views

Brainstorming Your Narrative

Decide what kind of story you want to tell. Though every story is different, most plays fall into categories that help the audience understand how to interpret the relationships and events they see. Think about the characters you want to write, then consider how you want their stories to unfold. Do they: Have to solve a mystery? Sometimes you can even have other people write the script for you . Go through a series of difficult events in order to achieve personal growth? Come of age by transitioning from childlike innocence to worldly experience? Go on a journey, like Odysseus’s perilous journey in The Odyssey? Bring order to chaos? Overcome a series of obstacles to achieve a goal?

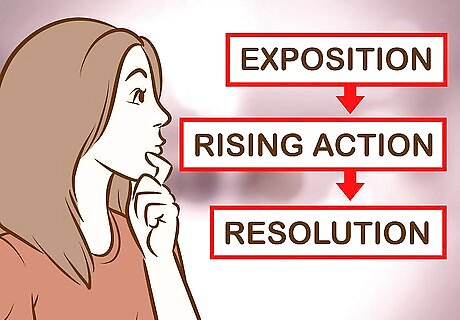

Brainstorm the basic parts of your narrative arc. The narrative arc is the progression of the play through beginning, middle, and end. The technical terms for these three parts are exposition, rising action, and resolution, and they always come in that order. Regardless of how long your play is or how many acts you have, a good play will develop all three pieces of this puzzle. Taken notes on how you want to flesh each one out before sitting down to write your play.

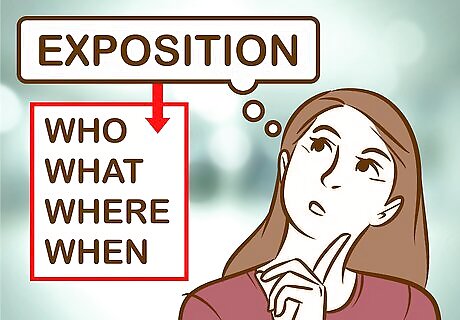

Decide what needs to be included in the exposition. Exposition opens a play by providing basic information needed to follow the story: When and where does this story take place? Who is the main character? Who are the secondary characters, including the antagonist (person who presents the main character with his or her central conflict), if you have one? What is the central conflict these characters will face? What is the mood of this play (comedy, romantic drama, tragedy)?

Transition the exposition into rising action. In the rising action, events unfold in a way that makes circumstances more difficult for the characters. The central conflict comes into focus as events raise the audience’s tension higher and higher. This conflict may be with another character (antagonist), with an external condition (war, poverty, separation from a loved one), or with oneself (having to overcome one’s own insecurities, for example). The rising action culminates in the story’s climax: the moment of highest tension, when the conflict comes to a head.

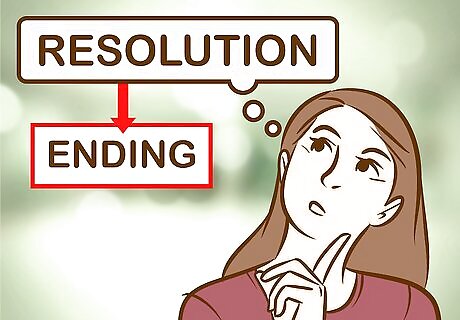

Decide how your conflict will resolve itself. The resolution releases the tension from the climactic conflict to end the narrative arc. You might have a happy ending, where the main character gets what he/she wants; a tragic ending where the audience learns something from the main character’s failure; or a denouement, in which all questions are answered.

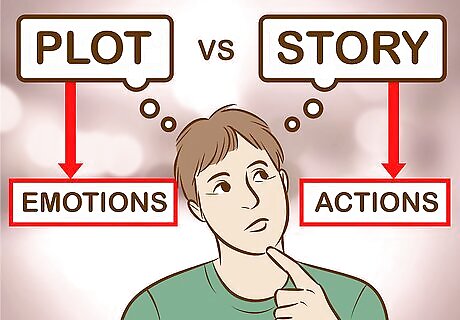

Understand the difference between plot and story. The narrative of your play is made up of the plot and the story — two discrete elements that must be developed together to create a play that holds your audience’s attention. E.M. Forster defined story as what happens in the play — the chronological unfolding of events. The plot, on the other hand, can be thought of as the logic that links the events that unfold through the plot and make them emotionally powerful. An example of the difference is: Story: The protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him. Then the protagonist lost his job. Plot: The protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him. Heartbroken, he had an emotional breakdown at work that resulted in his firing. You must develop a story that’s compelling and moves the action of the play along quickly enough to keep the audience’s attention. At the same time, you must show how the actions are all causally linked through your plot development. This is how you make the audience care about the events that are transpiring on stage.

