views

To many, in fact most, tiger estimation or census is about knowing a number - the final count of a majestic beast, the sight of which inspires awe in unlimited measure but the existence of which lies in the hands of the Homo Sapiens.

However, very little does the society in general know about the conservationists who not only bring out the tiger numbers but are also the tiger's only hope for thriving in the wild.

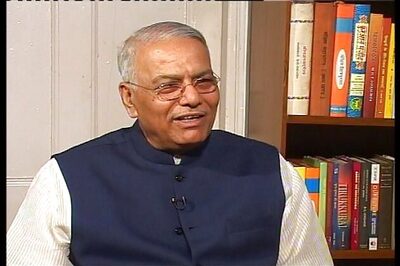

Searching for the answers, the author travelled to the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in Dehradun where a team of research biologists, led by eminent wildlife scientist Dr. Yadvendradev Jhala, is working day in and day out to collect data from the forests across India and then analyse it in the laboratory at WII to arrive at the much-awaited tiger numbers.

Dr. Jhala has been a pioneer in the field of tiger conservation and one of the key men who not only devised the scientific methodology of estimating tigers but also implemented it across the 500,000 sq km of forest across India. And he was kind enough to explain to the author about tiger estimation and where we need to go from here in terms of the beautiful beast's conservation.

Let's start with an interesting bit of information we dug out about you, Dr. Jhala, that as a child you wanted to be a zookeeper. How did this happen?

I always had passion for animals, and as a kid I didn't know there was something like wildlife science. The closest you could get to a wild animal was in a zoo. So while in kindergarten, I wanted to be a zookeeper. And I think I have lived my dream and done better than that actually.

Sure you have. But not many get to do what they love and earn a living out of it.

I think it was encouragement from my parents. They allowed me to pursue my dream. My mother was keen that I go into medicine. I tried that and got into a medical college, but then realised that's not what I wanted to do. So they allowed me to change and switch to zoology instead.

But was there an inspiration during your childhood?

My father was inspirational. He was always a conservationist. We used to have a farm, see wildlife and that's how it started.

You have taught wildlife conservation and management throughout the world. Where do you think India stands in comparison to the rest of the world?

I would say [India is] one of the top places where wildlife conservation and wildlife science have been promoted. I would not rate India second to any other country. The legislation that we have for conservation is probably the strongest anywhere in the world, and people's awareness is also very high.

What we lacked, in my case, was a formal education system for training people in wildlife science. But now we have that as well in many of the institutions in our country.

You head the genetics laboratory here at WII? What does that job entail??

The genetics laboratory is not something that's my primary passion. It is sort of means to an end. Initially, still actually, India is very strict in exporting biological samples outside the country. So we had to develop our own facilities here. I used to work earlier with the Smithsonian. I had good friends and collaborators there. So we set up a facility to do that somewhere in the late '90s in India itself. I was working on wolves at that time. We discovered that the Indian wolves are ancestral to probably all the wolves in the world. They are about a million years old lineages in India than you have elsewhere.

You have also been involved with ecology and monitoring of tigers, which has become your primary work area now. Tell us something about that.

When Dr. Rajesh Gopal took over as Project tiger Director way back in 2001-02, he approached us, me and my colleague Qamar Qureshi, to help him develop an objective way of estimating tiger population. So we started work with him in the Satpura Maikal Landscape. We were developing something based on indices and a double-sampling approach where you have large-scale samples coming in the form of indices and then a part of it being intensively sampled for mark-recapture statistical and robust estimates and then calibrating the indices versus those estimates.

We had this system going. Meanwhile in 2005, Sariska happened; we had (tiger) extinction crisis. The Prime Minister of India then appointed a Tiger Task Force. So the Tiger Task Force was looking at the estimation of tiger population, how to actually have an objective way of assessing whether we have increasing tigers or decreasing tigers, and look at conservation investments, whether they were having the desired results or not. They really liked it at that point in time, so they asked us to apply it across the country. So from a 50,000 sq km area, we started applying to about 500,000 sq km. That's how it all started.

