views

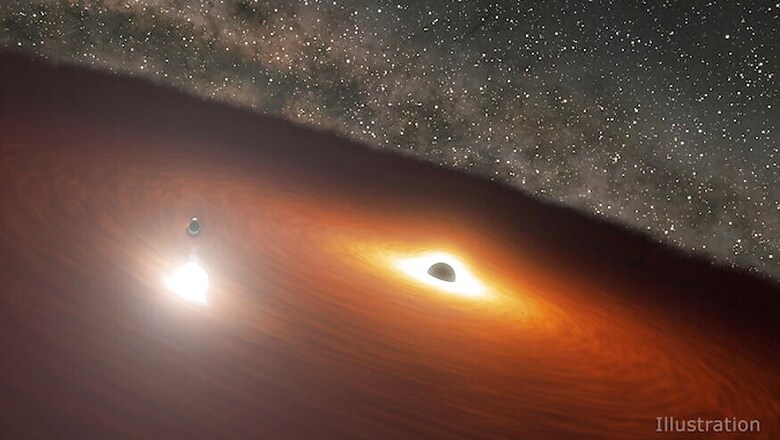

In a galaxy far, far away, two black holes share a unique relationship. While a single black hole is enigmatic enough, the OJ 287 galaxy, which is 3.5 billion years away from Earth, has TWO black holes that 'dance' around each other — linked by relative gravitational interactions. The main black hole at the centre of this system is one of the largest ever dying stars ever observed by us, and carries a staggering mass of 18 billion times that of our Sun. Around the central black hole, orbits a 'puny' black hole that is 120x smaller than the behemoth at the centre. This too, however, is 150 million times the mass of our Sun. Now, an group of Indian scientists at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai have contributed to creating the most accurate model of predicting how the two black holes react to each other.

The sight is super rare, and so far, the only one of its kind that we have seen so far. The central black hole exerts an incredible amount of gravitational force around its periphery, and also has enormous gas discs surrounding it. Every 12 years, the smaller black hole crashes through these discs twice in irregular intervals. The resultant is a flash of light that is brighter than the peak brightness of over one trillion stars. In fact, the forces of the behemoth black hole at the centre is so gargantuan that the orbit of the smaller black hole changes with completion of every circle. It is this that raises curiosity regarding the binary system, and a fortuitous observation made by Spitzer, the now-retired legendary NASA space telescope, is to be largely thanked for it.

On July 31, which is when the team of TIFR scientists had predicted the next collision of the black hole dance to happen, the OJ 287 system appeared to be situated on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth, or behind it. This made it impossible for any telescope on ground or in Earth's orbit to observe OJ 287's supposed clash. The scientists were attempting to better the model of studying binary black hole interactions, and their new model had claimed to be accurate to within four hours of the collision observation point. Luckily, in came an old friend to the rescue.

Spitzer, which happened to be at 254 million kilometres away from Earth on July 31, 2019, was the only object accessible to mankind with a vantage point to view OJ 287. Fortuitously, the observations made proved that scientist Lankeswar Dey and his TIFR team's model was indeed accurate. This gives mankind's space research a new capability, and will help better understand how gravitational waves can alter trajectories of bodies in outer space. It further lends information to research around the surface of black holes, giving us a conclusion that at least our basic understanding of black holes is roughly on point.

The incredible interaction has been illustrated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and can be seen in the cover image above (click to expand). Safe to say, this is about the most incredible image that you would see today.

Comments

0 comment