Develop your story. You can’t deepen the emotional resonance of the plot until you have a good story in place. Brainstorm the basic elements of story before fleshing them out with your actual writing by answering the following questions: Where does your story take place? Who is your protagonist (main character), and who are the important secondary characters? What is the central conflict these characters will have to deal with? What is the “inciting incident” that sets off the main action of the play and leads up to that central conflict? What happens to your characters as they deal with this conflict? How is the conflict resolved at the end of the story? How does this impact the characters?

Deepen your story with plot development. Remember that the plot develops the relationship between all the elements of story that were listed in the previous step. As you think about plot, you should try to answer the following questions: What are the relationships between the characters? How do the characters interact with the central conflict? Which ones are most impacted by it, and how does it affect them? How can you structure the story (events) to bring the necessary characters into contact with the central conflict? What is the logical, casual progression that leads each event to the next one, building in a continuous flow toward the story’s climactic moment and resolution?

Deciding on Your Play’s Structure

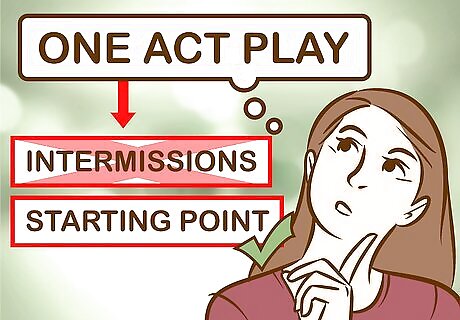

Begin with a one-act play if you are new to playwriting. Before writing the play, you should have a sense of how you want to structure it. The one-act play runs straight through without any intermissions, and is a good starting point for people new to playwriting. Examples of one-act plays include "The Bond," by Robert Frost and Amy Lowell, and "Gettysburg," by Percy MacKaye.Although the one-act play has the simplest structure, remember that all stories need a narrative arc with exposition, rising tension, and resolution. Because one-act plays lack intermissions, they call for simpler sets and costume changes. Keep your technical needs simple.

Don’t limit the length of your one-act play. The one-act structure has nothing to do with the duration of the performance. These plays can vary widely in length, with some productions as short as 10 minutes and others over an hour long. Flash dramas are very short one-act plays that can run from a few seconds up to about 10 minutes long. They’re great for school and community theater performances, as well as competitions specifically for flash theater. See Anna Stillaman's "A Time of Green" for an example of a flash drama.

Allow for more complex sets with a two-act play. The two-act play is the most common structure in contemporary theater. Though there’s no rule for how long each act should last, in general, acts run about half an hour in length, giving the audience a break with an intermission between them. The intermission gives the audience time to use the restroom or just relax, think about what’s happened, and discuss the conflict presented in the first act. However, it also lets your crew make heavy changes to set, costume, and makeup. Intermissions usually last about 15 minutes, so keep your crew’s duties reasonable for that amount of time. For examples of two-act plays, see Peter Weiss' "Hölderlin" or Harold Pinter's "The Homecoming."

Adjust the plot to fit the two-act structure. The two-act structure changes more than just the amount of time your crew has to make technical adjustments. Because the audience has a break in the middle of the play, you can't treat the story as one flowing narrative. You must structure your story around the intermission to leave the audience tense and wondering at the end of the first act. When they come back from intermission, they should immediately be drawn back into the rising tension of the story. The “inciting incident” should occur about half-way through the first act, after the background exposition. Follow the inciting incident with multiple scenes that raise the audience’s tension — whether dramatic, tragic, or comedic. These scenes should build toward a point of conflict that will end the first act. End the first act just after the highest point of tension in the story to that point. The audience will be left wanting more at intermission, and they’ll come back eager for the second act. Begin the second act at a lower point of tension than where you left off with the first act. You want to ease the audience back into the story and its conflict. Present multiple second-act scenes that raise the stakes in the conflict toward the story’s climax, or the highest point of tension and conflict, just before the end of the play. Relax the audience into the ending with falling action and resolution. Though not all plays need a happy ending, the audience should feel as though the tension you’ve built throughout the play has been released.

