views

New Delhi: Demonetisation has hit the vegetable market severely - right from the farmer unable to sell all his produce to wholesalers with similar woes and finally, vendors who say that the cash crunch has impacted their sales too. But if most of those in the supply chain are buying and selling at rates that are considerably lower, why is it that the price you are paying for your vegetables hasn't fallen?

To understand why, let's take a look at every link in the chain.

STEP 1: THE FARMER

Ganesh Pal Singh travelled close to 250 kilometres to sell his produce at one of Delhi's largest vegetable wholesale markets, the Ghazipur Mandi. His tryst with demonetisation has not gone well so far.

"I have been here for 3 days now, unable to sell the sacks of chillies I brought along. What sold at a rate of 10 to 12 rupees a kilo is now going at 5 to 6 rupees. Despite selling it at half the rate, we are not able to sell more than half our produce."

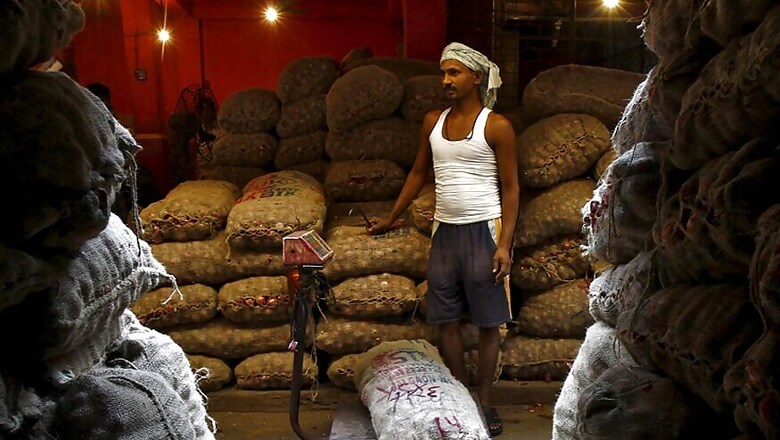

STEP 2: THE WHOLESALER

Sachin Kumar Gupta is a wholesaler at the Ghazipur Mandi. He explains why his stock is limited this demonetisation season. "For the past 8 days, I have not asked for any produce to be transported from the villages. Neither can I pay the farmers nor can I afford the freight charges. I simply don't have enough of the new notes that both farmers and transporters are demanding."

STEP 3: THE LOCAL VENDOR

Nanduram sells his vegetables off a cart parked outside Mayur Vihar's residential complexes. His fare too has gone down over the past few weeks. "People come and offer to pay in old notes. Even if i do accept them, those I buy from at the mandi don't. Going to the bank to deposit and then withdraw the money too has become such a cumbersome process. The number of people buying from us and the amount they buy has gone down. The rates we are selling at has stayed the same."

But if the rates at which the sale of vegetables are taking place has taken a severe hit along the length of the supply chain, why is that cut in prices not being transferred to the end consumer?

Gupta explains from a wholesaler's perspective. "The vegetable vendor who previously had enough cash to buy ten cartons of groceries now can only muster the money for a couple of cartons. The vendor's sales too have been affected drastically. How is he expected to make two ends meet if he reduces his selling price? The only way he can compensate his losses, to some extent at least, is by keeping the end price for the consumer the same as it was pre-demonetisation."

Every step in the supply chain, from the farmer to the wholesaler to your vendor, is reeling from the losses suffered post the note ban. And even as their businesses stay bleak, keeping the final price of vegetables stable seems the solitary option for recovering some of the losses incurred. So maybe it's not such a bad thing after all.

Comments

0 comment