views

X

Research source

If you think you're ready to become a falconer, take a moment to learn the demanding requirements you'll need to meet and start taking your first steps toward becoming a full-fledged falconer!

Making Sure You Are Ready

Before you start, contact your state/local wildlife agency. As with hunting, the laws surrounding the sport of falconry can vary greatly from one jurisdiction to the next. Before you consider becoming a falconer, get in touch with your local wildlife agency to ensure that falconry is legal in your area and that you'll be able to meet the requirements for practicing the sport. A complete list of wildlife agencies for the U.S. and Canada is available at the website for the North American Falconers Association (NAFA). Note: the rest of the instructions in this guide are intended only as general guidelines. Always defer to the advice of qualified wildlife experts.

Make sure you can meet the time commitment to become a falconer. The decision to become a falconer is one that will affect the way you spend your time for many years. Some things to keep in mind while making your decision include: The training process to become a falconer is a very long one. As noted above, an apprenticeship alone generally lasts at least two years, while seven years or more may be required to reach master status. A raptor requires near-constant care with no days off or holidays. This usually amounts to about half an hour each day, every day, though on hunting days this can easily be four to five hours. If you can't care for your raptor personally (such as, for instance, if you go on a vacation), it will be your responsibility to arrange for its care in your absence. A healthy raptor can live into its twenties, though many falconers eventually return raptors that they catch into the wild.

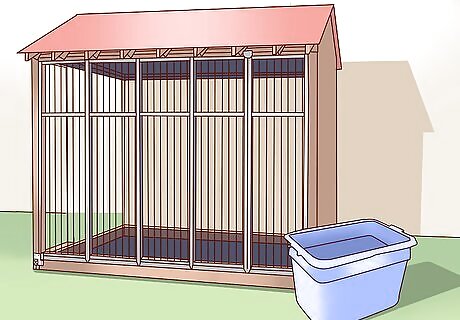

Make sure you have the temperament for falconry. Simply put, falconry isn't for everyone. While it can be an immensely rewarding, enriching experience, being a falconer involves doing things that some people may find objectionable or unpalatable. These include: Killing animals. Most falconers use their raptors for hunting animals in some way. This aspect of the sport that requires an honest self-assessment: Are you comfortable killing wild animals? Are you emotionally prepared to see a predator capture and kill prey? Are you willing to put wounded animals out of their misery? If you're not sure, strongly consider first trying out more traditional forms of hunting, which are often have lower barriers to entry for beginners. Confining your raptor to a mews. Raptors are usually housed in an enclosure called a mews. Raptors are almost always happy and comfortable in a well-maintained mews, but some people dislike seeing animals housed in captivity. Note that most environmental surveys agree that falconry has limited impact on wild raptor populations. Cleaning and caring for your raptor. Raptors are reasonably clean animals, but being a falconer still requires getting messy sometimes. For instance, you'll need to occasionally clean your raptor's mews, which can accumulate waste, bones, and so on over time.

Make sure you have the resources to become a falconer. It is hard to pinpoint an exact cost for becoming a falconer — experiences can vary greatly. However, it's safe to say that falconry is not a low-cost sport by any means. You should expect to spend at least several thousand dollars on your raptor over the course of its life. To be a falconer, you must be prepared to take financial responsibility for your raptor. Things that you will need to be prepared to pay for include: Food for your raptor Veterinary costs Travel to meetings, hunting locations, and visits with other falconers Licensing/permit fees Shelter and equipment for your raptor — depending on local laws, this may also include an inspection fee Books and reference materials

Make sure you have access to proper land. To be a falconer, you must have hunting land on which to exercise your bird and practice your sport. This can't be just any land — in fact, nearly all urban and suburban land will be unsuitable for falconry. This land must have the appropriate type and quantity of game available for hunting. Falcons require large open expanses of land on which to hunt high overhead while hawks and small accipiters can hunt in smaller fields and farms. Land with roads, power lines, urban life, barbed wire fences or where gun hunting is permitted may be unsuitable because of potential threats to the health of the raptor or falconer. Even if you do not personally have the land required, some farmers will permit you to use their land at no cost. Note that it is customary to offer farmers something small in return, like throwing them a yearly party to show your appreciation. If you have friends who own large tracts of rural land, note that you may still need written permission in order to use their land.