Pace longer, more complex plots with a three-act structure. If you’re new to playwriting, you may want to start with a one- or two-act play because a full-length, three-act play might keep your audience in its seats for two hours! It takes a lot of experience and skill to put together a production that can captivate an audience for that long, so you might want to set your sights lower at first. However, if the story you want to tell is complex enough, a three-act play might be your best bet. Just like the 2-act play, it allows for major changes to set, costumes, etc. during the intermissions between acts. Each act of the play should achieve its own storytelling goal: Act 1 is the exposition: take your time introducing the characters and background information. Make the audience care about the main character (protagonist) and his or her situation to ensure a strong emotional reaction when things start going wrong. The first act should also introduce the problem that will develop throughout the rest of the play. Act 2 is the complication: the stakes become higher for the protagonist as the problem becomes harder to navigate. One good way to raise the stakes in the second act is to reveal an important piece of background information close to the act’s climax. This revelation should instill doubt in the protagonist’s mind before he or she finds the strength to push through the conflict toward resolution. Act 2 should end despondently, with the protagonist’s plans in shambles. Act 3 is the resolution: the protagonist overcomes the obstacles of the second act and finds a way to reach the play’s conclusion. Note that not all plays have happy endings; the hero may die as part of the resolution, but the audience should learn something from it. Examples of three-act plays include Honore de Balzac's "Mercadet" and John Galsworthy's "Pigeon: A Fantasy in Three Acts."

Writing Your Play

Outline your acts and scenes. In the first two sections of this article, you brainstormed your basic ideas about narrative arc, story and plot development, and play structure. Now, before sitting down to write the play, you should place all these ideas into a neat outline. For each act, lay out what happens in each scene. When are important characters introduced? How many different scenes do you have, and what specifically happens in each scene? Make sure each scene’s events build toward the next scene to achieve plot development. When might you need set changes? Costume changes? Take these kinds of technical elements into consideration when outlining how your story will unfold.

Flesh out your outline by writing your play. Once you have your outline, you can write your actual play. Just get your basic dialogue on the page at first, without worrying about how natural the dialogue sounds or how the actors will move about the stage and give their performances. In the first draft, you simply want to “get black on white,” as Guy de Maupassant said.

Work on creating natural dialogue. You want to give your actors a solid script, so they can deliver the lines in a way that seems human, real, and emotionally powerful. Record yourself reading the lines from your first draft aloud, then listen to the recording. Make note of points where you sound robotic or overly grand. Remember that even in literary plays, your characters still have to sound like normal people. They shouldn’t sound like they’re delivery fancy speeches when they’re complaining about their jobs over a dinner table.

Allow conversations to take tangents. When you’re talking with your friends, you rarely stick to a single subject with focused concentration. While in a play, the conversation must steer the characters toward the next conflict, you should allow small diversions to make it feel realistic. For example, in a discussion of why the protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him, there might be a sequence of two or three lines where the speakers argue about how long they’d been dating in the first place.

Include interruptions in your dialogue. Even when we’re not being rude, people interrupt each other in conversation all the time — even if just to voice support with an “I get it, man” or a “No, you’re completely right.” People also interrupt themselves by changing track within their own sentences: “I just — I mean, I really don’t mind driving over there on a Saturday, it’s just that — listen, I’ve just been working really hard lately.” Don’t be afraid to use sentence fragments, either. Although we’re trained never to use fragments in writing, we use them all the time when we’re speaking: “I hate dogs. All of them.”

Add stage directions. Stage directions let the actors understand your vision of what’s unfolding onstage. Use italics or brackets to set your stage directions apart from the spoken dialogue. While the actors will use their own creative license to bring your words to life, some specific directions you give might include: Conversation cues: [long, awkward silence] Physical actions: [Silas stands up and paces nervously]; [Margaret chews her nails] Emotional states: [Anxiously], [Enthusiastically], [Picks up the dirty shirt as though disgusted by it]

Rewrite your draft as many times as needed. You’re not going to nail your play on the first draft. Even experienced writers need to write several drafts of a play before they’re satisfied with the final product. Don’t rush yourself! With each pass, add more detail that will help bring your production to life. Even as you’re adding detail, remember that the delete key can be your best friend. As Donald Murray says, you must “cut what is bad, to reveal what is good.” Remove all dialogue and events that don’t add to the emotional resonance of the play. The novelist Leonard Elmore’s advice applies to plays as well: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

Comments

0 comment