views

Before the coronavirus outbreak, Dr. Lindy Fox, a dermatologist in San Francisco, used to see four or five patients a year with chilblains — painful red or purple lesions that typically emerge on fingers or toes in the winter.

Over the past few weeks, she has seen dozens.

“All of a sudden, we are inundated with toes,” said Fox, who practices at the University of California, San Francisco. “I’ve got clinics filled with people coming in with new toe lesions. And it’s not people who had chilblains before — they’ve never had anything like this.”

It’s also not the time of year for chilblains, which are caused by inflammation in small blood vessels in reaction to cold or damp conditions. “Usually, we see it in the dead of winter,” Fox said.

Fox is not the only one deluged with cases. In Boston, Dr. Esther Freeman, director of global health dermatology at the Massachusetts General Hospital, said her telemedicine clinic is also “completely full of toes. I had to add extra clinical sessions, just to take care of toe consults. People are very concerned.”

The lesions are emerging as yet another telltale symptom of infection with the new coronavirus. The most prominent signs are a dry cough and shortness of breath, but the virus has been linked to a string of unusual and diverse effects, like mental confusion and a diminished sense of smell.

Federal health officials do not include toe lesions in the list of coronavirus symptoms, but some dermatologists are pushing for a change, saying so-called COVID toe should be sufficient grounds for testing. (COVID-19 is the name of the illness caused by the coronavirus.)

Several medical papers from Spain, Belgium and Italy described a surge in complaints about painful lesions on patients’ toes, Achilles' heels and soles of the feet; whether the patients were infected was not always clear, because they were otherwise healthy and testing was limited.

Most cases have been reported in children, teens and young adults, and some experts say they may reflect a healthy immune response to the virus.

“The most important message to the public is not to panic — most of the patients we are seeing with these lesions are doing extremely well,” Freeman said.

“They’re having what we call a benign clinical course. They’re staying home, they’re getting better, the toe lesions are going away.”

Scientists are just beginning to study the phenomenon, but so far chilblain-like lesions appear to signal, curiously enough, a mild or even asymptomatic infection. They may also develop several weeks after the acute phase of an infection is over.

Patients who develop swollen toes and red and purple lesions should consult their primary care doctor or a dermatologist to rule out other possible causes. But, experts said, they should not run to the emergency room, where they risk being exposed to the coronavirus or exposing others if they are infected.

“The good news is that the chilblain-like lesions usually mean you’re going to be fine,” Fox said. “Usually it’s a good sign your body has seen COVID and is making a good immune reaction to it.”

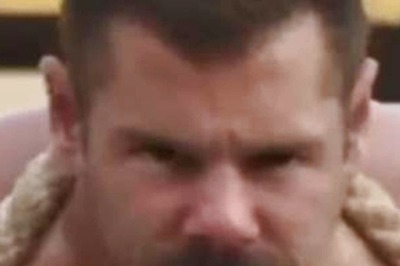

Patients who get the painful lesions are often alarmed. They appear most frequently on the toes, often affecting several toes on one or both feet, and the sores can be extremely painful, causing a burning or itching sensation.

At first, the toes look swollen and take on a reddish tint; sometimes a part of the toe is swollen, and individual lesions or bumps can be seen. Over time, the lesions become purple in color.

Hannah Spitzer, 20, a sophomore at Lafayette College who is finishing the academic year remotely at her home in Westchester County, New York, has lesions on all 10 of her toes, so uncomfortable — painful during the day, and itchy at night — that she can’t put anything on her feet, not even socks.

Walking is difficult, and she has trouble sleeping. “At first I thought it was my shoes, but it got worse and worse,” Spitzer said. “Most of my toes are red, swollen, almost shiny. It looks like frostbite.”

She has used hydrocortisone and Benadryl to alleviate the discomfort, and said ice is also helpful. Doctors say the lesions disappear on their own within a few weeks.

Adding to the mystery is that some teens and young adults with the lesions have tested negative for the coronavirus.

Spitzer had a test shortly after developing the lesions, and the result was negative, but she is convinced the toe lesions are a delayed response to an earlier infection that was so mild she barely noticed it.

“I’ve never had anything like this,” she said. “It’s completely new.”

A recent paper by doctors in Spain, published in the International Journal of Dermatology, described six cases of patients with toe lesions and included pictures of the chilblain-like bumps that patients had emailed to their physicians.

Most of the patients were teens or young adults, including one 15-year-old who found out he had COVID-19 pneumonia when he went to the emergency room seeking medical attention for his toes.

Another patient was a 91-year-old man who had been hospitalized with the coronavirus three weeks earlier, and had recovered and returned home.

While dermatologists say it’s not unusual for rashes to appear along with viral infections — like measles or chickenpox — the toe lesions surprised them.

Other problems like hives have also been linked to the coronavirus, but COVID toes have been the most common and striking skin manifestation.

Patients with viral infections often get a pink bumpy rash called morbilliform, or hives, Fox said, but added that the toe lesions were “unexpected.”

The toe cases make up half of all reports filed by skin doctors around the world to a new international registry started by the American Academy of Dermatology, which is tracking the complications.

No one knows exactly why the new coronavirus might cause chilblain-like lesions. One hypothesis is that they are caused by inflammation, a prominent feature of COVID-19. Inflammation also causes one of the most serious syndromes associated with the coronavirus, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Other hypotheses are that the lesions are caused by inflammation in the walls of blood vessels, or by small micro clots in the blood. (Clotting has been another feature of the disease.)

The lesions seen in otherwise healthy people appear to be distinct from those that doctors are seeing in some critically ill COVID-19 patients in intensive care, who are prone to developing blood clots.

Some of these clots may be very small and can block the tiny vessels in the extremities, causing rashes on the toes, said Dr. Humberto Choi, a pulmonologist and critical care physician at the Cleveland Clinic.

Some experts now believe COVID toe should be recognized as sufficient grounds for testing, even in the absence of other symptoms.

“This should be a criteria for testing, just like loss of smell, and shortness of breath and chest pain,” Fox said.

Roni Caryn Rabin c.2020 The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment