about ways in which to represent that theme. Start with a free association exercise. In this exercise, focus on your theme – either the word or phrase (such as “family” or “environment” or “corporate greed”). Let your mind wander and observe the thoughts, people, images and so on that enter into your mind. Write down these thoughts and images. Try out the technique of “mind-mapping”. In this technique, you start with a central idea and begin to map out the ways in which the story develops. This way, you can also start to identify how the theme weaves through the story.

Look into your character’s motivations. Your story’s characters are tasked with goals and aspirations. These motivations drive your character to act certain ways. These actions often feed into your theme. For example, if your character is passionate about becoming a vegan, you might start to examine themes of whether humans have the right to take control over the natural world. In many non-fiction pieces, such as a letter to the editor, you are the “character” and your motivation is what will define the theme. For example, if you are writing a letter to your congressperson about a recent oil spill in your community, your theme could be something like the need for environmental cleanup and responsibility.

Think about your story’s conflict. The characters in your story are faced with a conflict that drives the plot. This may be an event or an antagonist. When you figure out the central conflict of your story, you may start to uncover your theme. For example, your character’s parent committed a crime. Your character, a police officer, is faced with a moral dilemma of whether to arrest the parent or not. Your theme could start to emerge from this conflict.

Research to support your theme. Research is important in both non-fiction and fiction. In non-fiction, you are primarily looking for facts to support your theme and the points supporting it. In fiction, research also feeds into making your characters and the environment in which they interact as realistic as possible.

Realize that you can have more than one theme. There isn’t any rule that says you can only have one theme. You may have a dominant theme with sub-themes that strengthen and deepen your thematic dimension. For example, perhaps your dominant theme is the human impact on the environment, and you have sub-themes of corporate greed and the breakdown of community in modern society.

Weaving Your Theme into Your Writing

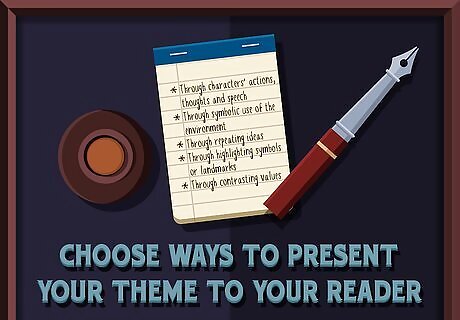

Choose ways to present your theme to your reader. A solidly presented theme will emerge through many different facets of your story. Start thinking about how your theme will become apparent to your readers. Some of these ways include: Through characters’ actions, thoughts and speech Through symbolic use of the environment Through repeating ideas Through highlighting symbols or landmarks Through contrasting values

Use narration to present facts and details. Narration means to present facts and details in an organized, usually chronological fashion to tell what happened and who it happened to. Narration is used in most newspaper articles and commonly in stories told in the first person.

Use description to build an image in the reader’s mind. Description is the use of words that invoke the senses to build an image in the reader's mind of the item being described. Description is particularly powerful in fiction as a substitute for narration. Instead of writing that a character was angry, you describe the character as having bulging eyes, flared nostrils, and a beet-red face, and use "thundered," "shouted," or "screamed" in place of "said" to describe the character's voice.

Use the tool of comparison and contrast. Comparison is showing the similarities of two or more things. Contrast is showing the differences between two or more things. Comparison and contrast can be used in both fiction and non-fiction. For example, comparison and contrast was used to describe the lifestyles of the protagonists in Mark Twain's "The Prince and the Pauper." It can also be used for a side-by-side comparison of laptop computer features.

Try an analogy. A form of comparison and contrast, the analogy compares something familiar to something unfamiliar to explain the unfamiliar item. An example of an analogy is comparing Earth’s size in the universe as a grain of sand.

Incorporate symbolism into your story. Symbolism is using something to represent something else, such as the storm gathering around Roderick Usher's house in Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher." This represents Usher's own disquiet after his sister's burial. Symbolism is more common in fiction than non-fiction and requires the reader to be familiar with the symbols you use and their intended meaning. Try a recurring motif to institute symbolism in your story. You might have a recurring motif or detail of a person singing “Ave Maria” in your story.

Finalizing Your Theme

Get feedback. Allow lots of people read your writing. It is helpful to get other eyes on a piece of writing so that you know whether your ideas are conveyed clearly. Ask these readers about their impressions. See if they can identify your theme without prompting. Be open to the ways that other people respond to your writing. They might be able to point out errors that you regularly make, which can help clarify and improve your writing. They might also ask thought-provoking questions that helps you consider an angle you hadn’t previously considered. Remember that this feedback is not intended to be personal; they are responding to the writing, not to you.

Put away your writing for a few days. Get some distance from your writing by putting it away for a bit. Sometimes when we write, we’re so invested in the story and shaping the words that we lose sight of the bigger picture. Take a break from your writing by turning your focus to a different project for a few days. Then come back to your writing and reread it.

Make changes to your theme. Based on your own evaluation of the piece, as well as the feedback you’ve solicited from others, make alterations to your theme. You may recognize that, while you thought your theme was one aspect, your readers interpreted it very differently. For example, perhaps you have been focusing your theme on a firefighter’s triumph over her parents’ disapproval. But then you realize that your story is really about the firefighter’s struggle in a male-dominated profession. A change to your theme might necessitate adding or deleting some passages that do not strengthen your theme.

Comments

0 comment