views

X

Research source

The thing is, defensiveness isn't always healthy behavior for our relationships at home or work: the shields go up, the brain shuts down, and not much gets in or out. To be less defensive, you'll need to learn how to control your emotions, take criticism, and also be more empathetic to others.

- An easy way to curb your defensiveness is to force yourself to take a long, deep breath before you respond to someone; by pausing to breathe, you’ll be more likely to catch defensive impulses before you act out.

- Active listening is a skill, and it can take time to train yourself how to track other people when they speak, but it’s essential if you want to avoid unnecessarily defensive reactions.

- Make sure that you fully understand what the other person says before you reply to them, and ask a bunch of follow-up questions to get clarity if you need it.

- The best antidote for defensiveness is responsibility, so try going out of your way to acknowledge when you’re wrong, always apologize, and accept any consequences as they occur.

Controlling Your Emotions

Recognize the physical signs of defensiveness. A defensive reaction puts you in a fight-or-flight mode: this means that your body will show physical signs and put you in a state of heightened tension. Try to learn to recognize these signs. That way, you'll be able to nip any defensiveness in the bud when it starts. Ask yourself: is your heart speeding up? Do you feel tense, anxious, or angry? Is your mind racing to come up with counter-arguments? Have you stopped listening to others? Look at your body language – what is it like? People who are feeling defensive often reflect that in their body language, crossing the arms, turning away, and closing off their body to others. Do you feel a strong urge to interrupt? Rest assured that one of the biggest giveaways that you're being defensive is saying, “I am NOT being defensive!”

Take deep breaths. Your body is less able to take in information when it's in a heightened state of tension. To counteract the body's fight-or-flight reaction, try to bring your nervous system down by slow, measure breathing. Calm yourself before you do or say anything. Inhale slowly to the count of five and exhale again to the count of five. Make sure to take a long, deep breath after your peers have stopped talking and you start. Give yourself space to breathe when you talk, as well. Slow down if you are talking too fast and racing through points.

Don't interrupt. Interrupting to dispute someone's point or criticism is another big sign that you're being defensive. This is not helpful and makes you seem insecure and pigheaded. What's more, it's an indication that you still haven't gotten your emotions under control. Try counting to ten every time you have the urge to butt in. After ten seconds, there's a good chance the conversation will have moved on and your rebuttal won't be relevant. Increase the count to twenty or even thirty if you are still tempted. Catch yourself when you interrupt, as well. Stop speaking mid-sentence and apologize for your rudeness, in order to build up your discipline.

Ask to have the conversation later. If your emotions are too heightened to have a reasonable exchange, consider excusing yourself and asking to pick up the conversation later. You won't get much from a talk with co-workers or family members if you can't listen to what they have to say. This doesn't mean avoiding the conversation – it means postponing it. Say something like, “I'm really sorry Cindy. We need to have this talk, but right now is not a good time for me. Can we do this later in the afternoon?” Make sure to affirm the importance of the conversation while excusing yourself, i.e. “I know this is an important topic to you and I want to talk about it calmly. But right now I don't feel so calm. Can we try later?

Find ways to beat stress. When you're defensive, your body is under elevated levels of stress. To help yourself calm down, find ways to relax and release that tension. This will not only help you manage the extra stress but can also help you improve your wellbeing. Relaxation techniques can help you slow your breathing as well as focus your attention. Try yoga, meditation, or tai chi, for example. You can also try more active ways to relax. Working out through walking, running, sports, or other forms of exercise can have similar stress-reducing effects.

Learning to Take Criticism

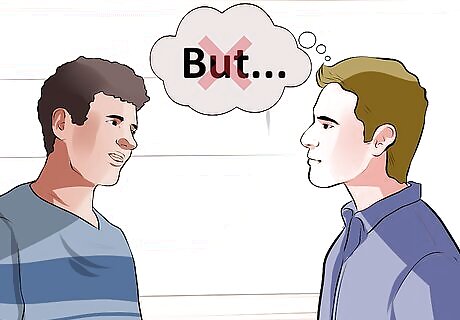

Banish the word “but...” When you're defensive, you want to start a lot of sentences with “but” to prove others wrong. This isn't just a word, it's a mental barrier. It conveys that you really don't care or want to care about the opinions of others – and taking and accepting constructive criticism is precisely about caring. Hold your tongue if you have the urge to say “but,” at least until you have heard the other person out. Instead of “but,” consider asking questions that force you to think about and express what others are saying to you, i.e. “Just so I understand, you think that my report's analysis is incorrect?” or “Do I have this right, you want me to run the numbers again?”

