views

Writing and Development

Choose a worthy topic. What will your film be about? Your documentary should be worthy of your audience's time (not to mention your own). Make sure your topic isn't something mundane or universally agreed-upon. Try instead to focus on subjects that are controversial or not-well known, or try to shed new light on a person, issue, or event that the public has largely made its mind up about. In simplest terms, try to film things that are interesting and to avoid things that are boring or ordinary. This doesn't mean your documentary has to be huge or grandiose - smaller-scale, more intimate documentaries have just as much of an opportunity to resonate with an audience if the story they tell is captivating.

Find a topic you are interested in that will also be engaging and enlightening for your audience. Try out your ideas in verbal form first. Start telling your documentary idea in story form to your family and friends. Based on their reaction, you may do one of two things; scrap the idea completely or revise it and move forward. Though documentaries are educational, they still have to hold the audience's attention. Here, a good topic can do wonders. Many documentaries are about controversial social issues. Others are about past events that stir up strong emotions. Some challenge the things that society views as normal. Some tell the story of individual people or events to make conclusions about larger trends or issues. Whether you choose one of these approaches or not, make sure you pick a subject with the potential to hold an audience's attention. For instance, it would be a bad idea to create a documentary about everyday life in a random small town unless you're really confident you can make the lives of ordinary people interesting and meaningful in some way. A better idea would be to make a documentary that casts the daily life of this small town against the story of a grisly murder that took place there, showing how the town's inhabitants were affected by the crime.

Give your film a purpose. Good documentaries almost always have a point - a good documentary may ask a question about the way our society operates, attempt to prove or disprove the validity of a certain point of view, or cast light on an event or phenomenon unknown to the general public in hopes of spurring action. Even documentaries about events that happened far in the past can draw connections to the world today. Despite its name, the purpose of a documentary isn't just to document something that occurred. The objective of a documentary shouldn't just be to show that something interesting occurred - a really good documentary should persuade, surprise, question, and/or challenge the audience. Try to show why an audience should feel a certain way about the people and things you're filming. Acclaimed director Col Spector says that, along with not choosing a worthy subject, not asking any serious questions and not choosing an overriding theme are two of the most serious mistakes a documentary filmmaker can make. Says Spector: "Before filming, ask yourself, what question am I asking and how does this film express my worldview?"

Research your topic. Even if you're familiar with your topic it's still a very smart idea to research it extensively before you begin filming. Read about your topic as much as you can. Watch films about your topic that already exist. Use the Internet and any library you have access to to find information. Most importantly, talk to people who know about or are interested in your subject - the stories and details that these people provide will guide the plan for your film. Once you've decided on a general topic you are interested in, use your research to help you narrow your topic down. If, for instance, you are interested in cars, pinpoint people, events, processes, and facts relating to cars that you come across in your research that specifically interest you. For example, your may narrow down a documentary about cars to one about a specific group of people who work on classic cars and gather to show them off and talk about them. Narrowly-focused documentaries are often easier to film and sometimes easier to make compelling to an audience. Learn as much as you can about the subject and scope out the landscape to see if there is already a documentary or media project out there. Wherever possible, you want your documentary and approach to the subject to be different than anything that might also be out there. Do a few pre-interviews based on your research. This allows you the opportunity to start developing a story idea with main subject perspectives.

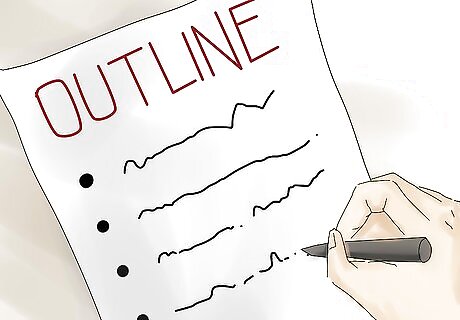

Write an outline. This is very handy for project direction and possible funders. The outline also gives you an idea of story, as your project must be story-driven with all the elements of a good story. In the outline process, you should also explore the conflict and drama that you will need to keep the story alive as it unspools.

Staff, Techniques and Scheduling

Recruit a staff, if necessary. It's entirely possible for one person to research, plan, shoot, and edit a documentary by themself, especially if the documentary's scope is relatively small or intimate. However, many may find this "one person, one camera" approach to be exceedingly difficult or to result in amateurish, unpolished footage. Consider hiring or recruiting experienced help for your documentary, especially if you're tackling an ambitious topic or you want your film to have a polished, professional quality. To get help, you may try recruiting qualified friends and acquaintances, advertising your project via flyers or online postings, or contacting a talent agency. Here are just a few types of professionals you might consider employing: Cameramen Lighting riggers Writers Researchers Editors Actors (for scripted sequences/recreations) Audio recorders/editors Technical consultants. Steven Spielberg Steven Spielberg, Film Director Learn to appreciate and rely on your collaborators. "Filmmaking is all about appreciating the talents of the people you surround yourself with and knowing you could never have made any of these films by yourself."

