views

Ayodhya: Every day for the last two decades, Rajnikat Sompura has been slowly chipping away at massive slabs of Dholpur stone. The work is painstaking, and each elaborate carving is both — a labour of love and a matter of faith. He hopes these slabs will one day be part of the ceiling of the Ram Mandir that Hindu organizations have been clamoring to build in Ayodhya for over 70 years.

This workshop is owned by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and it pays Sompura Rs 12,000 a month. His work has made him a bit of a local celebrity. His life is etched in the intersection of politics and religion.

“This is my livelihood. I am living in God’s city, I consider myself lucky. There are no companies here, so people earn a living by selling religious books or prasad. God has made a good system here in Ayodhya, everyone gets by. Even the monkeys get by fine,” he says.

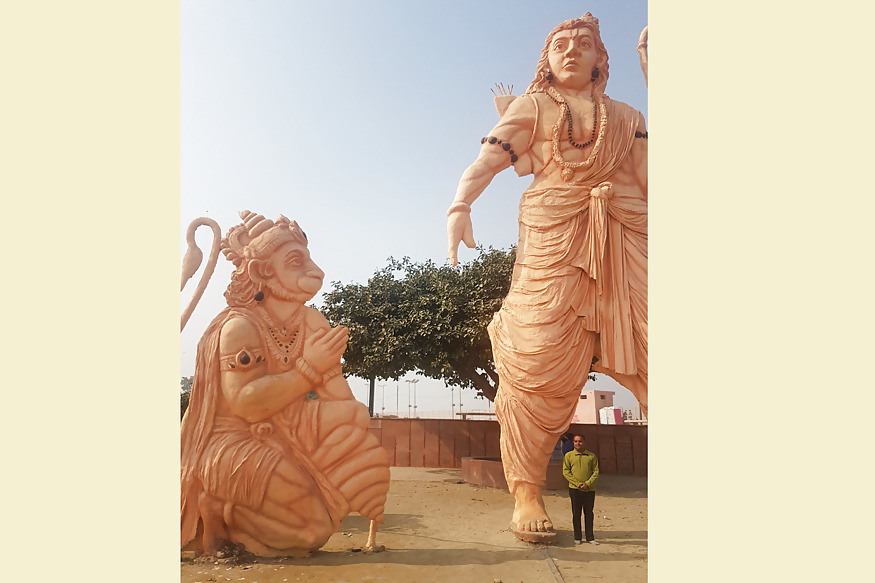

Ayodhya is a small town of about 80,000 people in the heart of UP’s Awadh region. Hindus believe Lord Ram, the revered Hindu deity, was born here. This location was also the site of the Babri Masjid, which was demolished by supporters of the Hindu Right in 1992.

The movement to restore that land to a Ram Janmabhoomi temple has made Ayodhya the epicenter of Hindutva politics. With an overwhelming 93% Hindu majority, the town has become synonymous with the Ram Mandir, or lack thereof. City residents suggest that the Ram Mandir will lead them to Ram Rajya.

“Ayodhya residents have not received any benefit. If Ram Mandir is built, they will feel everything was worth it. What did Ayodhya residents get? They got nothing,” says Sitaram Das, 72-year-old priest of a local temple.

VHP’s Ayodhya district spokesperson Sharad Sharma goes a step further and says the disputed site must be “liberated” for Hindus. “Our saints have given a slogan — bring a law, construct the Mandir. Ram Janmbhoomi must be given ‘mukti’ (liberation), just like Somnath was given ‘mukti’. Ram Lalla must move from under the tent to a grand temple. The stones are being carved for that purpose too.”

26 years ago, a mob converged at Ayodhya main public crossing – the Tedhi Bazaar Chauraha — and marched along to the Babri Masjid, which was demolished in a matter of hours. In the years that followed, the Ram Mandir movement saw many ebbs and flows. People come here from all parts of the country to find Ram. But in all these years, through all the politics, has Ayodhya found Ram Rajya?

Locals believe that the wheels of vikas or development that have been stuck for far too long in this sleepy town have now started to move. Last year, the Yogi Adityanath government announced the creation of Ayodhya Nagar Nigam. This gives the local representatives more autonomy and a higher budget for the city. Elections were held last December and Rishikesh Upadhyay of the BJP was sworn in as the first mayor of Ayodhya on December 14, 2017.