Ask for specifics. Rather than getting mad, ask questions. Ask others to be more specific about their opinions and their criticisms. This will help you to digest what they're saying and also show that you aren't dismissing their perspectives. You might say something along the lines of, “Edwin, can you give me an example of a time you thought I was condescending?” or “What is it specifically that makes you feel I'm not affectionate enough?” Ask to understand the criticism. Don't nitpick. Asking a question just so you can poke holes in the answer is another form of defensiveness. Getting specifics will also help you to decide whether to accept the feedback or not. Constructive criticism (e.g. “Your work has analytical weaknesses” or “You don't express your emotions well”) will have valid reasons behind it, while destructive criticism (e.g. “Your work is trash” or “You're an awful person”) will not.

Don't counter-criticize. Learning to take criticism takes reflection and openness. It can also take self-control. Avoid the urge to lob your own criticisms, as this will only make it seem like you are lashing out. Instead, withhold your objections for a later time when you can have a legitimate conversation about them. Fight the urge to attack the person who's criticizing you or their opinions, i.e. “Now you're just being a jerk, Mom” or “Look who's talking about being sarcastic!” Also resist the urge to point out flaws about someone else's work or behavior, i.e. “Well I don't know what you're complaining about. Bill does the same thing!” or “What was wrong with my report? Alex's report was awful!”

Try not to take things personally. Giving and receiving feedback is an important skill in the workplace and in families and, ideally, it should create dialogue with a goal of improvement. Try to give others the benefit of the doubt and don't interpret criticism as a personal attack. Their feedback is probably meant to serve a bigger aim or done with love. If you feel under attack, ask yourself why. Do you feel offended? Insecure? Do you fear the loss of face, your personal reputation, or your position? Consider who is giving you the criticism. A family member or friend is less likely to attack you personally. In fact, they are probably trying to help you out of love and concern. Lastly, consider what others are trying to achieve with their feedback – is it to improve a product, good, or service at work? Do they want to improve relationships or communication at home? In these cases, the feedback isn't just about you as a person.

Developing Empathy for Others

Listen to what others are saying. Having empathy means being able to put yourself in another person's shoes and to understand her state of mind and how she feels. To do this, though, you have to be able to listen. Follow the advice above, but also use active listening techniques. Focus your attention on what the other person is saying. There is no need to say anything at first. In fact, it's better to just let her talk. Don't interrupt to give your opinion. At the same time, though, signal that you're paying attention by nodding, acknowledging points, or with verbal cues like, “Yes” or “I see.” Do these things without breaking into the flow of conversation.

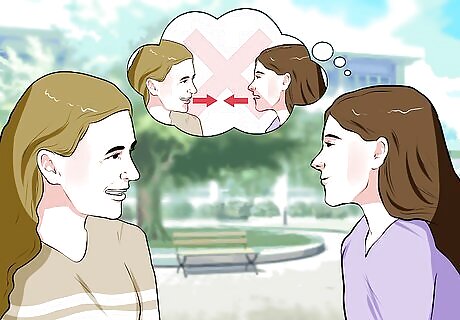

Try to suspend your judgement. To empathize, you'll need to temporarily push your own opinions and judgments to the side until you hear your peer out. This can be hard. However, the point is to try to understand what the other person is feeling and not to insert your own perspective. This means you should focus on her experience. You don't ultimately need to accept the other person's perspective. But you have to let go of your own opinions, value scale, and perspective to gain access to her mental state. Do not dismiss the other person's perspective, for one thing. Insisting that the topic isn't important or telling your peer to “Just get over it” is completely dismissive and defensive. Avoid comparisons, too. Your experiences may be totally different and miss or minimize what your peer is feeling. For instance, it's best not to say something like “You know, I used to feel the same way when X happened…” Don't try to offer solutions, either. The point of empathy isn't necessarily to solve a problem, but to hear a person out.

Repeat what others say back to them. If you want to really listen to another person and what they have to say, engage them actively but respectfully. Restate points to make sure that you've understood – without interrupting. You can also consider asking questions. When your peer has expressed a point, repeat the main point back to her in slightly different words, i.e. “If I understand you, you're upset because you don't feel we communicate well.” This not only shows that you're paying attention, but helps you to grasp the other person's feelings, whatever they may be. Ask open-ended questions to draw out further details, too. “You're pretty frustrated with me, no?” doesn't add much. However, you can elicit more helpful conversation with a question like, “What is it about our relationship that frustrates you so much?”

Let others know that you've heard them. Last, affirm what your peer has said. Let her know that you've listened, understood, and appreciated the importance of the conversation, even if you haven't yet resolved the problem. This communicates that you are being open-minded rather than defensive and leaves room for future dialogue. Say something like, “What you've told me isn't easy to hear, Jack, but I know it's important to you and I will consider it” or “Thank you for telling me this, Aisha. I'll think what you've said over carefully.” You still don't have to agree or accept your peer's position. However, by being empathetic rather than defensive you can open the way for compromise and a solution.

Comments

0 comment