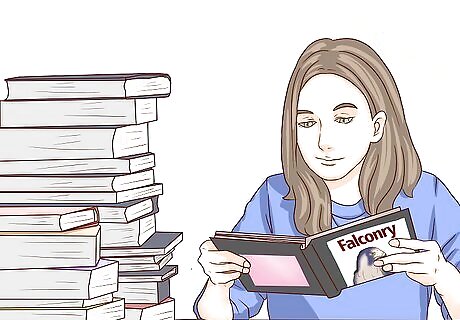

Study falconry. Still not sure whether you want to become a falconer? One of the best ways to determine if you have the motivation and drive to become a falconer is to learn as much as you can about the sport. Having the passion to learn about falconry from books, videos, experts, and other resources can indicate that you have the passion and dedication necessary for becoming a falconer. A list of reading material recommended by the NAFA is available here. A Bond With the Wild, a collection of essays assembled by NAFA, is a great resource for beginners to start to get a sense of what falconry is "all about." You may also want to try talking to falconers via online forums and discussion boards.

Becoming an Apprentice

Talk to your local authorities to determine which permits you'll need. Becoming a falconer isn't as simple as going out into the wild and catching a bird. Raptors are protected by state/provincial, federal/national and international law and you will need the appropriate permits and licenses before getting a hawk or practicing falconry. Contact your local wildlife agency as early as possible so that you will have plenty of time to complete all of the necessary requirements to legally practice falconry. These permits can take quite a long time to be approved, so it is important to plan ahead. In fact, most falconry resources agree that it is best to apply for these permits a year in advance of the hunting season in which you wish to begin falconry. Note that, in addition to a falconry permit, you may also need an ordinary hunting license, which can require you to take hunter education courses. At this point, you will probably also want to schedule the test you'll need to take to obtain your permit. See below for more information. Once again, here is a list of relevant wildlife agencies in the U.S. and Canada courtesy of NAFA.

Contact your local falconry organization. While you're waiting for your government paperwork to be processed, get in touch with the nearest falconry organization to start the process of becoming an apprentice. Not all states, provinces, or regions will have these sorts of clubs or organizations, but many do. Here is a list of falconry club affiliates courtesy of NAFA. Consider attending meetings at falconry clubs even if you aren't fully certified to practice the sport yet. This is a great way of meeting people, learning about the sport, and creating relationships which can later transition into sponsorships.

Find a sponsor. Falconers progress through three levels of proficiency as they train: Apprentice, General Falconer, and Master Falconer. As an apprentice you are required to have a sponsor for at least two years. Sponsors can be either General or Master falconers. Different falconry clubs and individuals may have different requirements of their potential apprentices — some sponsors might even require an aspiring falconer to train with them for a year before they will consider sponsorship. You sponsor is one of the most important connections you will have as a falconer-in-training. This person will help you learn, guide you, and give you advice over several years. Choose someone that you enjoy spending time with and that whose expertise you respect. It is much, much easier to get an experienced falconer to agree to become your sponsor if you have a personal connection with this person and this person believes you to have a competent understanding of the sport. You'll probably want to start attending falconry meetings and browsing the reading material described above so that, over time, you'll pick up the concepts and terminology of falconry.

Take the falconry test for your permit. In almost all jurisdictions, a written examination administered by your local wildlife agency must be passed before you obtain your license or permit. This examination will test your knowledge of birds of prey, raptor biology, bird health care, laws pertaining to falconry, and so on. Generally, you will want to schedule your test well in advance (even as early as the very first time you contact your state/provincial wildlife department.) These agencies will usually require a fee for the examination and may only offer the test at certain times throughout the year, depending on your particular state/province. Note that some states/provinces require you to have found a sponsor before taking this examination, while others do not have this as a prerequisite. Ask your local wildlife agency to find out specific requirements.

Getting a Bird

First, construct a mews for your bird. As noted above, raptors used for falconry are housed in structures called mews. Before you try to get a bird, make sure you have proper facilities to house it. Under the guidance of your sponsor (and while keeping local laws and regulations in mind), construct facilities to house your bird. These facilities will usually have to be inspected by your local wildlife agency before you can legally keep a raptor in them. In general, facilities can be made out of wood or fiberglass and cannot have chicken wire on the roofs. Natural flooring, pea gravel, concrete or wood shavings can be used for the floor. There must be perches with at least one by a window. One bird will require a space of at least 6 feet (1.8 m) by 8 feet (2.4 m) by 7 feet (2.1 m) high; this will have to be doubled with a wall in between for two birds. Many jurisdictions require an attached weathering yard where birds can be tethered with a leash. These facility requirements can differ by region so, as always, contact your state/provincial wildlife agency for specific details. You will also need a bath container and a reliable scale to monitor the health of your bird.

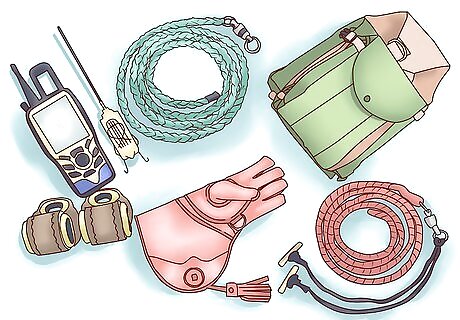

Make or buy your equipment. Falconry requires specialized equipment to manage your bird. Required equipment can vary by bird species, individual and local laws and regulations, so check with your local falconry club to make your checklist. Making this equipment is often cheaper than buying it, and, if you're seriously dedicated to falconry, this can be a valuable skill to have. However, your equipment will almost always need to be inspected for quality at the same time as your facilities are inspected, so only attempt to make your equipment if you are an experienced craftsmen. In most cases, you will need an anklet (leash to attach to the bird’s leg), an identification band, a button (braided end of a leash, also called a knurl), a creance (long line for training the bird), a gauntlet (left hand gloves worn by falconer), a hood, jesses (leather strips to which the lease will be attached), the leash, a lure (for training) and telemetry (for locating the bird when it goes out of sight).

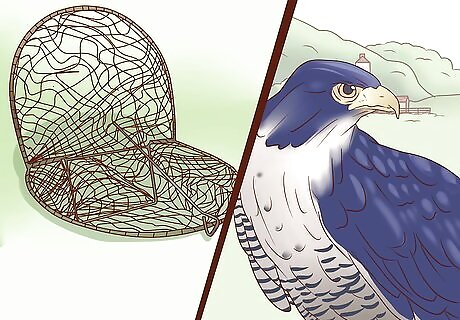

Trap your bird. Many sponsors will require apprentices to trap their first bird themselves. In the United States, apprentices are only allowed to catch an immature passage Red-tailed hawk or an American kestrel of any age (except in Alaska, where they may also catch Goshawks.) Although most jurisdictions will allow you to catch your bird at any time of the year, most falconry resources will recommend catching it in the fall and early winter, as this will generally give young birds enough time to become competent hunters while still remaining mentally malleable enough to tame. Note that falconry birds cannot be purchased for apprentices in the U.S. Trapping a raptor is a topic that is too complex to explore in detail in this article. For a great first-time guide, try the trapping article at The Modern Apprentice website. Make sure to get the go-ahead from your sponsor before attempting to trap your first bird. You'll also want to make sure that all of your applications and application fees been processed and that you've received all proper documentation before attempting to acquire your first bird.

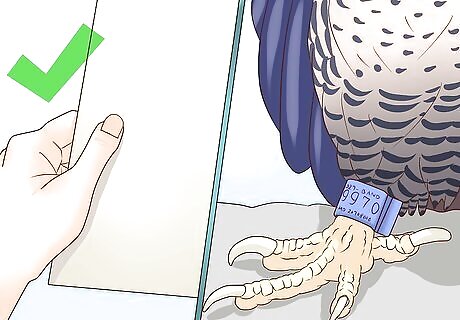

Submit your paperwork and tag your bird. After catching your bird, most wildlife jurisdictions will require you to tag it in case it flies away and is found by someone else. Depending on your location, there may be additional paperwork you need to fill out in order to register your bird — as always, consult with your local wildlife agency for more information. In the United States, you have 10 days to submit this paperwork after catching your bird.

Taking Your Next Steps

Start training your bird. Now that you have captured your first bird, you are officially a falconer. Follow your sponsor's instructions carefully and be patient — it will usually take about six weeks to train your bird for hunting. See the linked article for more information. In addition, the 1997 issue of Hawk Chalk (the official newsletter magazine of NAFA) has a great article on using a technique called Operant Conditioning to train raptors. You can find it here.

Progress to General Falconer (and eventually Master Falconer). As you move through the ranks of falconry, you'll enjoy greater freedom and privileges than you did as an apprentice. See below for a brief run-down of each classification as specified for Washington State (most jurisdictions will be similar): Apprentice Falconer Only allowed to have one bird at a time May take only an American Kestrel or Red-tailed hawk from the wild (Goshawks allowed in Alaska). Expected to train extensively with sponsor. General Falconer May have up to three wild-caught birds at once. Additional variety of birds available for capture (see state bill WAC 232-30-152 for more information.) May sponsor an apprentice after two years at the General level. Master Falconer Must demonstrate "at least five years experience as a General Falconer and show expertise in successful hunting and care of their birds, and experience with more than one species of raptor." May have up to five wild-caught birds at once. May have an unlimited number of captive-bred birds for falconry purposes.

Join NAFA. Most falconers join NAFA, the North American Falconers Association, as apprentices. Membership in NAFA carries many perks, including access to falconry-related news, training resources, discussion groups, and much more. NAFA requires all applicants to fill out a simple application form. Membership dues must be paid when submitting your application and once per year after that — North American Membership dues are $45.00 per year, while Foreign Membership dues are $65.00 per year. In addition, you will also want to plan on joining your state or province's falconry association (where applicable.) For example, falconers in Washington State should join the Washington Falconers Association.

Comments

0 comment