When Sariska happened, the reintroduction of tigers over there was the first of its kind in supposedly the world. How different or difficult was it?

Re-introducing tigers into a habitat that is vacant is probably one of the easiest things to do, but it had never been done before. If you take a captive animal and put it back in the wild, it's a different thing. But here the tigers were taken from wild to wild. There were wild tigers taken into an empty habitat, which had good prey population and good area of forest. The problem here was that there were still many villages inside Sariska, and these needed to be relocated. That took a lot of time. That's still happening. It's not achieved its 100 per cent goal, which was desired or which was committed by the state government. But they are in the process of achieving it. So I don't think it was a very difficult task, but it was just that it was never done, had no precedence to follow.

It was something that the government of India couldn't afford to fail in, because the whole world was looking at us.

I want to quote one line from one of your published interviews: "The problem is the lack of professionalism and ethics in reporting the results of pugmark enumeration, not so much the method." Can you throw some light on that.

India was counting its carnivores, lions and tigers, when the world did not have a method; and this was based on the traditional shikar (hunting) system, where the shikaris (hunters) were actually very good field trackers and could identify different animals based on the pugmarks. So this system, if you are an expert, works well with a few animals. But what happened was that this was taken away from field craft to more sort of a route-based analysis, where you would have pugmark casts and tracings coming, put into a room, and an expert from somewhere would come and look at these and say how many tigers there are.

Now that is impossible to do. You need to know, in the field, where these tigers are operating. So if a person is working in the field, has been tracking the tigers regularly and looks for idiosyncrasies in the pugmarks, the type of gait, how the pug falls, how the stride is, then you can identify individuals. So it went from something which was a field craft to something which couldn't be possibly achieved. Also it gave a lot of way to manipulate data.

So in Sariska, when the tigers were actually extinct, the official estimate was about 18 tigers present there based on the records. But that was impossible because there were no tigers. It was fudging basically. So the ethics of reporting numbers is very important. You can fudge any kind of data. That was the major problem, and the pugmark lent itself to manipulation.

Since you have been involved with tiger estimation and the scientific methodology that was introduced in 2006, your are doing it for the third time this year, can you explain that process in brief?

We have about 500,000 sq km of forest habitat, which is potential tiger habitat, in 18 states. It's impossible to cover all these forests by wildlife biologists and using camera traps. So we used the huge manpower available with the forest department to actually sample every beat in these forests - be it a national park, sanctuary, reserve forest, protected forest, all the categories of forests were actually sampled at a beat level.

A beat is about 20 sq km. So in every beat you set a forest guard and a casual labourer to look whether that beat has tiger signs or not. If you get a pugmark or a tiger scat, you know there are tigers, and this is done in replicable format in a statistical manner. So you can actually find out that in some areas where you do not find signs and other factors are favourable - in the sense there is wild prey, there is good forest, less human disturbance, then the chances are they don't detect a tiger sign. So this method allows you to look for non-detections. That's called an occupancy framework, which is done across the country.

Once we have this information, then we send in a team of research biologists in certain areas, and there we put in cameras and we take remote pictures of tigers, so tigers take their self-portraits.

So what we see is, suppose in a beat a forest guard walks 10 km and he finds 5 or 10 tiger pugmarks and another forest guard in another beat finds only one pugmark, then obviously you know there are more tigers in the first beat than in the second, but we don't know how much more. This is now calibrated with camera traps. So if you have density of, let's say, five tigers in the first place and two in the other place, then you know two tigers translate into two pugmarks while five tigers translate into 20 pugmarks. So that relationship is established across a spectrum of densities.

