views

The world has used up two-thirds of its carbon space for a 2-degrees-Celsius temperature rise, consumed 35% of known fossil-fuel reserves and cut a third of global forests.

These are the numbers climate negotiators from 190 countries must struggle with between November 30 and December 11, 2015, in Paris, if the world is to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, a level that, scientists say, is a red line.

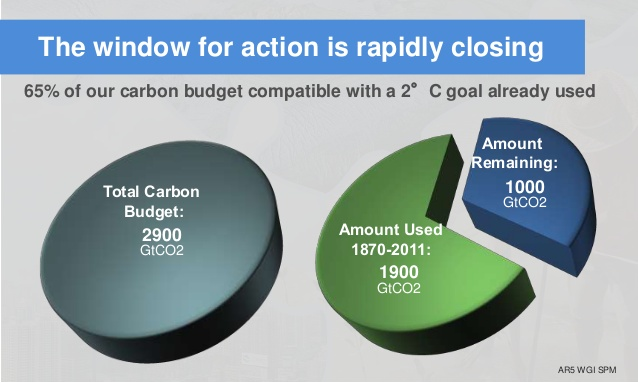

The world has 1,000 giga tonnes of carbon-dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e)–called carbon space or developmental space–to put out in the atmosphere to limit temperature rise to 2 degrees celsius from pre-industrial levels, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) fifth assessment report (AR5).

A temperature rise beyond that, experts warn, will be catastrophic. That doesn’t leave much wriggle room for India.

“India should be aligning with the other third world countries–they are our natural allies–and push the U.S, E.U, and China to increase their commitments, while also offering to conditionally increase its commitments,” said Nagraj Adve, a member of India Climate Justice.

While global leaders meet in Paris to discuss climate change, “the (Conference of Parties) COP 21 is about how much carbon space is left and who gets how much of that space,” said Sagar Dhara, an environmental engineer and energy expert based in Hyderabad.

This is what the great, global wrangling over targets, means and ends is about.

Source: IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report

Rising temperatures are hurting people

The world has already put out 2,000 GtCO2e into the atmosphere since the industrial revolution began in the mid-18th century, using 35% of the known 1,700 GtCO2e of conventional fossil fuel reserves and cutting a third of the 60 million sq km of global forests, Dhara noted in “Keep the Climate, Change the Economy.”

The result: A temperature increase of 0.85 degrees Celsius since the industrial revolution, which has already proved dangerous to people and environment in terms of wilder weather, species migration and extinction, food and water security and conflicts.

