views

- Break and indent paragraphs involving 2 or more speakers.

- Use quotation marks around all words spoken by a character.

- Break a long speech into multiple paragraphs.

Getting the Punctuation Right

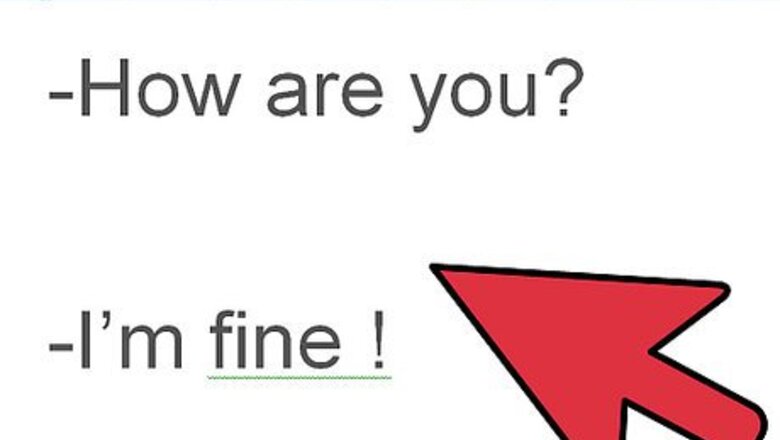

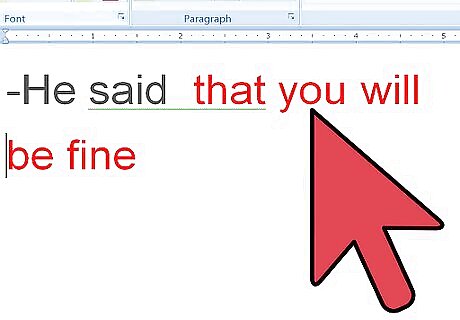

Break and indent paragraphs for different speakers. Because dialogue involves two or more speakers, readers need something that lets them know where one character’s speech ends and another’s begins. Indenting a new paragraph every time a new character begins speaking provides a visual cue to help readers follow the dialogue. Even if a speaker only utters half a syllable before they’re interrupted by someone else, that half-syllable still gets its own indented paragraph. In English, dialogue is read from the left side of the page to the right, so the first thing readers notice when looking at a block of text is the white space on the left margin.

Use quotation marks correctly. American writers generally use a set of double quotation marks (“ “) around all of the words that are spoken by a character, as seen in this example: Beth was walking down the street when she saw her friend Shao. "Hey there!" she said as she waved. A single set of quotation marks can include multiple sentences, as long as they are spoken in the same portion of dialogue. For example: Evgeny argued, "But Laura didn’t have to finish her dinner! You always give her special treatment!" When a character quotes someone else, use double-quotes around what your character says, then single-quotes around the speech they’re quoting. For example: Evgeny argued, “But you never yell ‘Finish your dinner’ at Laura!” The reversal of roles for the single and double-quotation mark is common outside of American writing. Many European and Asian languages use angle brackets (<< >>) to mark dialogue instead.

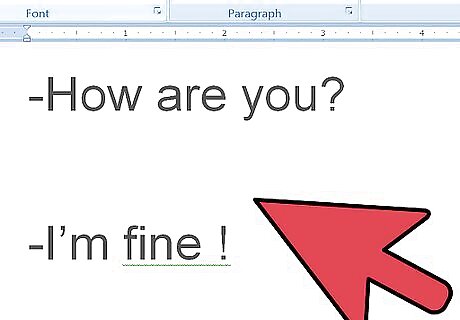

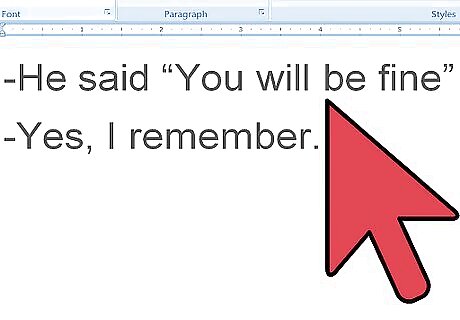

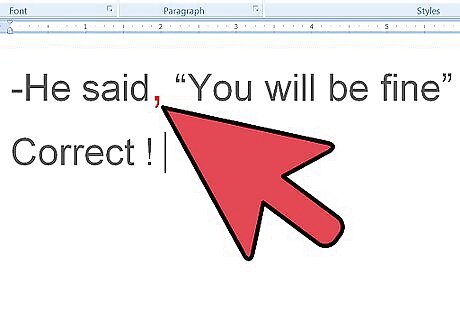

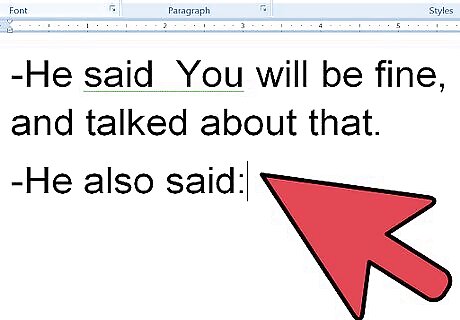

Punctuate your dialogue tags properly. The dialogue tag (also called the signal phrase) is the part of the narration that makes clear which character is speaking. For example, in the following sentence, Evgeny argued is the dialogue tag: Evgeny argued, “But Laura didn’t have to finish her dinner!” Use a comma to separate the dialogue tag from the dialogue. If the dialogue tag precedes the dialogue, the comma appears before the opening quotation mark: Evgeny argued, “But Laura didn’t have to finish her dinner!” If the dialogue tag comes after the dialogue, the comma appears before (inside) the closing quotation mark: “But Laura didn’t have to finish her dinner,” argued Evgeny. If the dialogue tag interrupts the flow of a sentence of dialogue, use a pair of commas that follows the previous two rules: “But Laura,” Evgeny argued, “never has to finish her dinner!”

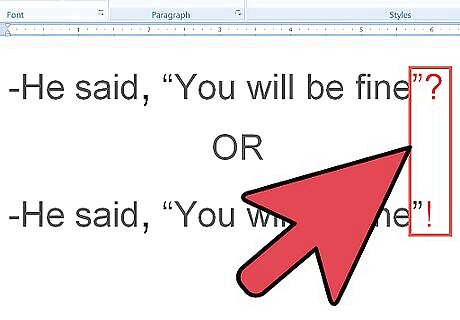

Punctuate questions and exclamations properly. Place question marks and exclamation points inside the quotation marks, like so: "What is going on?" Tareva asked. "I am so confused right now!" If the question or exclamation ends the dialogue, do not use commas to separate the dialogue from dialogue tags. For example: "Why did you order mac-and-cheese pizza for dinner?" Fatima asked in disbelief.

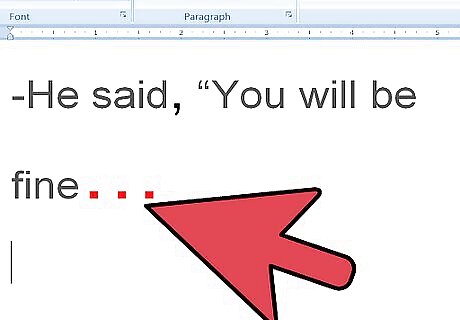

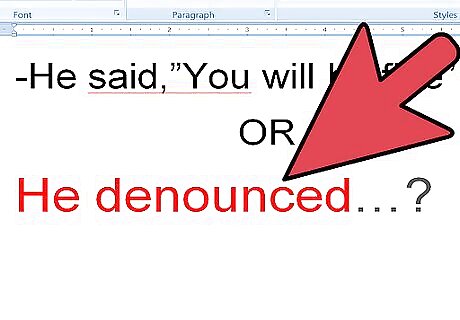

Use dashes and ellipses correctly. Dashes (--, also known as em-dashes) are used to indicate abrupt endings and interruptions in dialogue. They are not the same as hyphens, which should generally only be used to create compound words. Ellipses (...) are used when dialogue trails off but is not abruptly interrupted. For example, use a dash to indicate an abruptly ended speech: "What are y--" Joe began. You can also use dashes to indicate when one person's dialogue is interrupted by another's: "I just wanted to tell you--""Don't say it!""--that I prefer Rocky Road ice cream." Use ellipses when a character has lost her train of thought or can't figure out what to say: "Well, I guess I mean..."

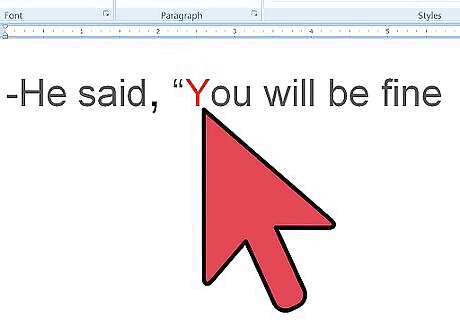

Capitalize the quoted speech. If dialogue begins grammatically at character's sentence (as opposed to beginning mid-sentence), capitalize the first word as though it's the first word of the sentence, even though you may have narration before it. For example: Evgeny argued, "But Laura didn’t have to finish her dinner!" The “b” of “But” does not technically begin the sentence, but it begins a sentence in the world of the dialogue, so it is capitalized. However, if the first quoted word isn’t the first word of a sentence, don’t capitalize it: Evgeny argued that Laura “never has to finish her dinner!”

