views

Getting Started

Have a separate notebook for social studies. It can be confusing when you have all of your notes from all your subjects crammed into one notebook. So you might want to think about having a separate notebook for Social Studies so it doesn't get mixed up with your Math and Science notes.

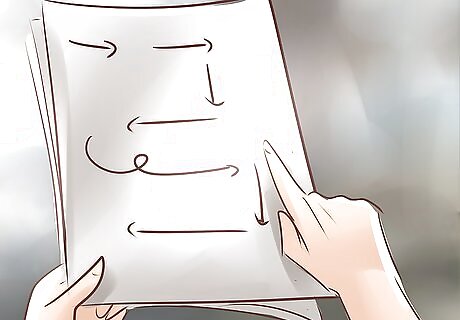

Start a brand new page for a new topic. It doesn't matter if the last section stopped halfway through a page, that subject of notes has ended and you need to start a new page. This will prevent any confusion about what subject is what when going back to your notes to study off of later. When a subject is continued onto a new piece of paper, add the word continued next to the title. For example, "The Civil War Continued." And make sure you title your page at the right-hand side of your paper and date it on the left-hand side of your paper. Use an arrow-preferably in a different color, such as red (which works the best)- at the bottom of your page to indicate that your notes are continued onto the next page. And always, always, always use the back of your paper, not only will it save trees, but it will also save money too. And who doesn't want to save money?

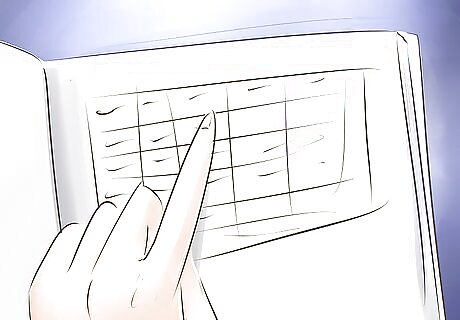

Choosing a note-taking method. Taking notes isn't inscribed in ancient text, and there is no right way to take notes. But there is a more efficient way depending on where you taking notes from, such as a lecture, book, or textbook. There are four good ways to take notes and they are: An outline. An outline is good for when you taking notes in class because you have an organized format to layout subheadings, key concepts, keywords. vocabulary, details, summaries, etc. Cornell Method. The Cornell Method is a good note-taking strategy for taking notes during a lecture because of the way it is designed. The Cornell Method divides your paper into three sections: the "Cue Column", the "Note-Taking Section", and the "Summary Row". The Cue Column is written before class because this is where you write any questions you may have, anything you do not understand, and for key details. The Note-Taking is taken during class, this is where you write all your notes. and the Summary Row is written after class because you will summarize everything in the Note-taking Section and the Cue Column. The "T" Method. The "T" Method is good for when you are taking notes in class because of the way it is formatted. The "T" Method divides your page into two sections instead of three like the Cornell Method. The right-hand side is used for subheadings and key concepts of that subheading. And the left-hand side is used for expanding your notes in the right-hand side. The SQ3R Method.The SQ3R is a useful note-taking method for taking notes from a textbook because it makes you really think and comprehend what the text is about. SQ3R stand for: S.urvey, Q.uestion, 3 or the three R's R.ead: R.ecite, and R.eview. Mindmapping. This note-taking method is good for taking notes on a book, textbook, or lectures/in-class discussions. Mindmapping is a good note-taking method for visual learners because it is a way to visualize your notes.

Taking Notes During a Lecture or a Textbook

Use SQ3R. SQRRR or "SQ3R" is a reading comprehension method named for its five steps: the survey, question, read, recite, and review. The method was introduced by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1946 book Effective Study. The method, created for college students, can also be used by elementary school students, who can practice all of the steps once they have begun to read longer and more complex texts. Similar methods developed subsequently include PQRST and KWL table. Survey. The first step, survey or skim, advises that one should resist the temptation to read the book and instead glance through a chapter in order to identify headings, sub-headings and other outstanding features in the text. This is in order to identify ideas and formulate questions about the content of the chapter. Question. Formulate questions about the content of the reading. For example, convert headings and subheadings into questions, and then look for answers in the content of the text. Other more general questions may also be formulated: What is this chapter about?" "What question is this chapter trying to answer?" "How does this information help me?" Read. Use the background work done with "S" and "Q" in order to begin reading actively. This means reading in order to answer the questions raised under "Q". Passive reading, in contrast, results in merely reading without engaging with the study material. The second "R" refers to the part known as "Recite/wRite" or "Recall." Using key phrases, one is meant to identify major points and answers to questions from the "Q" step for each section. This may be done either in an oral or written format. It is important that an adherent to this method use his/her own words in order to evoke the active listening quality of this study method. The final "R" is "Review." In fact, before becoming acquainted with this method a student probably just uses the R & R method; Read and Review. Provided the student has followed all recommendations, the student should have a study sheet and should test himself or herself by attempting to recall the key phrases. This method instructs the diligent student to immediately review all sections pertaining to any keywords forgotten.