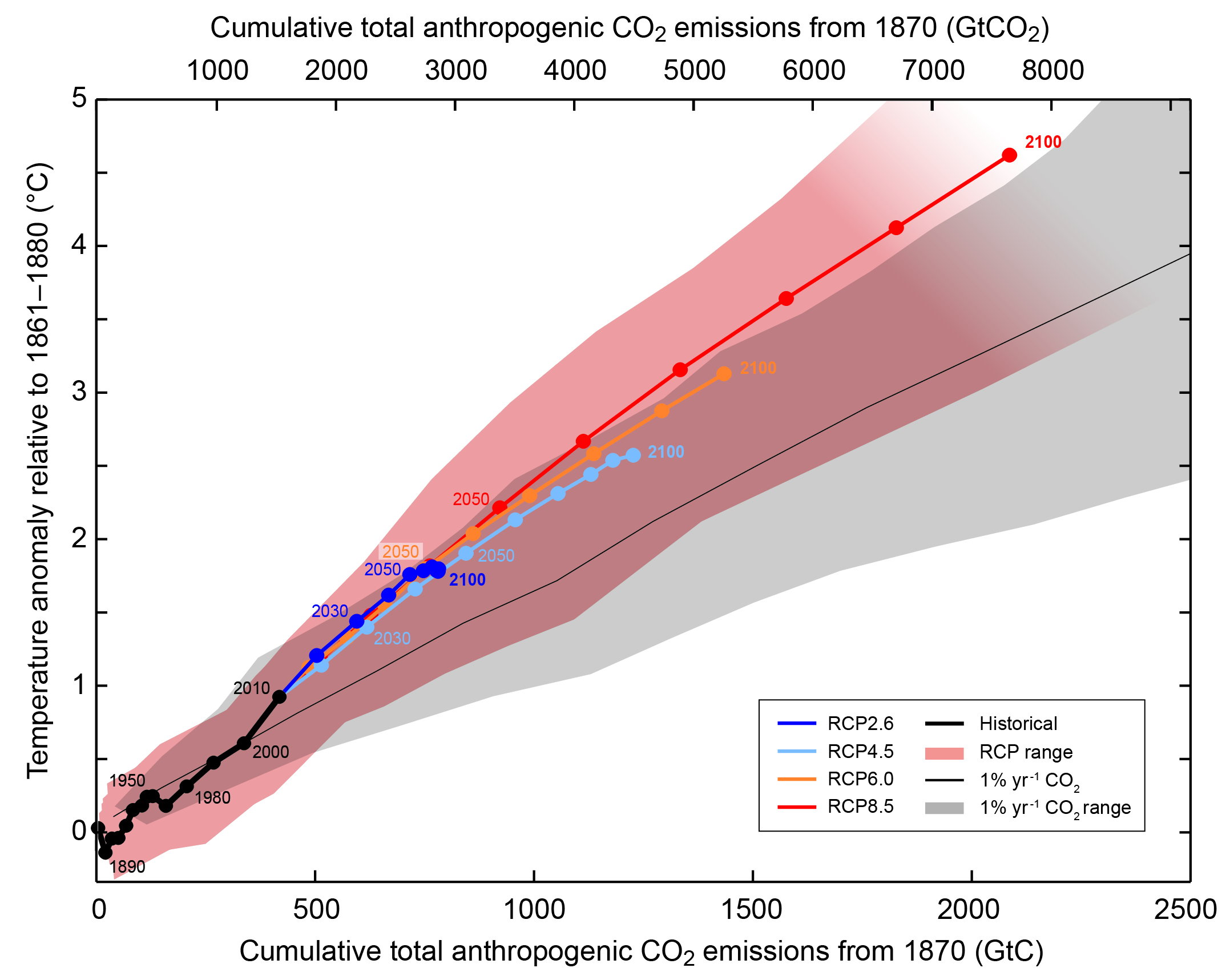

Source: IPCC Working Group I

The stakes have never been as high, as the Paris talks begin and current obligations wear off in 2020. The task ahead is clear: hammer out an agreement on future emissions to stave off the tipping point.

The sticking points are over who will get what share of the carbon space and who will bear the financial cost.

At the end of COP 20 held in December 2014, the countries submitted their plans of climate action–known as Intended Nationally-Determined Contributions (INDCs)–including emission targets as per the Lima Call for Climate Action.

The road to Paris: Why the pledges may be too little, too late

Since climate co-operation began at the international level in 1997, progress made has been incompatible with the scale of the problem, leaving poor countries at the receiving end of the climate crisis.

The Kyoto Protocol, signed in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan, called on countries to rein in greenhouse gases (GHGs) and obliged 43 developed countries–called Annex 1 (A1) Parties, including what was the then-Soviet Union–to cut GHGs by 5 %–32 GtCO2e–between 2008 and 2012, compared to their 1990 levels, excluding transport emissions.

Developing countries were exempt from the obligations. During the 1990-2012 Kyoto Protocol period, developed countries reduced their emissions by 16% or 32 GtCO2e.

The twist in the tale, Dhara told IndiaSpend, is that emission reduction is fictitious. First, the emissions are accounted for in the country that produces goods and services. Over the past two decades, the developed countries countries have turned into net importers of goods and services from the developing countries, particularly India and China.

That means, emissions were accounted for by the developing countries and not developed countries. “This helped them maintain their high consumption levels at low costs,” Dhara said.

Apart from that, shrinking economic activity in Canada, Japan, Australia, Western and Eastern Europe also contributed to emission reduction.

Net trade emissions of developed countries were 40% more than the stated goal in Kyoto Protocol, according to Dhara’s calculations.

‘India set to experience worst ever environmental degradation’

Now that the countries have pledged their emission shares, “it’s all about filling up the carbon space and who gets what share,” Dhara said.

The leftover carbon space will be filled up by 2040 with pledges; without pledges, by 2035, according to Dhara’s calculations.

At the current negotiations, as in the past, the developing countries will pitch their own slice of developmental space while developed countries will claim, what he termed, “squatter rights”.

In the case of India and other developing countries, even the demand for equity is a weak argument, he said.

For one, developed countries emitted around 65% of historic emissions, cumulative emissions since 1750, and their historic emissions, per person, is 1,200 tonne, 40 times more than every Indian, according to Dhara.

Even if you give the entire carbon space to third world countries, they are not going achieve living standards of the developed world, Dhara said.

All one has to do is to look at China and see how destructive rapid economic growth has been, said Vaclav Smil, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Manitoba, Canada.

“Assuming that India’s goal is to replicate China’s recent development means that the country is poised to experience the worst-ever environmental degradation in history affecting every aspect of the biosphere from unprecedented levels of air pollution to water pollution, biodiversity loss and run-away urbanisation,” Smil told IndiaSpend in an e-mail interview.

All this puts third world countries like India in a serious bind, Dhara said.

“If they decline to play ball with developed countries at COP 21 regarding their own emission cuts, they will be toast to the effects of climate change as they’re economically and geographically the most vulnerable,” he said.

“If they play ball with developed countries and accept emission cuts, their own development, as is popularly understood and touted, will suffer, and inequality and disparity between developed and developing countries will increase. Whichever way you slice this, you’re in a deep ditch.”

What’s more, even the emission pledges are not enough–although many say something is better than nothing .

A report from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change on the aggregate effect of the INDCs shows that the temperature rise will be 2.7 degrees Celsius by the end of this century and not 2 degrees, a rise beyond which, scientific consensus says, could be catastrophic.

The Emissions Gap Report 2010 from the United Nations Environment Programme tackles the question–Are the Copenhagen Accord Pledges Sufficient to Limit Global Warming to 2 degrees or 1.5 degrees Celsius?

A key finding is that under business-as-usual projections, global emissions could reach 56 GtCO2e (range of 54-60 GtCO2e) in 2020, leaving a gap of 12 GtCO2e.

To remain in line with a rise of 2 degrees celsius, Dhara said, the emissions should have peaked by 2020 and then dropped off, which appears to be a remote possibility with current trends.

Comments

0 comment