views

In the last week of July, Kerala started reporting 20,000+ daily new COVID-19 cases (approx. half of India’s daily new cases). The test positivity rate (TPR) continued to be more than 10 per cent (national average is 1.8 per cent) and the state also had two-fifth of the total active COVID-19 cases in the country. While the number of cases has come down in most Indian states, Kerala and Maharashtra have reported sustained transmission, thereby contributing a majority of new COVID cases in the country. In addition, a few other states in the South as well as in the Northeast including Assam have also reported a rise in cases. Understandably, the pandemic situation in Kerala has received a lot of attention and the situation demands a more calm assessment and nuanced analysis.

In an epidemic or pandemic, more so when caused by a novel pathogen, an effective response means slowing down the transmission (which allows time to prepare health systems) and then reducing the impact (through better care, as assessed by mortality rates). Finally, the aim of the pandemic response is to implement control measures to reverse and halt the transmission (through vaccination, restrictions and lockdowns).

Kerala’s Strategy, So Far

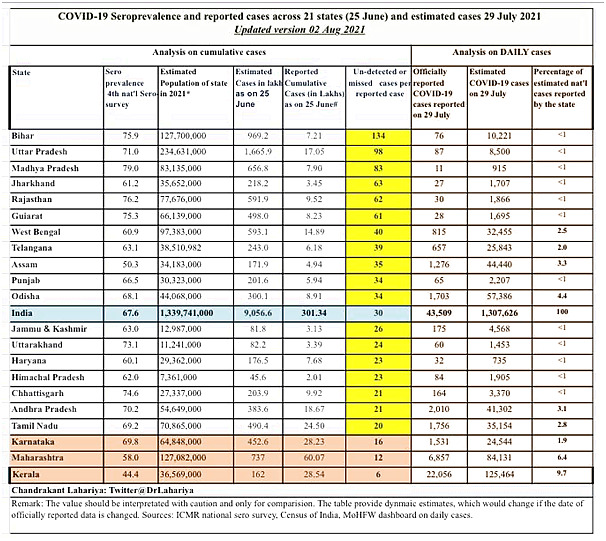

If we analyse the pandemic response of Kerala, we will find that the state has successfully delayed the transmission. Fifteen months into the COVID pandemic, the fourth national seroprevalence survey in India reported the lowest seroprevalence of 44.6 per cent in Kerala among 21 states (Table)[1]. Clearly, the measures to contain the transmission have been effective in the state. On the other parameter of reducing the impact, the case fatality rate in Kerala has remained around 0.5 per cent while the national average is around 1.3 per cent. In fact, at the peak of the second wave when there was a crisis of hospital beds, oxygen supply and critical medical supplies in many Indian states, the health system in Kerala was strained but never overwhelmed [2].

Finally, on measures to contain the transmission and halt the spread of COVID-19, Kerala is among the few Indian states that are still doing extensive contact tracing and targeted COVID-19 testing in high-risk populations and in high transmission settings. This is resulting in high TPR. The state arguably has the best case detection rate, with one in every six infections being picked up. The other relatively better performing states in case detection are Maharashtra (one in 12 infections) and Karnataka (one in 16 infections). Low case detection has been estimated for Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, where one in nearly every 80-134 cases gets picked up (see table). The pace of COVID-19 vaccination is also faster in Kerala and the state has a far bigger proportion of its population either fully or partially vaccinated than the national average.

What Kerala Can Do Better

Reporting nearly half of India’s daily COVID-19 cases does raise an alarm. However, merely examining the pooled numbers, generated from variably performing disease surveillance systems, would be erroneous and simplistic. The last three columns in the table would explain that Kerala accounts for nearly 10 per cent of the estimated daily infections in the country [3] (still proportionately higher than the state’s population).

But there are things which Kerala has not done right. It has regularly allowed large gatherings, including Onam in 2020 and campaigns for Assembly election in early 2021, and relaxed restrictions for a religious festival as late as mid-July 2021. Some of these gatherings have resulted in an increase in the transmission rate and consequently a rise in cases. Clearly, there is a need to learn from mistakes of the past and errors made by others. As long as there is sustained transmission, Kerala (and other Indian states) have to stop any such gathering at all costs, including during the forthcoming Onam festival.