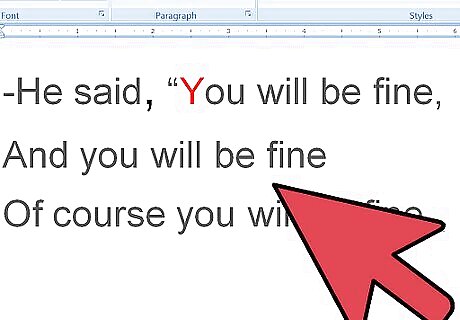

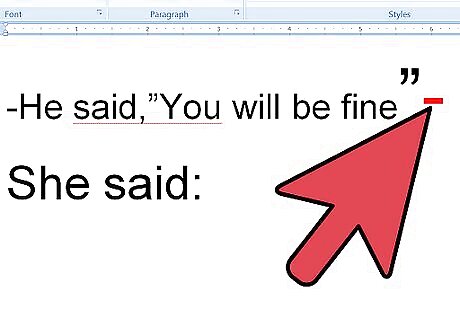

Break a long speech into multiple paragraphs. If one of your characters delivers an especially long speech, then, just like you would in an essay or in the non-dialogue parts of your story, you should break that speech up into multiple paragraphs. Use an opening quotation mark where you normally would, but don’t place one at the end of the first paragraph of the character’s speech. The speech isn’t over yet, so you don’t punctuate it like it is! Do, however, place another opening quotation mark at the beginning of the next paragraph of speech. This indicates that this is a continuation of the speech from the previous paragraph. Place your closing quotation mark wherever the character’s speech ends, as you normally would.

Avoid using quotation marks with indirect dialogue. Direct dialogue is someone actually speaking, and quotation marks are used to indicate it. Indirect dialogue is reported speech, not the act of someone speaking directly, and quotation marks are not used. For example: Beth saw her friend Shao on the street and stopped to say hello.

Making Your Dialogue Flow Naturally

Make sure the reader knows who is speaking. There are a couple of ways to do this, but the most obvious way is to use dialogue tags accurately. The reader can’t get confused if your sentence clearly indicates that Evgeny is speaking, not Laura. When you have a long dialogue that’s clearly being held between only two people, you can choose to leave out the dialogue tags entirely. In this case, you would rely on your paragraph breaks and indentations to let the reader know which character is speaking. You should leave out the dialogue tags when more than two characters are speaking only if you intend for the reader to be potentially confused about who is speaking. For example, if four characters are arguing with one another, you may want the reader to get the sense that they’re just hearing snatches of argument without being able to tell who’s speaking. The confusion of leaving out dialogue tags could help accomplish this.

Avoid using over-fancy dialogue tags. Your instinct might be to spice up your story using as many variations of "she said" and "he said" as possible, but tags such as "she groused" or "he denounced" actually distract from what your characters are saying. "He said" and "she said" are so common that they tend to become essentially invisible to readers.

Vary the placement of your dialogue tags. Instead of starting every dialogue sentence with “Evgeny said,” “Laura said,” or “Sujata said,” try placing some dialogue tags at the end of sentences. Place dialogue tags in the middle of a sentence, interrupting the sentence, to change the pacing of your sentence. Because you have to use two commas to set the dialogue tag apart (see Step 3 in the previous section), your sentence will have two pauses in the middle of the spoken sentence: “And how exactly,” Laura muttered under her breath, “do you plan on accomplishing that?”

Substitute pronouns for proper nouns. Whereas proper nouns name specific places, things, and people and are always capitalized, pronouns are uncapitalized words that stand in for full nouns, including proper nouns. To avoid the repetition of your characters’ names, substitute the appropriate pronouns from time to time. Some examples of pronouns include I, me, he, she, herself, you, it, that, they, each, few, many, who, whoever, whose, someone, everybody, and so on. Pronouns must always agree with the number and gender of the nouns they’re referring to. For example, the only appropriate pronouns to replace “Laura” are singular, feminine ones: she, her, hers, herself. The only appropriate pronouns to replace “Laura and Evgeny” are plural, gender neutral ones (because English loses gender when pluralized): they, their, theirs, themselves, them.

Use dialogue beats to mix up your formatting. Dialogue beats are brief moments of action that interrupt a sequence of dialogue. They can be good ways to show what a character is doing at the same time as telling what they're saying, and can provide a nice action boost to a scene. For example: "Hand me that screwdriver," Sujata grinned and wiped her grease-covered hands on her jeans, "I bet I can fix this thing."

Use believable language. The biggest problem with dialogue is often that it doesn’t sound believable. You talk perfectly normally every day of your life, so trust your own voice! Imagine how your character is feeling and what they want to say. Say it out loud in your own words. That’s your starting point. Don’t try to use big fancy words that nobody uses in normal conversation; use a voice you’d hear in everyday life. Read the dialogue back to yourself and see if it feels normal.

Avoid info-dumping in dialogue. Using dialogue to provide exposition not only creates dull dialogue, it also often results in speeches that are so long that they're likely to lose the reader's attention. If you need to communicate details about plot or backstory, try to show them through narration, not dialogue.

Comments

0 comment