Associate variables like prey availability, their densities, human impact on the habitat, type of forest cover there is, the size of the forest, how far is it away from urban centres, what is livestock density, these are all ancillary variables which determine the number of tigers. So they are all used in a multi-dimensional, multi-variant analysis; and we come up with the tiger status across the country.

We are doing the analysis here [at WII]. It's a humongous effort. We have about 44,000 people working for us in collecting this data for about 10 days across the country. So it's a huge effort. Probably nowhere in the world such effort is put in for doing wildlife census.

Are there any upper and lower limits of tiger estimation

We do not know how many tigers there are. It's impossible to know whether there are 1411 or 1706. It's just the midpoint of our estimate. So we have the upper and lower limit on our estimates. The tigers in the country are somewhere within those limits. But the probability is that they are somewhere in the middle. The exact number of tigers is impossible to know.

How are the upper and lower limits decided?

What happens is we actually predict the densities of tigers at a 100 sq km grid, 10 x 10 grid, which the size of a home range of the tiger. So the prediction for those grids is quite precise. Over time, we can actually look at whether these density figures are changing or not. So that's how we monitor the status of the tigers. But there are several grids that have zeroes, no tigers at all. So when you take an average of everything, the variability across the landscape becomes very large. So our confidence limits of talking about the upper and lower limits are quite large for the entire country. But site-specific grids are very specific. That's what is used for monitoring trends across time.

But we need an estimate because the Indian public as well as politicians don't understand that there are limits and site-specific densities, so you need to give a number, which is an amalgamation of all this put together with limits on it.

Phase IV, which is camera-trapping the tigers throughout the year, is a continuous process.

The issue is that the countrywide assessment is every four years. But tigers, as you know, are prone to poaching because there's a huge market out there, illegal markets in China and South-East Asia. So one could deplete the breeding population of the tigers, which is known as the source population, very rapidly if poaching occurs. So within four years, you could lose tigers. So the important key populations in tiger reserves are monitored on an annual basis through camera traps, that is what is called Phase IV.

Also, we monitor the prey because without prey you can't have tigers. So we monitor prey by using distance sampling methods which are also statistically highly robust methods. Both these techniques are used on an annual basis, so we keep a tab on the pulse of the population.

There's something called online tracking system for poaching being devised. How is it done?

It is a patrolling system, which is called M-STRIPES. It's a short form for Monitoring Tigers with Intensive Patrolling and Ecological Status. This is a GPS-based patrolling system.

Earlier what was happening that a guard would say I patrolled my beat, but there was no way to prove it. He could be sitting at a tea shop but report to his seniors that he has done his work. Now what we have devised is that he moves around using a GPS, put a track log and he walks around his beat, patrols it. And wherever he encounters an illegal activity, he records it with GPS and takes a photograph which is geo-tagged. If he sees animals, he records their presence as well. So if he sees a tiger or a tiger pugmark, he records it with GPS. In the evening when he comes back, he downloads it into a software system.

So within a week to 10 days, if the park manager wants to know which areas of his park have been patrolled to design the next beats patrolling, he knows that okay this is where the patrol has [already] happened. You can't fake this. There is a GPS associated with this. There is a track-log on this. So you know exactly which areas have been patrolled and which are not, where illegal activities are occurring, where animal distributions are. So it's on a GIS, and that system is called M-STRIPES.

It also takes data from the tiger reserves done in the year based on the forest department's sign indices and analyses to let the park manager know if there are increasing trends in his animal population or declining trends at a very specific and special resolution of a beat. So if the tiger populations are depressed in a range over a three-month period, we don't see signs of tiger, it will show up as a red alert. We don't have to wait for a year, this is done on monthly basis.

Besides tiger monitoring, there are several other animal species and there could be chances that they remain uncounted. Is it true?

No it's not the case. We are using the tiger as an icon - because it attracts attention, funds and all that - but we are looking at the entire spectrum of the carnivores as well as the ungulates, the hoofed mammals, in all the tiger range states. So we have distribution and abundance estimates of all the species and they are generated as maps in our reports. So using the tiger as a flagship, we are actually monitoring the mammalian biodiversity of all these forests simultaneously.