Targeted Strategies

In 2020 and early 2021, a few countries such as Thailand and Vietnam and the Indian state of Kerala were considered models for their pandemic response. Currently, all of them and many others are staring at a fresh rise in COVID-19 cases and facing challenges in containing the spread. Last 17 months of the pandemic have taught us one thing: no country or state can claim to be a model until the pandemic is over, globally. Every state and every country needs to continuously learn from others and do more. Kerala, with the largest proportion of susceptible population, definitely has to do more.

First, the state needs to develop a more nuanced and dynamic ‘containment and unlock’ strategy, with use of local epidemiological parameters (state is generating a lot of useful surveillance and testing data). The implementation of strategy should be facilitated by active engagement of community members and local bodies.

Second, launch fresh communication drives/ campaigns to improve adherence to COVID-appropriate behaviours (CAB), including implementing additional strategies such as free mask distribution.

Third, with a relatively low seroprevalence and ongoing transmission, the pace of COVID-19 vaccination in Kerala needs to be accelerated with the purpose of reducing both transmission and mortality[4]. For this, the union and state governments should work to secure more vaccines and ensure accelerated roll-out.

All three strategies should be implemented in a targeted manner, in settings of high and sustained transmission with a localized approach.

Conclusion

The high number of reported daily COVID-19 cases and test positivity rate in Kerala are likely due to a better performing disease surveillance system and targeted testing strategy. Therefore, comparing Kerala’s numbers with other states with relatively weak disease surveillance systems would result in erroneous interpretation.

India is still in the middle of the pandemic, with the virus circulating in all states and there are projections of a third wave. Therefore, every Indian state irrespective of the status of transmission should continue to implement response strategies, investigate the reasons for sustained transmission or rise in the cases beyond daily reported numbers, and must learn from each other. That’s what would guide India to win against the COVID-19 pandemic.

[1] In Fourth national seroprevalence survey, the data was collected in end June and early July 2021 from 70 districts of 21 states. These were the same states where previous three rounds of surveys were conducted. It was found that 67.6% of surveyed population (or an estimated 90 crore of India’s population) had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Although the survey methodology was designed to provide reliable estimates for national levels, the state level estimates have also been released. The state specific data has to be read with caution and has limitations as the sample size and sampling strategy were not enough to provide robust state level estimates and is likely to have provided a wide confidence interval. However, since a similar method had been adopted for all states, comparison is possible (but, with the limitations). Such standard disclaimers are applicable to the table in this article.

[2] A few argue that Kerala’s case fatality rate is low due to under-reporting of deaths. However, a number of subject experts and Indian journalists have done analysis of excess mortality through civil registration system data. They have calculated that ‘excess mortality’ for Kerala is around 1.6 times, against an estimated ‘excess mortality’ of up to 30 to 40 times for many other states.

[3] As the fourth national sero-survey notes, the national average is ~30 undetected cases for every case officially reported. Therefore, 40,000 daily reported COVID-19 cases translate into an estimated 1,200,000 COVID-19 infections per day. For Kerala, the case to infection ratio is around 6. Therefore, when the state reports 20,000 cases, actual infections in the state are likely to be 120,000. Therefore, Kerala would account for 10% of total daily infections. Because of better performing disease surveillance and reporting systems, it is reporting more cases, officially.

[4] In India, the main objective of COVID-19 vaccination is to reduce hospitalization and mortality, thus the high risk population is being prioritized. However, as the vaccine coverage increases, the purpose also shifts to reducing transmission and thus prioritizing vaccination for people who are likely to transmit the disease. With high vaccine coverage and sustained transmission, Kerala requires a blended approach.

Dr Lahariya is a physician and epidemiologist. He writes a fortnightly column HealthHacks for News18 and can be reached @DrLahariya. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Union Budget 2022 updates here.

Comments

0 comment