views

Whatever Kamal Haasan does, he does with panache. It was no different when Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal flew down to Chennai on September 21 to meet and discuss politics with the cine star and now wannabe politician.

In recent months, Haasan has been very vocal about the raging political turmoil in Tamil Nadu triggered by the death of then chief minister J Jayalalithaa.

On August 15, he asked why nobody had demanded that Chief Minister E Palaniswami resign over alleged corruption.

He also met Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, a CPM leader, recently, but clarified that he has no plans to join hands with the Left.

Against this backdrop, Haasan’s meeting with Kejriwal received much attention.

“There are rare people who have the courage to stick their neck out. Kamal Haasan ji happens to be one of them. He should enter politics. We had a very good meeting and exchanged a lot of ideas,” said Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal at a press interaction at Haasan’s Eldams Road office in Chennai.

Haasan, though, maintained a cryptic stance. “The reason why we (Kejriwal and Haasan) got together is the purpose — it is singular. I have always been that and he has a great national profile of fighting against corruption and communalism. So I also have a little reputation similar to that and it is no wonder that we decided to have a dialogue on the existing situation,” the actor said.

He called it a “learning curve” for himself, but stopped short of stating that he would indeed enter politics.

But what does it mean to be a politician in India in these times? And, in particular, in Tamil Nadu — a state that has grown up for six decades with a peculiar social justice movement which combined identity, self-respect and imbued a capitalistic character while preaching a quasi-Communist ideology to the masses?

A politician these days can’t help but be in touch with the people. He must attend birth ceremonies of the voters, turn up at deaths, give gifts of cash or kind at kaadhu-kutthu (ear piercing) functions, fund religious festivals at temples or mosques or churches.

It also means listening to endless lines of people who pour out their civic and other woes, getting admissions for the children of their voters in schools and colleges, providing money to wipe off debts of the poorest of the poor.

To be a politician is to walk through the dusty dirt roads of villages in the searing heat of the summer and address their drinking water issues. It is also about tying the veshti up to the waist and plunging headlong into flood waters to rescue those living in huts and in slums.

The issue Haasan is highlighting — corruption — was once not a game-changing issue at the polls. In the 1970s, when All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) founder MG Ramachandran (popularly known as MGR) accused arch rival and Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) chief K Karunanidhi of corruption, he did win the election, but not because the people voted ‘anti-corruption’.

Tamil Nadu voted for a mesmeric and beloved screen icon. The people had also voted against the police terror unleashed by Karunanidhi during his tenure against trade unions and other forms of dissent.

Since then, corruption has been a recurring theme in every election, be it with MGR, Karunanidhi, Jayalalithaa or Stalin, Karunanidhi’s heir apparent. The hustings, however, represented a cocktail of issues — freebies for some, anti-incumbency for others, cash for votes for some and in 2011, land grabbing by the ruling party made the electorate punish the DMK.

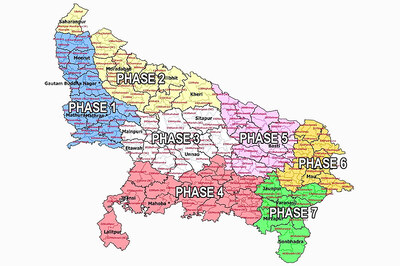

Apart from these, a complex balancing of caste votes and a keen awareness of the divisive and vicious caste fractures in rural Tamil Nadu have been honed to perfection by the two powerful political forces in the state — the AIADMK and DMK.

In every village of Tamil Nadu, there is at least one representative of the DMK and one of the AIADMK. The same cannot be said of the other parties in the state. It is the key reason why the mandate has been handed to one or the other party since 1967.

Can Kamal Haasan become the consummate politician in such a Daedalian political milieu? Tweeting and meeting the Chief Ministers of Kerala and Delhi might win him eyeballs on national television, but the votes can be won only if he gets down to the sweaty grimy toil of realpolitik.

Haasan no doubt is attempting to seize an opportunity thrown up by the bickering within the ruling AIADMK, which has exposed a gaping void in Tamil Nadu politics. He has shown he has the politician’s gumption, but does he have the politician’s tenacity?

Haasan is also not the first Tamil actor throwing his hat in the political ring. Moreover, what does he stand for apart from anti-corruption and communalism as he claims?

No one really knows.

And that’s not his only challenge.

Haasan is a “class hero” and not a “mass hero”, one who makes critically acclaimed movies rather than potboilers.

Not surprisingly, his fan club is much smaller than that of counterparts such as Rajinikanth, Vijay and Ajith. He would do well to begin actual work rather than drop tantalising hints about his almost improbable political entry.

(Sandhya Ravishankar is a senior journalist who covers Tamil Nadu politics. Views are personal)

Comments

0 comment