views

At a time when India is witnessing a debate on nationalism, Professor Sekhar Bandyopadhyay, who has authored several books on Indian freedom movement, including ‘From Plassey to Partition: A History of modern India’, which is considered to be a ‘definitive account’ of the freedom struggle, talks to News18 about various aspects of the revolt. In an email interaction on the eve of 160th anniversary of the first war for Independent India, the historian and philosopher who teaches at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, says the revolt teaches us that Indian nationalism should be based on Hindu-Muslim unity. Edited excerpts:

Seeds of Indian freedom struggle were sown much before the revolt of 1857. Why do historians call it the first war of Independence?

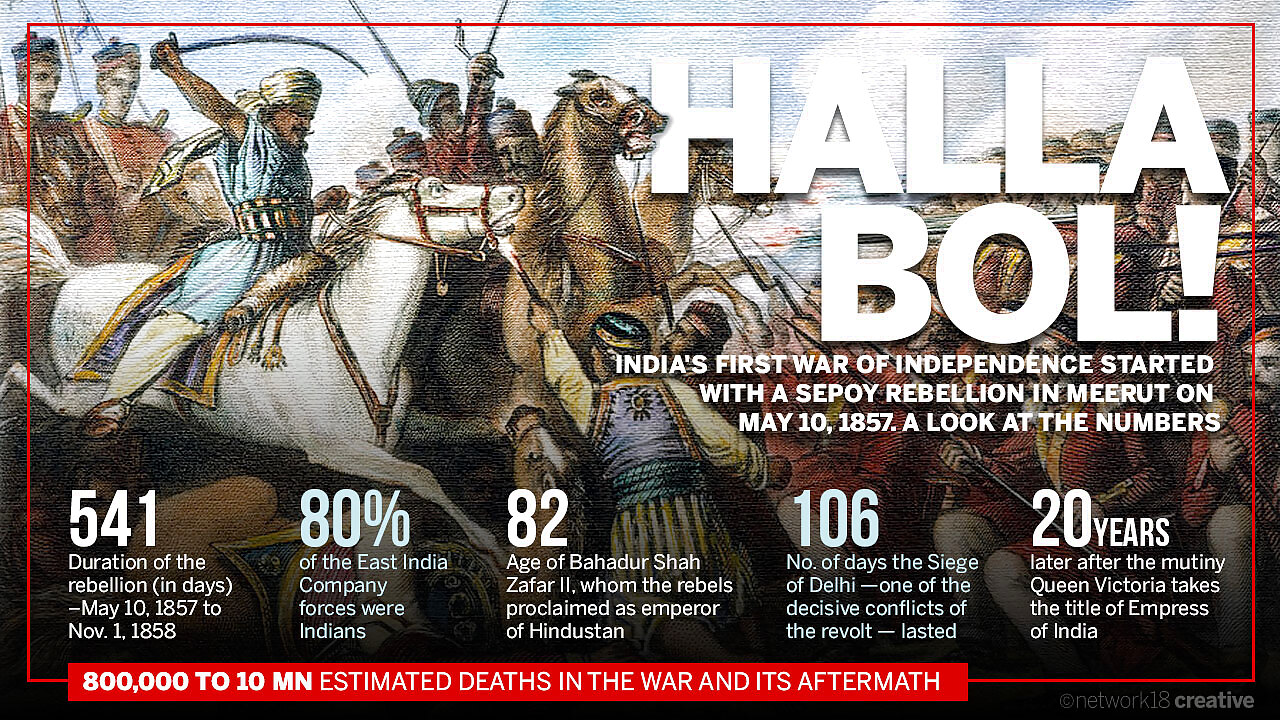

There were popular movements against British rule that took place before 1857, but they were not for ‘independence’, but against specific oppressive aspects of the rule or against specific policies. And they were also localised movements. In 1857, we first time witnessed popular unrest in a large part of north India, aiming specifically to overthrow the British rule.

When one looks at the scale of the revolt, it was spread across vast regions. How was such a huge secret operation pulled off without modern means of communication?

The discontent against East India Company’s rule had been developing for a long period of time and over a large region. It was an open revolt with an element of spontaneity, but social mobilisation was taking place for a long time. A large segment of the Indian population was angry and when the sepoys revolted, they received the sympathy of the civilian population with whom they had family and kinship ties. So the mutiny soon turned into a civilian revolt. Whenever the rebel sepoys came to a village they were joined by the already aggrieved peasants.

What according to you was the most important cause of the rebellion?

It was caused by a general dissatisfaction with the policies and administration of the East India Company’s government. In general, there was also discontent about the activities of the Christian missionaries. Different segments of the population had different specific grievances. The soldiers had grievances against their service rules, and a distrust about the ulterior motives of the army administration. Peasants were aggrieved by the oppressive revenue system of the Company’s government… The sepoys were 'peasants in uniform', or in other words, had close ties with the peasant communities. So when they rose in revolt others joined them… Aristocrats and indigenous rulers were aggrieved because of confiscation of their estates. So all the causes combined to create such a conflagration.

Extraordinary violence took place on both sides during the mutiny and even women and children were not spared. Do you think the mutiny lacked a moral character?

It is difficult to judge the morality of the situation. Violence was perpetrated on both sides. But first there was the day-to-day experience of state violence that the Indian people faced because of a heartless profit making alien regime. Until 1857, the colonial state had a monopoly of violence, but now the rebels retorted with an equal amount of counter-violence. Both insurgency and counter-insurgency were equally indiscriminately violent. But before judging the morality of this violence, we need to look at the moral foundation of the colonial state itself.

Was the blood spilled during the mutiny a proof that for a vast and complex country like India, a leader like Mahatma Gandhi was needed to take the freedom struggle forward in a largely peaceful manner?

The revolt of 1857 failed to drive away the British not because of violence, but because of lack of organisation, ideological coherence and a vision about the future on the part of the rebels.

Oxford Dictionary has a slang ‘pandy’, meaning traitor. Though the word is now obsolete, could you please tell us about how it came into being?

The mutiny was triggered by a sepoy called Mangal Pande in the Bengal Army in Barrackpore on March 29, when he fired at a European officer and his comrades refused to arrest him. Later on they were apprehended, court martialled and hanged. Following this, the mutiny was started in Meerut on May 10. The British public look at this revolt as an act of betrayal. And Mangal Pande — or 'Pandy' as he was probably called by European officers — became the symbol of such treacherous Indians who were being ungrateful.

The Roti Rebellion is quite popular in the storytelling tradition of India. However, not many know about the facts and circumstances. Could you please throw some light on it?

The revolt began to spread rapidly over a wide region without any reported prior planning. So there is the mythical story of ‘chapati’ or an Indian bread circulating and spreading the message of rebellion. Historians are not certain as to what exact message the chapatis used to convey when they were carried from one village to the other. There is lot of speculation on this. Probably it carried the message that some kind of bad time was coming.

There a debate around nationalism in today’s India. What could be the lessons from 1857 for this debate? Have we, as a society, failed to learn from history?

One major feature of 1857 revolt was the remarkable unity between the Hindus and Muslims during that period of turmoil. Sepoys and civilian rebels from both communities fought side by side to take back their country from alien rule and respected each other’s religion. It should teach the lesson that Indian nationalism should be based on Hindu-Muslim unity.

Comments

0 comment