views

Was Sahara’s $ 370 million bid for the Pune Indian Premier League (IPL) team too high? The buzz around the IPL valuations has varied from a layman’s perspective -- this is too much money! -- to that of a conventional financial analyst -- so what are the forward multiples looking like? Both are equally simplistic.

So why would anyone want to pay so much money for a cricket team? Aren't the first eight IPL teams in losses after forking out so much?

The answer: Sports teams are valued differently from normal businesses, and financial parameters are not the only factors to be considered. There are the emotional variables such as the trophy value attached to the location or team, the number of prospective buyers with a personal or professional link to the location, and in a broader sense, the scarcity premium. All of these vary quite drastically in the eye of the beholder.

When Vijay Mallya bought the Bangalore franchise, that acquisition could be compared to the hypothetical purchase of a heritage palace in Mysore by a buyer. Grand as it looks, the palace isn’t a convenient permanent home. Government regulations forbid rentals or conversion to a hotel. But the buyer’s motivations go beyond a simple return on investment. Maybe he wants to market his (or his company’s) image. His palace can easily host parties for hundreds of guests, it is featured frequently in global media and tourists flock to the adjoining palace museum -- and maybe it is minutes away from the village where the buyer grew up. And there are only 10 palaces still surviving.

The buyer knows that he could make substantial profits if he were to sell the palace in five years hence -- there’s a new Indian billionaire every month -- and the world’s going to be interested in getting a piece of the India action too.

So that’s why an IPL team makes sense.

Add some attractive financials to the picture, and you’ll see why IPL franchisees are at the receiving end of some tempting offers for their teams. At least seven IPL teams will record a profit in IPL 3 -- compare that with the 18-year-old English Premier League (EPL), where only 11 teams out of 20 registered an operating profit in 2008, and after the downturn, that dropped to seven.

When the IPL was designed, the structures of international leagues such as the EPL, National Basketball Association (NBA), and National Football League (NFL) were studied. The aim was to arrive at a customised model that would meet both sporting and financial objectives.

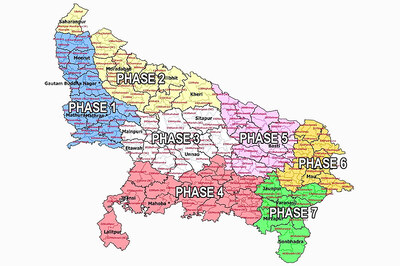

The graphic highlights how the IPL is designed for better financial viability. A key factor is also the way that team owners pay for their ownership rights. The IPL model has ensured that team owners pay only 10 per cent of their purchase every year for 10 years.

If a team owner has bought an IPL team for $ 100 million, today his only outgo is a cash flow cost of about $ 300 thousand annually. That’s the cost of borrowing $ 10 million at 18 per cent for two months — and at the end of each season, he’ll be able to repay his short-term loan quite easily. So for all the initial owners, that’s quite a sweet deal for an asset worth upwards of $ 200 million.

I’ve sometimes been asked if we gave these teams away too cheaply, and the answer is a definite no. Remember, we only got 10 valid bidders for the first eight teams. The successful bidders had taken a contrarian stance against the prevailing risk or return perceptions of the IPL -- and have earned super-normal profits simply because reality turned out to be far ahead of those perceptions. A look at the extreme end of this story: Google’s valued at $ 179 billion today but nobody grudges those two college professors who put in that first $ 200,000 at a valuation way below $ 10 million.

In this context, the $ 370 million Pune bid is not surprising. In the second round, investors had clear visibility on the success of the IPL, and the demand for teams. A 300 percent valuation increase is reasonable at Stage 2 funding of a quality start-up, leave alone one as wildly successful as the IPL.

These latter two teams will have annual costs that are an average of $ 26 million higher -- which probably means that they could take four or five years to reach profitability, compared to a maximum of three years for the others.

The future road to riches

But revenues haven’t plateaued yet. In addition to revenue growth from sponsorship, licensing and merchandising, etc., there are new business opportunities that could at least be profit accelerators if not multipliers. Some of them might seem improbable, but isn’t that how the IPL was perceived to be in November 2007?

Club IPL

Imagine watching the IPL at the stadium -- in your plush sofa in a lounge environment, with a few of your business associates for company. You’re enjoying the game, and also the Brunello di Montalcino and Fontina served to you. A gourmet dinner and an after-party follow. The kids have managed to meet some stars. Your experience at Club IPL starts with the limousine pick-up and ends with the exclusive merchandise -- and your firm has a corporate box for five seasons. Unlikely? Maybe, but not impossible.

The number of premium seats depends on the catchment area demand and the stadium capacity. There would be capex involved here, but payback in the first year is not unrealistic. A sensible sales strategy would be to allow some time for scarcity premium to set in before selling corporate boxes for three to five years. Club IPL should, on the average, have about 2,000 premium seats per stadium that could yield revenues of at least Rs 50-75 crore annually. A shared investment or returns arrangement between the stadium owner and franchisee would work best.

IPL anywhere

The biggest growth opportunity for cricket is its adoption by new markets such as the Americas, Europe, and maybe even China, in terms of the development of teams as well as mainstream television audiences. In these markets, where the primary sports have games of less than two hours’ duration, T20 is the only way cricket can be evangelised successfully. A smaller version of the IPL could visit at different times of the year, with perhaps three to five IPL teams and a local national team taking part in a league. Sponsorship and media revenues from the regular cricketing nations would dominate, while local revenues would grow over time. While short-term revenues wouldn’t be negligible, the primary benefit would be the long-term growth of the IPL, global team fan bases, as well as cricket in general.

Similar mini-leagues in UK, Australia, UAE would be another opportunity, where gate revenues along with media revenues from India and the host country, could mean anywhere around Rs. 200 crore a year accruing to IPL.

IPL royale

Cricket-related betting is an illegal sector estimated at around Rs 160,000 crore annually. We know that it’s linked to match-fixing, and enormous amounts of black-money, but burying our collective head in the sand seems to be the response.

The best way to combat this would be for the government and the BCCI to partner on a legal betting platform, starting with the IPL. Licensing out the betting operations to perhaps two independent entities would work best for competency and credibility.

A countrywide distribution network is required, allowing bets to be placed anonymously in cash, and winnings collected similarly after tax. Access through the fixed and mobile Internet, and other payment options such as credit or debit cards would help.

If the legal IPL betting platform gets even 20 per cent of the illegal market in two years, that amounts to above Rs. 30,000 crore. Costs include winner payouts of about 30 per cent and betting licensees’ commission of around 5 per cent. After deducting a BCCI partner fee of say, 15 per cent of profits, that leaves the government with close to Rs 18,000 crore. In social development terms, this could double the planned Central outlay on healthcare, or on the Right to Education Act! Currently, the government gets about Rs 200 crore from the IPL, through taxes.

Assuming a franchisee-BCCI share of 60-40, this means that the franchisees would get about Rs 180 crore each, all straight to the bottom-line. In closing, are revenues bad?

In India, revenues made by the “purer” sectors are not normally received well — whether in education, healthcare or sport.

It is very likely that, one day, IPL revenues will subsidise and help preserve Test cricket, and maybe other sports in India too. Ask any sportsman, official, viewer or spectator linked to some of the other sports in India, if they would like their national sports ecosystem to be in a similar position, and see what they say.

(The author is co-founder of the Morpheus Media Fund, and was earlier managing director of IMG India, where he was involved in designing different aspects of the IPL. )

Comments

0 comment