“I have been Mayor for a year. In the last year, Ayodhya has changed a lot. The entire city is lit up with LED lights. Roads have improved. Ram Paidi and Ram Katha Park have been improved. The CM has also passed the tender to treat the water of the five drains that were dirtying the Saryu,” the mayor says.

Manoj Kumar Gupta, a local trader, agrees. “There has been a lot of change in the last two years. When we were young, there was no electricity even during Diwali. Now, we have electricity and water. The police are always alert here. The beginning has been good and will always be slow. Things have happened on the main road and main areas and soon the government will work in the streets as well.”

The one thing that most people seem to agree on is that, for better or for worse, Ayodhya has come in to focus since Yogi Adityanath became Chief Minister. The ‘Ram ki Paidi’ Ghat, for example, was re-developed before the Deepotsav in November. But that hasn’t necessarily meant sweeping changes or that everyone happy.

Behind the banks of the Saryu, where the ‘Ram ki Paidi’ ghat was lit up for Diwali, is a locality called ‘Swargdwar’ that translates roughly to ‘the 'Gates to Heaven’. But the conditions are far from heavenly. Even the most basic utility like a toilet is hard to find here. The councilor for Swargdwar is 23-year-old Mahendra Shukla of the Samajwadi Party. He says the BJP’s “development” of Ayodhya is only skin–deep. “The ward where Deepotsav was celebrated is called Swargdwar, I am the coucillor from that ward. In most lanes, it is still dark. The condition of roads is very bad inside the city. Whenever a VIP comes to Ayodhya, they don’t go to the bylanes. Only those places were developed where the CM was standing during Deepotsav. Only those temples were painted which were covered by cameras. The situation on the main road is the opposite of what you will see in the bylanes.

Archana Tiwari, a Swargdar resident, says women in particular bear the brunt of a lack of facilities. “This locality is called Swargdwar (Gates of heaven), but it looks nothing like it. Things here are very bad because people don’t have basic facilities. There are no toilets, no employment. Almost the entire locality is without toilets. When people have to use the toilet, they go to an abandoned mosque because there is no facility. There is no guarantee that this mosque won’t fall on our heads.”

Only six per cent of Ayodhya's residents are Muslims. Some of them have considered leaving the city, but have found it difficult to leave their ancestral homes. Irshad Ali, a septuagenarian businessman, says, “There were times when I thought of packing up and leaving, but the children decided that we would not move out of Ayodhya. Jo Sukoon Ayodhya mein hai, who bahar jaane ke baad na ke barabar ho jayega. (The peace of mind I find in Ayodhya will vanish if I leave). Here, people are always ready to help us. You see that this fight for Janmabhoomi (birthplace) is so fierce. How can we forget our Janmabhoomi?”

The Ali family has lived in Ayodhya for generations. The father-son duo, Irshad and Ehsaan Ali, run a mechanical parts workshop in neighboring Faizabad. They speak of their double dilemma – running a business in a district known for curfews and living as Muslims in the heart of Hindutva politics.

“Every year around the anniversary of the Babri Masjid demolition, rumors spread that Ayodhya is under curfew. The roads are sealed and people who could come here for business go to other districts like Sultanpur, Basti and Gonda. Business is affected badly,” says Ehsaan Ali, the son.

Irshad Ali adds, “Temples and mosques will not bring development. Let the court decide (on the question of the disputed site). You (Hindus) follow it and so will we (Muslims). Let it be built after that. Then maybe the focus will be on development. When people are not afraid, they will bring their business to Ayodhya.”

But for supporters of the Mandir, it’s more than just a matter of faith. A Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, they say, could also be a driver for growth. “If a Mandir is built, the growth in Ayodhya will skyrocket. Investors will come here from everywhere,” says Mayor Rishikesh Upadhyay.

Manoj Kumar Gupta adds, “If a Mandir is built, it will be like gold for us. Our economy will grow so much, nobody here will lack anything.”

The problems of Ayodhya are not unlike any other small town in UP. Employment, clean surroundings and a good future for their children – that’s all they want. But what sets this town apart is if they can manage to achieve high living standards and model governance they will have lived up to being the ancient city of Ayodyhya where Ram once ruled and created a kingdom that epitomized good governance or Ram Rajya.

Comments

0 comment