You depend immensely on research biologists who face a lot of challenges and risks while collecting data in the forests. Tell us about them.

I believe that living in the forest is less risky than living in the city. The threats from people are far greater than you will ever have threats from animals, because animals are very afraid of human beings, all kinds of animals. So it's very rare that an animal will attack you. You need to be a little cautious about your environment when you are walking in the forest or doing sampling in the jungle. We train our researchers to take those precautions and we have not had any unfortunate experiences yet.

The only bad experiences we have had is that when some of our researchers were actually kidnapped by people in the northeast. Some of our collaborators working with us from the Worldwide Fund for Nature as well as some of our people working for the institute had some experiences with the extremists. Those are the issues one needs to be careful about. They are well trained actually in how to deal with animals, so that's not an issue.

What about the job opportunities for these researchers who work on fellowship otherwise?

The job opportunities are quite rare. We are hopeful that the Government of India will do something about it, in the sense that it is important that national parks, sanctuaries, tiger reserves have qualified wildlife biologists working with them. It would help a lot because you don't expect a forest officer to do everything, in the sense do research, do monitoring, patrolling, law enforcement, construction activity; there are a plethora of activities. If the science part of it was taken away and that responsibility is given to the wildlife biologists, I think they would do better science because they are the persons responsible for doing it, well trained.

And the responsibility will be much lesser on the [forest] department. They need to concentrate more on law enforcement, patrolling, the heart of conservation. Science and monitoring probably is about 10-15 per cent of what is required in conservation; the rest of the 80 per cent is protection and habitat management, which is the responsibility of the forest department. So the cadre of wildlife biologists working with tiger reserves, national parks and sanctuaries is where we need to go in the next decade.

My final question - a straight forward one. What do you think about the future of tiger in India?

I think if the tiger is going to survive, it's going to survive in India. We have the largest global population of tigers, close to about 60 per cent of wild tigers survive in India. The people's attitude towards conservation is far better in India than anywhere else in the world. We are very tolerant people. The tiger is an icon of our culture, our religion, and it's the biodiversity umbrella for the conservation of our forest. The government has done a lot to protect it, has declared tiger reserves.

The best thing which has happened for tiger conservation is to make inviolate space for tigers, the core areas of tiger reserves by voluntary, incentive-driven re-settlement of villages from inside tiger reserves. And I think that has given renewed hope to tigers. Where we need to go from now is to secure connectivity between these tiger reserves. Most of our tiger reserves are actually too small for long-term conservation unless they are connected and tigers can move between reserves. These are the corridors. So that's where we need to focus our attention and landscape scale conservation.

Tiger reserves are secure; their source populations are secure. But their long-term survival depends on gene flow between these populations, and that's what required by the government to take cognizance of the fact and develop land-use policies in such a way that the corridors which are existing today will not get lost tomorrow in our rapid necessity for development. Development is good, it is needed, but there are certain areas we need to restrict ourselves or to mitigate whatever impacts we may have. Mitigations costs a little more, only thing is it should be coming into the policy in the beginning of the planning process. We need to involve professionals who can tell what mitigation measures are required when we develop in the areas of corridors.

I don't think the forest cover is depleting, but the quality of the forest is changing. So from natural forests we are going towards artificial plantation. You may have the [forest] cover increasing over time, but what is required is the biodiversity value of this forest, and their ability to support the subsequent trophic levels. So forest size in India remains constant, because we are very strict, you cannot convert forest land to other land forms unless there is a whole process involved from the Government of India. That's a very strict process. But the pernicious chronic depletion of forest by biodegradation through human use, the extractive nature of our societies that live in the forest, is reducing the productivity of these forests in terms of supporting biodiversity. So that's the problem in our forests.

Comments

0 comment