views

Oberammergau, Germany: There is no doubt in the mind of the Rev. Thomas Gröner that what happened in his village was a miracle.

He says he has proof, too. The pandemic had ravaged the village, with 1 in 4 people believed to have died. “Whole families, gone,” Gröner said.

Then villagers stood before a cross and pledged to God that if he spared those who remained, they would perform the Passion play — enacting Jesus’ life, death and resurrection — every 10th year forever after.

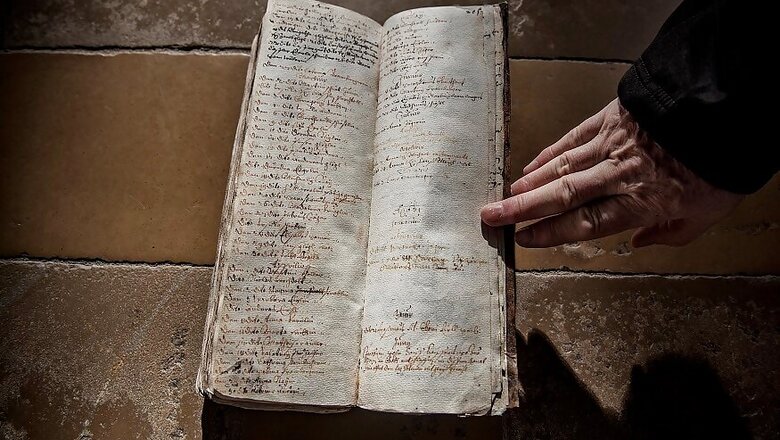

It was 1633. The bubonic plague was still raging in Bavaria. But legend has it that after the pledge, no one else in the village died from it. Standing in his church underneath the cross where villagers had once made their promise, Gröner held out a battered leather-bound book.

“Look,” he said, his fingers scanning a faded page with tightly packed handwriting that abruptly stops three-quarters down. “They recorded dozens and dozens of deaths and then — none.”

For nearly four centuries, the people of Oberammergau (pronounced oh-ber-AH-mer-gow) more or less kept their promise, celebrating their salvation from one pandemic — until another pandemic forced them to break it.

This year’s Passion play, scheduled to premiere in May and run through the summer, had to be abandoned because of the coronavirus. An epic production, cast with local residents as actors, the play would have brought half a million visitors to the village and 2,500 people, or half of Oberammergau, onto the world’s biggest open air stage.

The production would have been the 42nd since the play’s premiere in 1634. Canceled only twice — in 1770 during the Enlightenment and in 1940 during World War II — the play has been performed once every decade and sometimes twice, for special anniversaries. It had to be postponed once before — after too many men had died in World War I to field a cast.

Now, as Easter weekend approaches, Oberammergau is praying for another miracle.

So far, the village does not have a single known case of COVID-19. “Maybe the pledge still protects the village?” Susanne Eski, a dressmaker, said hopefully as she prepared to put costumes for the Passion play into storage one recent afternoon.

But outside Oberammergau the number of cases has been rising, and most fear that it is just a matter of time. On Palm Sunday, there were more than 91,000 infections in Germany and more than 1,300 deaths.

For centuries, kings and queens, leaders and celebrities have flocked to this village in the Bavarian Alps to be immersed in the story of salvation.

Since the mid-1960s, the play has been criticized for its crude anti-Semitism, first by Jewish groups and later by the Roman Catholic Church itself. Adolf Hitler reportedly loved it and deemed it “important to the Reich.”

Christian Stückl has directed the Passion play for three decades, gradually ridding it of its most egregious anti-Semitic symbolism and opening the cast to Protestants, Muslims and married women. He welled up with emotion when he announced that this year’s performances would be postponed by two years.

The village had been building up to this moment for a decade.

For months, hotels and restaurants had staffed up to cope with the onslaught of visitors. Local craftsmen worked overtime to sculpt the stage props. Volunteers helped sew costumes. Rehearsals brought together all age groups in the village, from toddlers to grandparents, sometimes daily.

And, in keeping with an ancient village statute, many men had stopped shaving a year ago to allow hair to sprout freely, A.D. 30 style.

But the rehearsals have stopped. The Passion play theater, with its 4,500 seats, stands empty. Props and costumes are going into storage.