Make a timeline. A timeline is a way of displaying a list of events in chronological order, sometimes described as a project artifact. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labelled with dates alongside itself and usually events labeled on points where they would have happened. Timelines can use any time scale, depending on the subject and data. Most timelines use a linear scale, where a unit of distance is equal to a set amount of time. This time scale is dependent on the events in the timeline. A timeline of evolution can be over million of years whereas a timeline for the day of the September 11 attacks can take place over minutes. While most timelines use a linear timescale, for very large or small time spans, logarithmic timelines use a logarithmic scale to depict time. There are many methods of visualizations for timelines. Historically, timelines were static images and generally drawn or printed on paper. Timelines relied heavily on graphic design, and the ability of the artist to visualize the data. In historical studies, timelines are particularly useful for studying history, as they convey a sense of change over time. Wars and social movements are often shown as timelines. Timelines are also useful for biographies. Examples include: Timeline of the American Civil Rights Movement Timeline of European exploration Timeline of imperialism Timeline of Solar System exploration Timeline of United States history Timeline of World War I Timeline of religion

Paraphrase. A paraphrase is a restatement of the meaning of a text or passage using other words. The term itself is derived via Latin from Greek, meaning "additional manner of expression". The act of paraphrasing is also called "paraphrasis". A paraphrase typically explains or clarifies the text that is being paraphrased. For example, "The signal was red" might be paraphrased as "The train was not allowed to pass because the signal was red". A paraphrase is usually introduced with a declaratory expression to signal the transition to the paraphrase. For example, in "The signal was red, that is, the train was not allowed to proceed," the that signals the paraphrase that follows. A paraphrase does not need to accompany a direct quotation, the paraphrase typically serves to put the source's statement into perspective or to clarify the context in which it appeared. A paraphrase is typically more detailed than a summary. One should add the source at the end of the sentence, for example: When the light was red trains could not go. A paraphrase may attempt to preserve the essential meaning of the material being paraphrased. Thus, the reinterpretation of a source to infer a meaning that is not explicitly evident in the source itself qualifies as "original research," and not as a paraphrase.

Summarize. Summarizing a text, or distilling its essential concepts into a paragraph or two, is a useful study tool as well as good writing practice. A summary has two aims: (1) to reproduce the overarching ideas in a text, identifying the general concepts that run through the entire piece, and (2) to express these overarching ideas using precise, specific language. When you summarize, you cannot rely on the language the author has used to develop his or her points, and you must find a way to give an overview of these points without your own sentences becoming too general. You must also make decisions about which concepts to leave in and which to omit, taking into consideration your purposes in summarizing and also your view of what is important in this text. Include the title and identify the author in your first sentence. The first sentence or two of your summary should contain the author’s thesis, or central concept, stated in your own words. This is the idea that runs through the entire text--the one you’d mention if someone asked you: “What is this piece/article about?” Unlike student essays, the main idea in a primary document or an academic article may not be stated in one location at the beginning. Instead, it may be gradually developed throughout the piece or it may become fully apparent only at the end. When summarizing a longer article, try to see how the various stages in the explanation or argument are built up in groups of related paragraphs. Divide the article into sections if it isn’t done in the published form. Then, write a sentence or two to cover the key ideas in each section. Omit ideas that are not really central to the text. Don’t feel that you must reproduce the author’s exact progression of thought. (On the other hand, be careful not to misrepresent ideas by omitting important aspects of the author’s discussion). In general, omit minor details and specific examples. (In some texts, an extended example may be a key part of the argument, so you would want to mention it). Avoid writing opinions or personal responses in your summaries (save these for active reading responses or tutorial discussions). Be careful not to plagiarize the author’s words. If you do use even a few of the author’s words, they must appear in quotation marks. To avoid plagiarism, try writing the first draft of your summary without looking back at the original text.

Omit words. In your notes, write only necessary words. Never write words like "the" or "a" or any conjunction ("and" or "but") or simple prepositions ("near" "at"). You can assume these words in the context of what you write. Omit only standard and obvious words.

Use abbreviations and symbols. Abbreviate all words you can, but make sure your abbreviations are standardized and obvious. Always use the same abbreviation for the same word, and make a list of those abbreviation somewhere, like the inside cover of your notebook. After a while, you will need to refer to this list only to add new abbreviations. Make generous use of whatever symbols you wish. Obvious choices might be a slash (/) when you want to compare two things, w/ for "with"; or if you think you need to use the word "and" somewhere, use an ampersand (&) instead of the entire word. Other symbols might include such things as @ for "at", # for "number", or math signs (i.e. "+" for "also").

Revise and edit your notes. When you get home from class take out your notes and revise and edit them. This is time to color-code, highlight, underline, circle, etc. your notes. This is also when you can do research on things you didn't understand and expand on it if it’s going to be on an exam.

Study your notes every day. If you study your notes for 5-10 minutes a day you will improve your test score because you're rock solid on the material. It has been studied by many people, and at the end of each study has shown that students who study their notes every night for 5-20 minutes a day improve their grade.

Comments

0 comment