views

Voicing Your Concern

Sit your loved one down. DPD is a serious mental health disorder and affects the sufferer, but also family members, friends, and caregivers. It can cause a good deal of emotional and psychological stress on all parties involved. If you think that a loved one might have DPD, consider sharing your concerns in an honest but loving manner. Pick a time to talk when you and your loved one are calm. Try sometime in the evening, after dinner, or when you are home together. Make it a private conversation so that you can express yourself openly. For example, you might talk at home, either the two of you or with other loved ones present.

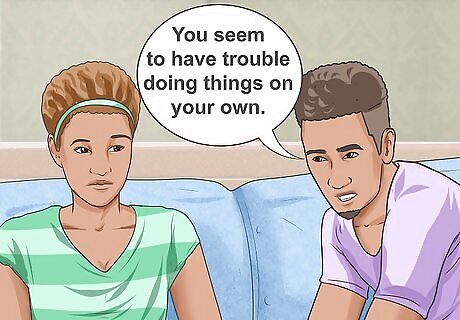

Present your concern as an opinion. When you talk, present your concerns about your loved one’s patterns of behavior. DPD is characterized by “clinginess” and an inability to make decisions without help – an over-reliance on others. It is serious and can lead to long-term impairment in social life, relationships, and work. Try to be honest but non-confrontational and loving. Express your concerns as an opinion. People with DPD may not seem “sick” in an obvious way or recognize that there is a problem. Instead of saying, “This behavior isn’t normal for an adult ,” say something like “You seem to have trouble doing things on your own.” Since people with DPD often have low feelings of self-worth, use “I” statements to be as non-judgmental as you can. Instead of saying, “You never take any responsibility for yourself” say something like “I notice that you get really anxious when you have to make decisions for yourself. Why is that?” Suggest that your loved one talk to a doctor or see a therapist, i.e. “I wonder if you have a dependency issue? Maybe it would be best to talk to someone about it.”

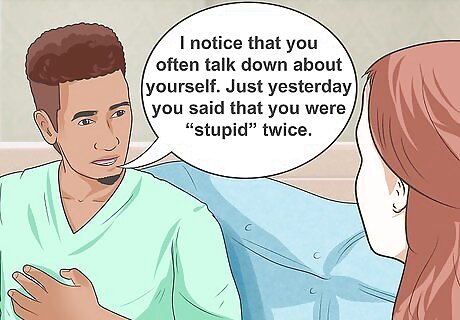

Use concrete examples to highlight the problem. The best way to demonstrate to someone with DPD that there is a problem is to use very concrete examples. Think of cases in the past when your loved one’s dependence concerned you. Say that, as you see it, these examples point to a problem that needs treatment. For example, “I notice that you often talk down about yourself. Just yesterday you said that you were “stupid” twice.” Or, “I worry because it’s so hard for you to be by yourself. Do you remember last year when I wanted to go on vacation for a week and you got so upset at the thought of being alone? I had to cancel everything.”

Follow up with your loved one. One of the difficulties with DPD is that sufferers go to great lengths to get approval and support from others. They can be submissive and passive even if they disagree, because they fear losing a close relationship. Follow up after the talk. Your loved one may well have agreed outwardly with everything you said, but did not believe it or act on your advice. You cannot force someone to seek treatment. However, repeat your concern if the loved one hasn’t acted and the situation has continued. For example, you might say, “Have you thought about what I said a few weeks ago? Are you willing to talk to a doctor about it?”

Helping On a Daily Basis

Do some research on your own. If you think that a loved one might have DPD, one of the most important things you can do to help is to educate yourself. Learn about the illness. Learn about its symptoms and how it affects sufferers. Try to understand what your loved one is experiencing and feeling. The internet is a great initial resource. You can start by searching Google for “Dependent Personality Disorder” and by reading up on the disorder at reputable websites like the Cleveland Clinic, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and the Merck Manual. Look for books on the disorder, as well. Try your local bookstore or library and ask for volumes on DPD. Some titles include The Dependent Personality, The Dependent Patient, and Healthy Dependency: Leaning on Others While Helping Yourself.