Only the beards remain: Both village hairdressers are shut because of the coronavirus. “If you didn’t know this was Oberammergau, you’d think this village is full of hipsters or jihadis,” joked Cengiz Görür, 20, a son of a local restaurant owner and the first Muslim to get a leading part in the Passion play.

He was cast as Judas, the play’s traditional villain, which, as the newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung recently wrote, “some outside observers find very modern, others a little nasty.” The director said he got the role for his great acting talent.

It has been more than two weeks since the postponement was announced, and a collective sense of gloom has given way to an anxious calm. Like elsewhere in Germany, Oberammergau is adapting to the new reality of life in a pandemic — but perhaps more than elsewhere, villagers are looking at their fate through the prism of their local history.

The story of the plague profoundly shaped this village, remarked Eva Reiser, who was to play Mary. “How will the coronavirus change us and our world?” she wondered. “What will be the stories they tell about us?”

Already, the coronavirus has given new significance to the words Frederik Mayet, who was to play Jesus, had been rehearsing.

When Jesus addresses the people of Jerusalem, he talks about how “poverty and disease are carrying you off.” In two years, when the pandemic has taken its toll and the Passion play is resurrected, Mayet said, “that sentence will have a whole different meaning.”

Stückl, the director, can trace his own family back to the days of the plague. Its first victim was one of his ancestors, the caretaker of the church.

Wild-haired and chain-smoking, Stückl is a lifelong Catholic but is not so sure that what happened in 1633 was a miracle. The pledge was made in October, he pointed out, just as winter set in. The plague bacterium does not do well in the cold.

“There is probably a scientific explanation,” he said. In times like these, humans need stories of hope and redemption, he acknowledged, but they also need to trust in science.

These days, under government orders, the streets of Oberammergau have emptied and the two village schools closed. The bakery and butcher are still open, but handwritten signs urge customers to enter only two at a time. All religious services are canceled, too.

The economic fallout has been immediate and brutal, said Anton Preisinger, who was going to play Pilate, the Roman governor who orders Jesus’ crucifixion.

His hotel, owned by his family since the 19th century, went from being fully booked to “zero bookings.” He had to let 13 people go. “Social distancing hurts when social contact is your livelihood,” he said.

But during a pandemic, social distancing is vital. And Oberammergau knows this firsthand. “We’ve done it before,” Mayet said. In 1632 it looked as if the village might escape the plague. All surrounding villages had been devastated. In nearby Bad Kohlgrub only one married couple was said to have survived.

But Oberammergau had been spared. It had, in modern parlance, gone into quarantine — a sort of self-imposed isolation meant to keep villagers in and visitors out.

Guards patrolled village boundaries. They erected plague fires as a deterrence. “It was social distancing, 17th-century style,” Mayet said. “The village went into lockdown. It closed its borders.”

And for a while it worked.

But one night, a villager who was working in a neighboring village was so desperate to see his family that he slipped past the guards. Kaspar Schisler brought the plague with him.

Everybody in the village knows his name. There is even a street named after him. “No one wants to be Kaspar Schisler,” Reiser said. “No one wants to be the person who brings the virus into the village.”

Reiser, who works as a flight attendant when she is not playing the mother of God, has been aware of the coronavirus for longer than most in Oberammergau. In late January, a Chinese passenger on a flight from Munich to Lyon was suspected to have contracted the virus.

It turned out to be a false alarm. But after that, Reiser started counting the days through the 14-day incubation period every time she found herself in a crowded place, obsessively washing her hands and keeping her distance from her grandmother, 92.

“She wants to live through one more Passion play,” Reiser said.

In Oberammergau a lifetime is often measured in Passion plays. This would have been her grandmother’s 10th.

An hour’s drive from Oberammergau, deep in the woods, there is a chapel dedicated to a little-known saint who is only now being rediscovered — St. Corona, patron saint of resisting epidemics, Gröner said.

There are hard times ahead, he said. But everything has two sides. Perhaps something good will come of this crisis, he said: the return of solidarity and compassion for one another and the planet.

“In a way,” Gröner said, “the story of suffering and salvation they have been rehearsing onstage is now playing out in real life.”

Comments

0 comment