When hiring or recruiting your team, look for people who share similar values when it comes to the subject matter of the documentary. Also consider hiring young up-and-coming crew who are inspired and in touch with markets and audiences you may have overlooked. Always confer with your camera op and other creative folks involved in the documentary. This helps make your docs a collaborative effort, with a shared vision. Working in a collaborative environment means that you'll often find your crew seeing something and contributing to the project in ways you may have overlooked.

Learn basic film making techniques. Serious documentary film makers should, at the very least, understand how films are produced, staged, shot, and edited, even if they can't do all of these things by themselves. If you're unaware of the technical process behind making films, you may find it worthwhile to study film making before shooting your documentary. Many colleges and universities offer film making courses, but you can also get practical experience by working around film sets either in front of or behind the camera. Though many directors have a film school background, practical knowledge can trump a formal film making education. For instance, comedian Louis C.K., who has worked as a director in film and television, got early film making experience by working at a local public access station.

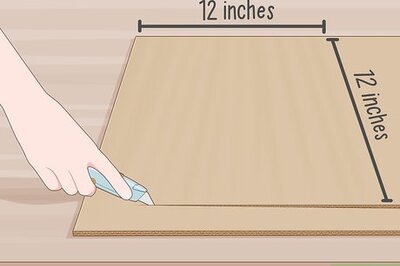

Get equipment. Try to use the best quality media available (high end cameras etc.). Beg or borrow equipment you can't otherwise afford, and use your contacts to get access to subjects and equipment.

Organize, outline, and schedule your shooting. You don't necessarily need to know exactly how your documentary is going to come together before you start shooting - you may discover things during the process of filming that change your plans or offer new avenues of investigation. However, you should definitely have a plan before you start shooting, including an outline of specific footage you want to shoot. Having a plan ahead of time will give you extra time to schedule interviews, work around scheduling conflicts, etc. Your plan for shooting should include: Specific people you want to interview - make contact with these people as early as possible to schedule interviews. Specific events you want to record as they occur - arrange travel to and from these events, buy tickets if necessary, and get permission from the event's planners to be able to shoot at the event. Specific writings, pictures, drawings, music, and/or other documents you want to use. Get permission to use these from the creator(s) before you add them to your documentary. Any dramatic recreations you want to shoot. Search for actors, props, and shooting locations well ahead of time.

Shooting a Documentary

Interview relevant people. Many documentaries devote much of their running time to one-on-one interviews with people who are knowledgeable about the subject of the documentary. Pick a selection of relevant people to interview and collect as much footage as you can from these interviews. You'll be able to splice this footage throughout your documentary to help prove your point or convey your message. Interviews can be "news style" - in other words, simply sticking a microphone in someone's face - but you'll probably want want to rely more on one-on-one sit-down interviews, as these give you a chance to control the lighting, staging, and sound quality of your footage while also allowing your subject to relax, take Their time, tell stories, etc. These people may be famous or important - well-known authors who have written about your subject, for instance, or professors who have studied it extensively. However, many of these people may not be famous or important. They may be ordinary people whose work has given them a familiarity of your subject or people who simply witnessed an important event firsthand. They can, in certain situations, even be completely ignorant of your subject - it can even be enlightening (and entertaining) for the audience to hear the difference between a knowledgeable person's opinion and an ignorant person's opinion. Let's say our car documentary is on classic car aficionados in Austin, Texas. Here are just a few ideas for people to interview: members of classic car clubs in and around Austin, wealthy car collectors, cranky old people who have complained to the city about the noise from these cars, first-time visitors to a classic car show, and mechanics who work on the cars. If you're stumped for interview questions, brainstorm questions based on the basic queries "who?" "what?" "why?" "when?" "where?" and "how?" Often, asking someone these basic questions about your subject will be enough to get them to relate an interesting story or some enlightening details. Remember––a good interview should be more like a conversation. As the interviewer, you must be prepared, having done your research and informed yourself to glean the most information from the interview subject. Grab B-roll whenever possible. Get shots of your interview subject after the formal interview. This allows you to cutaway from the talking head shot.