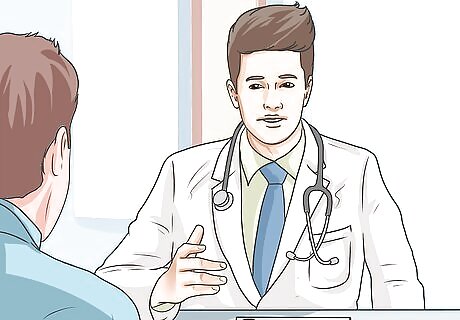

Consult with mental health professionals. You can also think about seeking expert advice on your loved one’s problem. Talk to mental health professionals who know about DPD, like doctors, psychologists, psychiatrists. These people may not be able or willing to talk in specifics about your loved one, but they can answer your general questions and advise you on informational literature and what you can do to help. Talking with a doctor can alert you to more of the traits of DPD and how they can affect you, like emotional blackmail, projection, and mirroring, testing relationships, and sometimes even stealing. We don’t know what exactly causes DPD. However, you can also learn more from a mental health professional about the possible biological, cultural, and psychological factors.

Look into treatment options. Seriously consider looking into how DPD is treated, as well. The most common treatments for DPD are kinds of therapy, especially Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. There are other kinds, too, though, like group therapy and psychodynamic therapy. Try to find out as much as you can about these different approaches and what they can offer. Know that while some people with DPD take medications, these are normally for other issues that arise alongside DPD like anxiety or depression. Use should be carefully monitored, too, so that individuals don’t develop dependency on the drugs.

Be willing to pitch in, to a limited extent. Be ready and willing to help to support your loved one’s treatment. You might pitch in by taking your loved one to an appointment or by lending a hand around the house with chores, especially if your loved one is depressed. However, be aware that you should not help too much. You might offer to help with errands, chores, groceries, or other normal activities if your loved one is going through a down period. However, always keep in mind that helping someone with DPD too much can be damaging. Since they seek out dependence, you could end up enabling the disorder and making it worse. Do offer encouragement and kind words, however. Your loved one will need them.

Avoiding Over-Attachment

Recognize the risk of over-attachment. As said, people with DPD tend to be very passive and compliant in order to gain approval from others. They develop unhealthy dependencies on other people and can even resort to emotional blackmail to protect the relationship. If you have a loved one with DPD, you will have to be very careful about enabling the disorder. Be wary of taking on responsibility for your loved one’s decisions, treatment, and affairs. Also be aware of how much time and attention you are devoting to your loved one. People with DPD are often very needy and seek out constant attention and validation. Encourage autonomy. People with DPD do not trust their own ability to make decisions. Part of improvement is for them to learn personal autonomy and to take responsibility for themselves. Find ways to encourage this.

Set limits on your responsibilities. To avoid over dependence, make every effort to limit your role in your loved one’s treatment and life as a whole. This may feel painful to you and your loved one. However, it is necessary in establishing limits and in teaching your loved one autonomy. Be willing to help your loved one, but set clear limits. For example, “OK Adam, I will help you research therapists but you have to call to set up the appointment” or “I’m willing to drive you to your first appointment, Gina. After that, you need to drive yourself.” People with DPD can benefit from assertiveness training, so that they learn ways to stand up for themselves. However, you too might benefit from training in assertiveness to extricate yourself from a too-dependent relationship.

Pitch in with problems that have clear beginnings and ends. If and when you do decide to help your loved one, make sure that the tasks are manageable and not open-ended. Be sure that the problems have clear beginnings or ends. Otherwise, you may find yourself sucked into more and more responsibility and again enabling your loved one. For example, say your loved one wants help with balancing a check book. Rather than an open-ended agreement, specify that you’ll show your loved one how to balance the check book once and only once. Try not to get drawn in to emotional issues unrelated to the check book. Try the same technique with other problems. Set definite limits on how you will contribute to solving a problem and stick to them.

Comments

0 comment