Get live footage of relevant events. One of the main advantages of documentary films (as opposed to dramatic films) is that they allow the director to show the audience real footage of actual real-life events. Provided you don't break any privacy laws, get as much real-world footage as you can. Film events that support your documentary's viewpoint, or, if the subject of your documentary happened in the past, get in touch with agencies or people who have historical footage to get permission to use it. For instance, if you're making a documentary on police brutality during the Occupy Wall Street protests, you may want to contact people who participated in the protests and collected hand-held footage. In our car documentary, we'd obviously want lots of footage of classic car expos taking place in and around Austin. If we're creative, though, there are plenty of other things we might want to film: a town hall discussion on a proposed car show ban, for instance, might provide some thrilling dramatic tension.

Film establishing shots. If you've watched a documentary before, you've surely noticed that the entire movie isn't just footage of interviews and of live events with nothing in between. For instance, there are often shots leading into interviews that establish a mood or show where the interview is taking place by showing the outside of the building, the city skyline, etc. These are called "establishing shots," and they're a small but important part of your documentary. In our car documentary, we'd want to film establishing shots at the locations where our interviews took place: in this case, classic car museums, chop shops, etc. We might also want to get some footage of downtown Austin or of distinct Austin landmarks to give the audience a sense of the locale. Always collect audio from the shoot including room tone and sound effects unique to that location.

Film B-roll. In addition to establishing shots, you'll also want to get secondary footage called "B-roll" - this can be footage of important objects, interesting processes, or stock footage of historical events. B-roll is important for maintaining the visual fluidity of your documentary and ensuring a brisk pace, as it allows you to keep the film visually active even as the audio lingers on one person's speech. In our documentary, we'd want to collect as much car-related B-roll as possible - glamorous close-ups of shiny car bodies, headlights, etc., as well as footage of the cars in motion. B-roll is especially important if your documentary will make use of extensive voiceover narration. Since you can't play the narration over interview footage without keeping the audience from hearing what your subject is saying, you'll usually lay the voiceover over short stretches of B-roll. You can also use B-roll to mask the flaws in interviews that didn't go perfectly. For instance, if your subject had a coughing fit in the middle of an otherwise great interview, during the editing process, you can cut the coughing fit out, then set the audio of the interview to B-roll footage, masking the cut.

Shoot dramatic recreations. If there's no real-life footage of an event your documentary discusses, it's acceptable to use actors to re-create the event for your camera, provided the recreation is informed by real-world fact and it's perfectly clear to the audience that the footage is a recreation. Be reasonable with what you film as a dramatic recreation - make sure that whatever you commit to film is grounded in reality. Sometimes, dramatic recreations will obscure the actors' faces. This is because it can be jarring for an audience to see an actor portray a real-world person in a film that also contains real footage of them. You may want to film or edit this footage in a way that gives it a visual style distinct from the rest of your film (for instance, by muting the color palette). This way, it's easy for your audience to tell which footage is "real" and which is a recreation.

Keep a diary. As you film your documentary, keep a diary of how the filming went each day. Include any mistakes you made as well as any unexpected surprises you encountered. Also consider writing a brief outline for the next day of shooting. If an interview subject said something that makes you want to pursue a new angle for your film, note this. By keeping track of each day's events, you have a better chance of keeping on track and on schedule. Once finished, do a paper edit viewing footage and making notes of shots to keep and others to discard.

Assembling and Sharing

Make a new outline for your finished film. Now that you've collected all the footage for your documentary, you need to organize it in an order that is interesting, coherent, and will keep the viewers' attention. Make a detailed shot-by-shot outline to guide the editing process. Provide a coherent narrative for the audience to follow that proves your viewpoint. Decide which footage will go at the beginning, which will go in the middle, which will go at the end, and which won't go in the film at all. Showcase the most interesting footage, while cutting anything that seems meandering, boring, or pointless. In our classic car documentary, we might start with exciting or amusing ride-along footage to ease the viewers into the world of classic car aficionados. We'd then dive into the opening credits, followed by interview footage, clips from car shows, etc. The end of your documentary should be something that ties the film's information together in an interesting way and reinforces your key theme - this can be a striking final image or a great, memorable comment from an interview. In our car documentary, we might choose to end on footage of a beautiful classic car being scrapped for parts - a commentary on the fact that appreciation for classic cars is dying.

Record a voiceover. Many documentaries use audio narration as a running thread throughout the film, linking the film's interview and real-life footage in a coherent narrative. You can record a voiceover yourself, enlist the help of a friend, or even hire a professional voice actor. Make sure your narration is clear, concise, and understandable. Generally, an audio voiceover should play over footage where the audio isn't important - you don't want the audience to miss anything. Lay your voiceover over establishing shots, B-roll, or real-life footage where the audio isn't necessary to grasp the importance of what's going on.

Create graphical/animated inserts. Some documentaries use static or animated graphics to convey facts, figures, and statistics directly to the viewer in the form of text. If your documentary is trying to prove a certain argument, you may want to make use of these to relay facts that prove your argument. In our car documentary, we might want to use on-screen text to convey specific statistics about, for instance, declining membership in classic car clubs in Austin and nationwide. Use these with restraint - don't constantly bombard your audience with textual and numerical data. It can be exhausting for the audience to have to read mountains of text, so use this direct method only for the most important information. A good rule of thumb is to, whenever possible, "show, not tell."

Think music (original) as you are in production. Try to employ local musicians and musical talent in your projects. Avoid copyrighted music by creating your own. Or, you can find music on a public domain site or from a musician willing to share their talents.

Edit your film. You have all the pieces - now it's time to put them all together! Use a commercial editing program to assemble your footage into a coherent film on your computer (many computers are now sold with basic video editing software.). Remove everything that doesn't logically fit into the theme of your film - for instance, you might remove the parts of your interviews that don't directly deal with your film's topic. Take your time during the editing process - allow yourself plenty of time to get it just right. When you think you're done, sleep on it, then watch the entire film again and make any other edits you think are necessary. Remember Ernest Hemingway's thoughts on first drafts. Make your film as lean as possible, but be a reasonable and ethical editor. For instance, if, while filming, you encountered strong evidence that goes against your film's viewpoint, it's a little disingenuous to pretend it doesn't exist. Instead, modify the message of your film or, better yet, find a new counter-argument!

Testing, Marketing and Screening

Do a screening. After you've edited your film, you'll probably want to share it. After all, films were meant to be watched! Show your movie to someone you know - this can be a parent, a friend, or someone else whose opinion you trust. Then market your project as broadly as possible. Have a public screening rent, beg or borrow a venue to allow audiences to enjoy your work. Get as many people involved as possible. For every person involved in your project, it translates to two people in the audience for the screening or to buy your documentary. Send your documentary out to festivals but choose fests carefully. Pick ones that screen projects similar to yours. Be prepared to get honest feedback. Ask your viewer(s) to review your movie. Tell them not to sugarcoat it - you want to know exactly what they liked and what they didn't like. According to what they tell you, you may choose go back to editing and fix what needs to be fixed. This can potentially (but not necessarily) mean re-shooting footage or adding new scenes. Get used to rejection and toughen up. After investing countless hours in your documentary, you expect audiences to react and respond. Don't be disappointed if they aren't "over the moon" about your project; we tend live in a media-consumptive world today and audiences have high expectations and low tolerance.

Spread the word! When your film is finally exactly how you want it and as good as you think it can possibly be, it's time to show it off. Invite your friends and family over to watch the final cut and "meet the director." If you're bold, you can even upload your movie to a free streaming site (like YouTube) and share it via social media or other online means of distribution.

Take your documentary on the road. If you think you have a top notch documentary on your hands, you should try to give it a theatrical release. Often, the first place a new independent film will be screened is at a film festival. Look for festivals near where you live. Often, these will be in large cities, but some are occasionally held in smaller towns. Enter your film in a festival for a chance at getting it shown. Usually, you will have to provide a copy of your film and pay a small fee. If your film is selected out of the pool of applicants, it will be shown at the festival. Films with good "festival buzz" - that is, festival films that are particularly well-received - are sometimes bought by film distribution companies for a wider release! Film festivals also offer a chance for you to gain visibility as a director. At film festivals, directors often are asked to talk about themselves and their film in panel discussions and Q&A sessions.

Get inspired! Making a documentary can be a long, arduous process, but it can also be an immensely rewarding one. Shooting a documentary film gives you the chance to entertain and captivate an audience while simultaneously educating it. Moreover, documentaries offer filmmakers a rare chance to change the world in a very real way. A great documentary can illuminate an oft-ignored societal problem, change the way certain people and events are perceived, and even lead to changes in the way society operates. If you're having difficulty finding the motivation or inspiration to make your own documentary, consider watching and/or researching any of the influential documentaries listed below. Some of these were (and still are) seen as divisive and/or highly controversial - a good documentary film maker welcomes controversy! Zana Briski & Ross Kauffman's Born Into Brothels Steve James' Hoop Dreams Lauren Lazin's Tupac: Resurrection Morgan Spurlock's Supersize Me Errol Morris' Thin Blue Line Errol Morris' Vernon, Florida Barbara Kopple's American Dream Michael Moore's "Roger & me" Jeffrey Blitz's Spellbound Barbara Kopple's Harlan County U.S.A Les Blank's Burden of Dreams Peter Joseph's Zeitgeist: Moving Forward.

As a last word––enjoy the process. It is a creative experience and you will learn from your mistakes.

Comments

0 comment